Two days before my thirty-first birthday, I find out I’ll be losing my housing again—this year, once in January, and once in July. In an effort to celebrate anyway, I take the day to drive MT and I down to the gay nude beach bordering the cliffs at torrey pines, eating sourdough bread, fresh basil, pickles, and cheese with our fingers, sitting in the sand, swimming in the surf, communing with the ocean, my gaelic namesake. In the weeks that follow, I fill every spare gap of time between hunting craigslist for a room or apartment, and my day job designing affordable housing, with drawing minuscule, precisely-calibrated, intertwining and overlapping linework in grid formation.

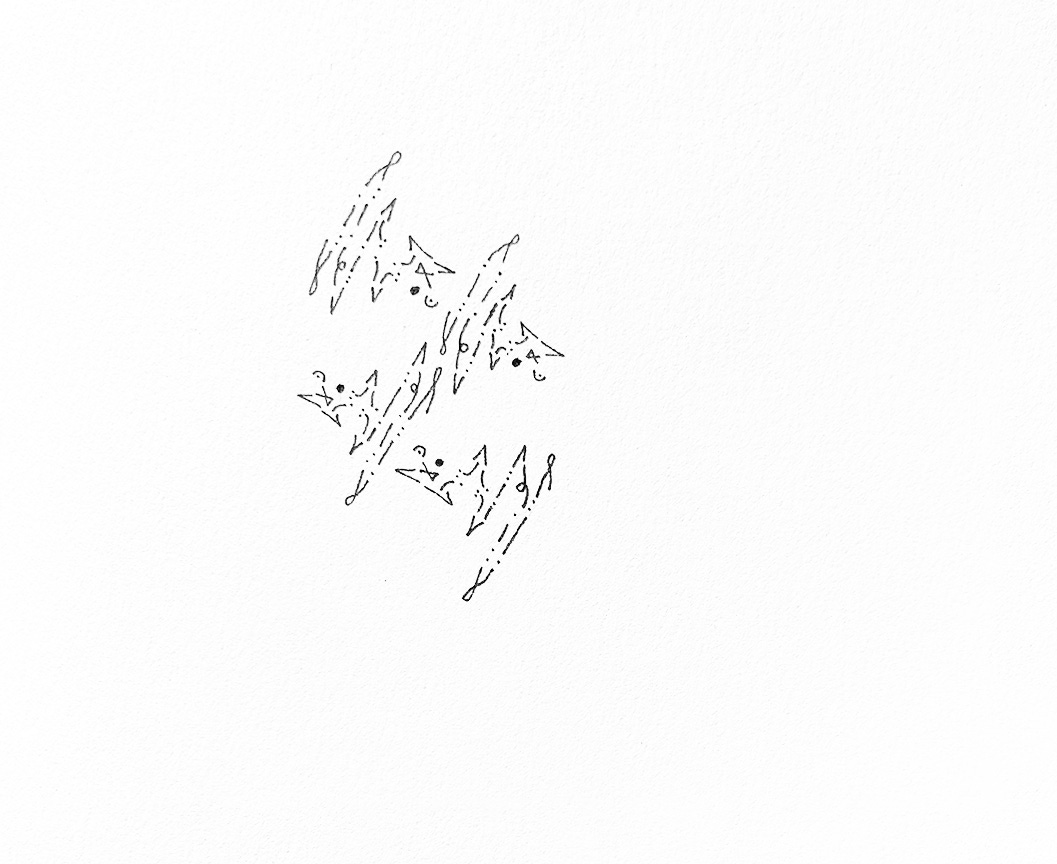

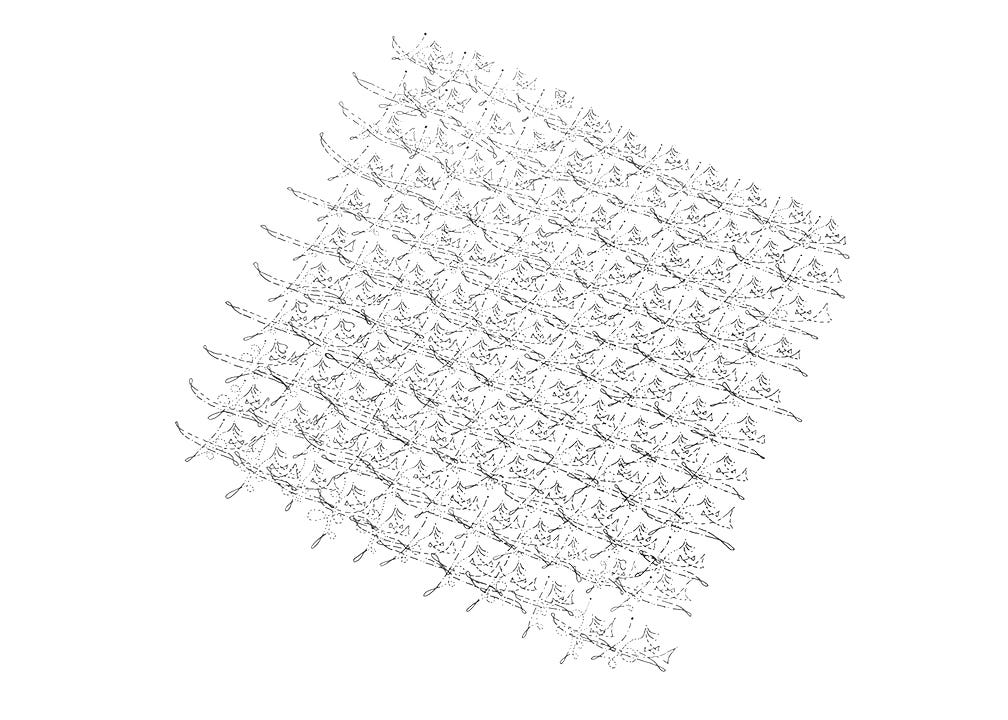

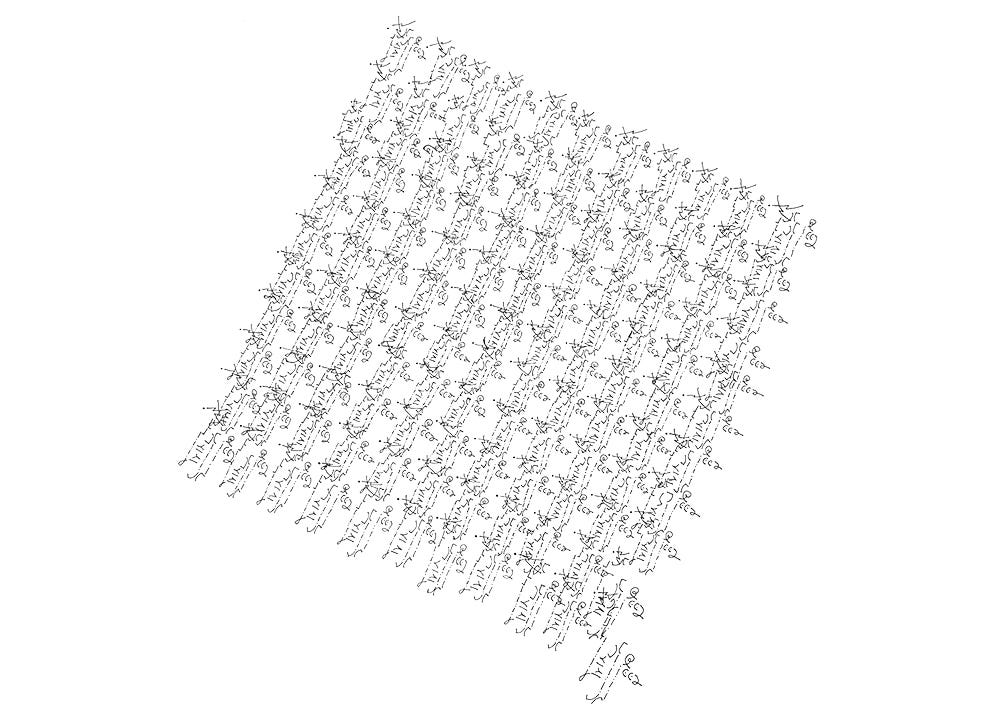

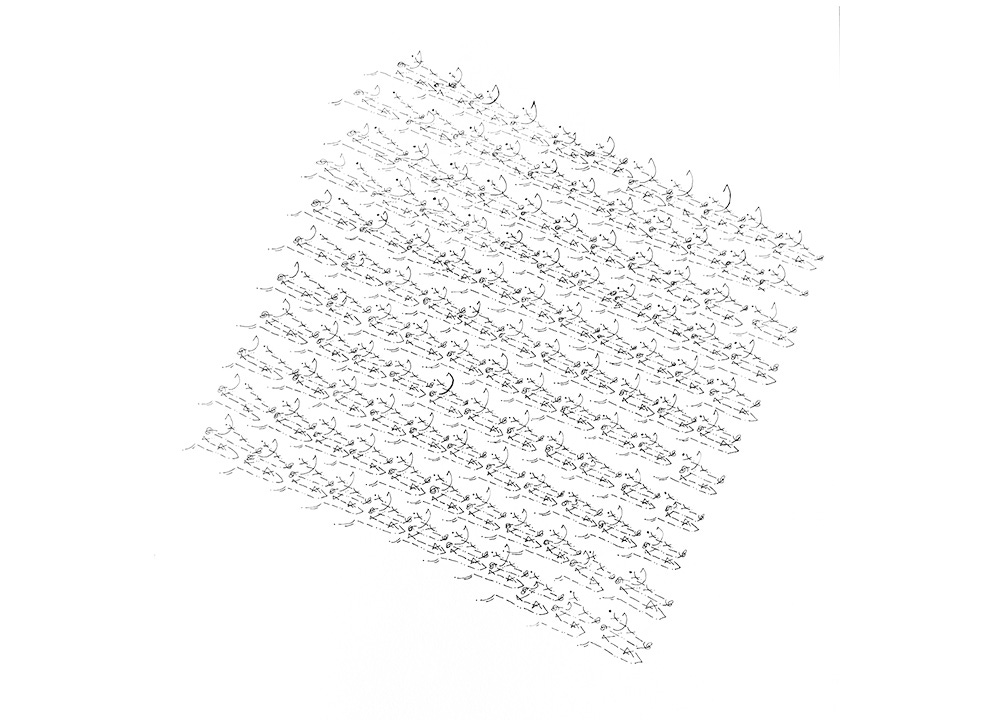

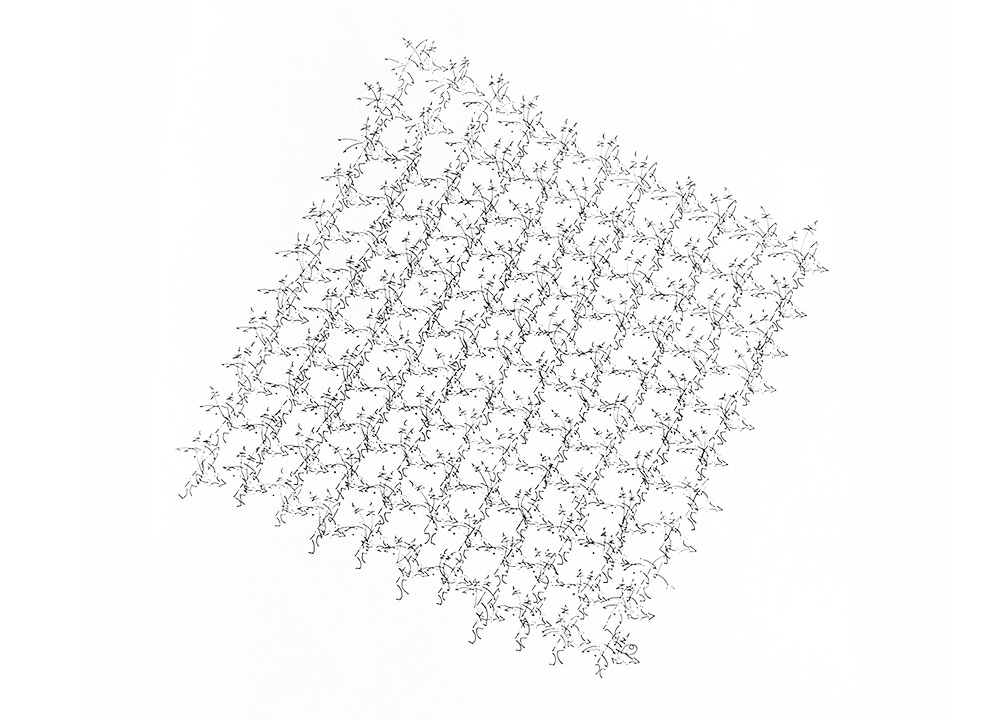

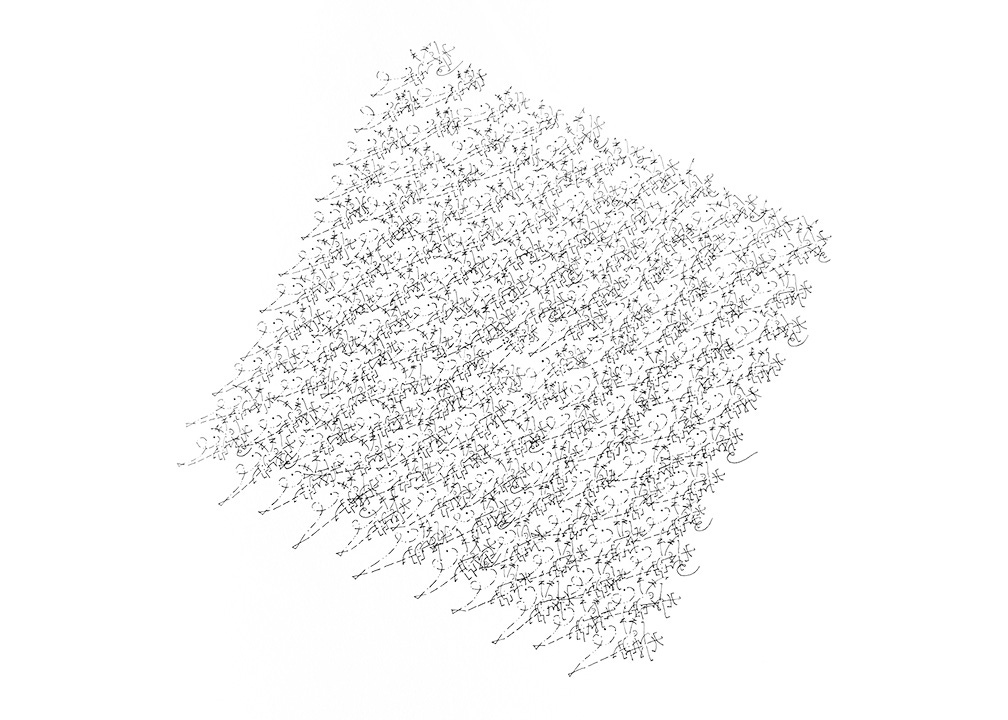

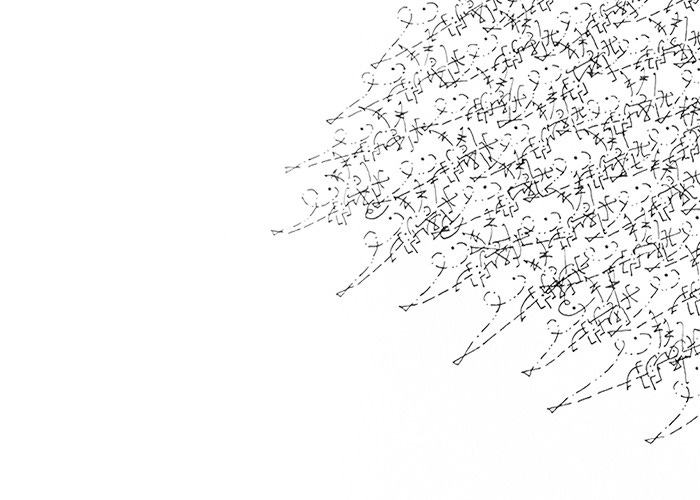

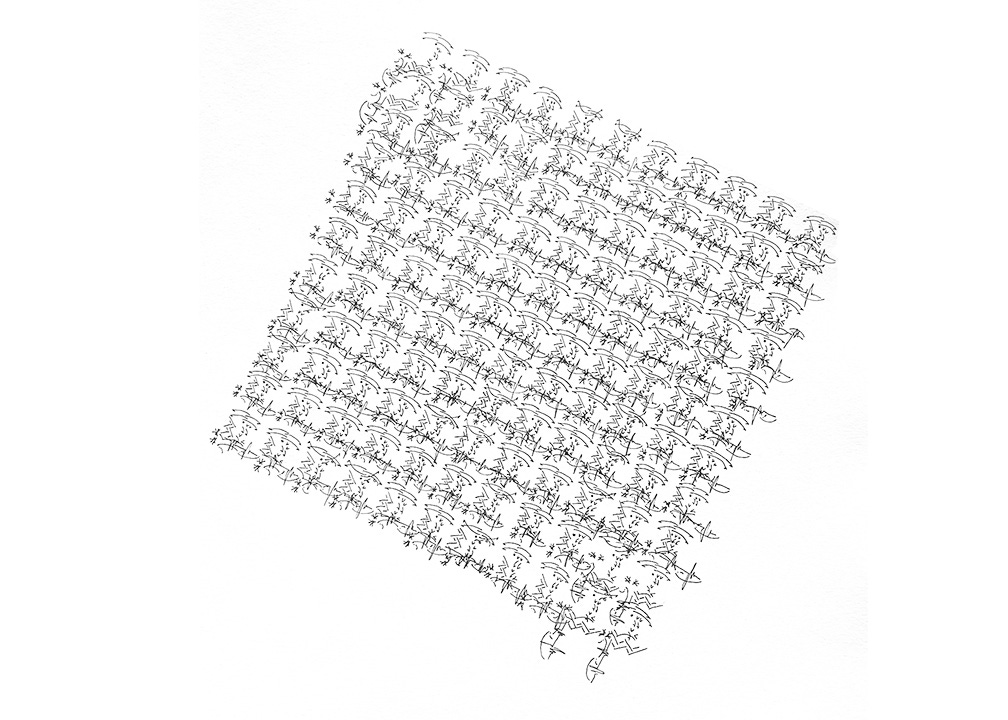

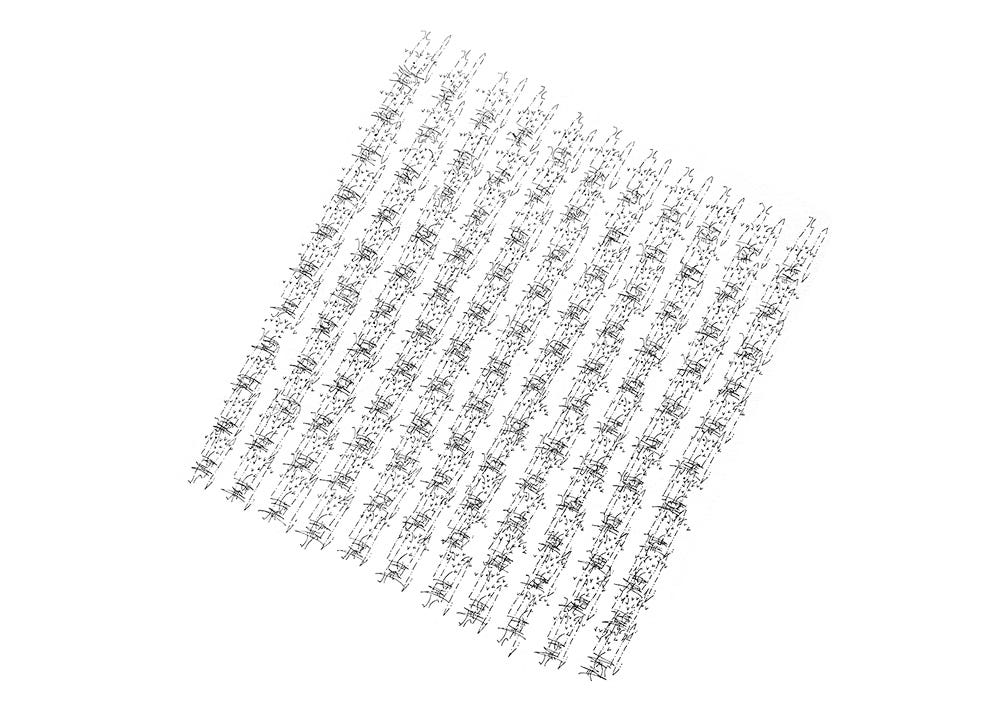

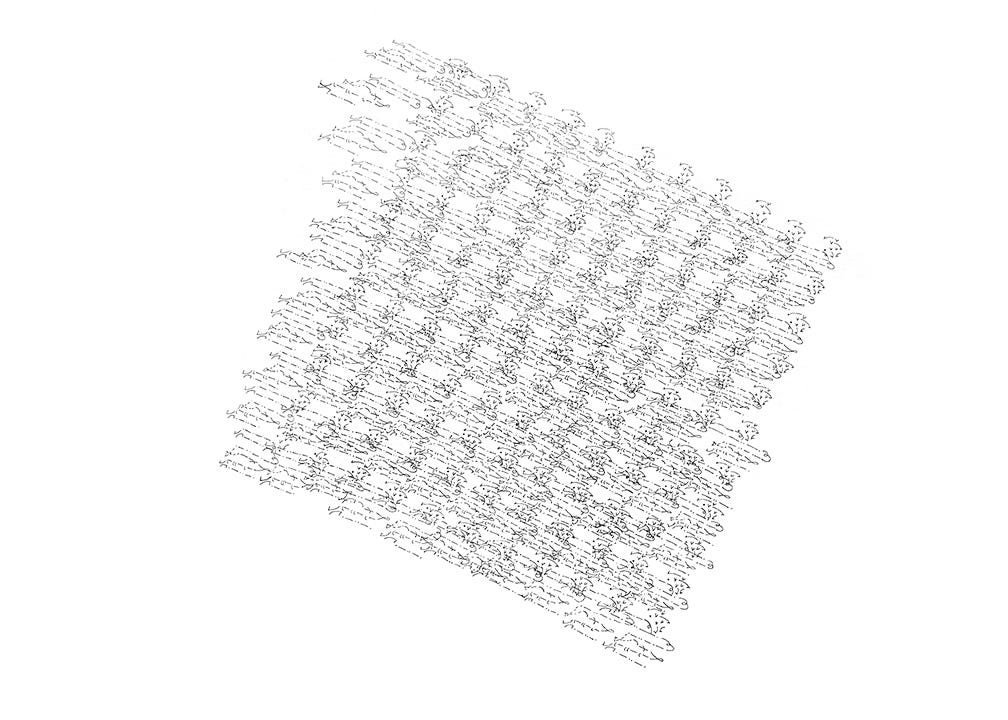

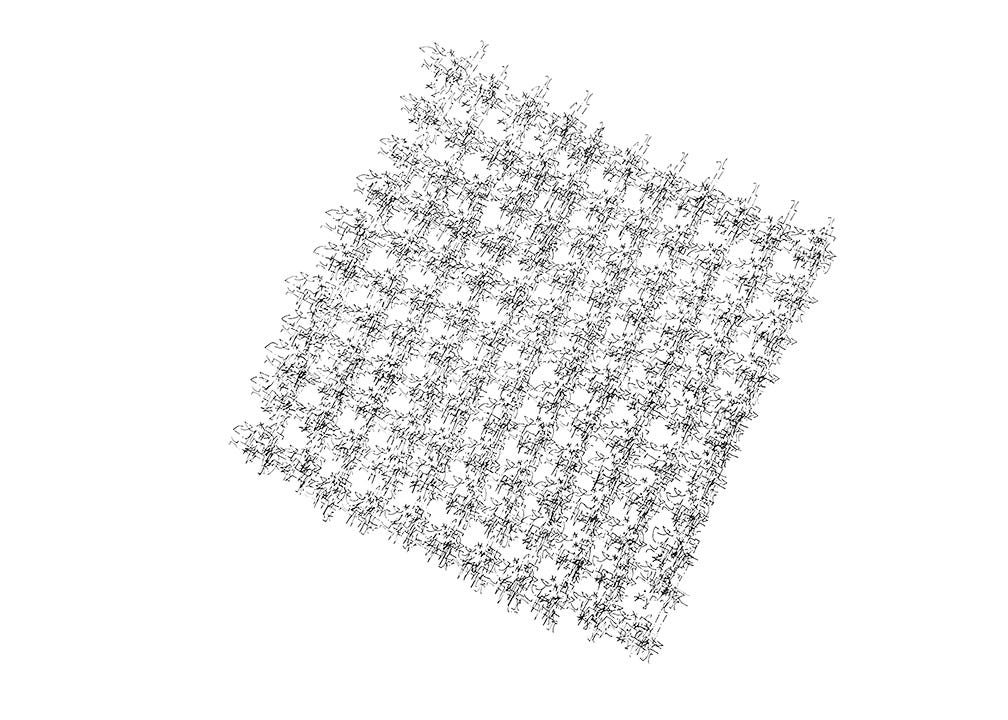

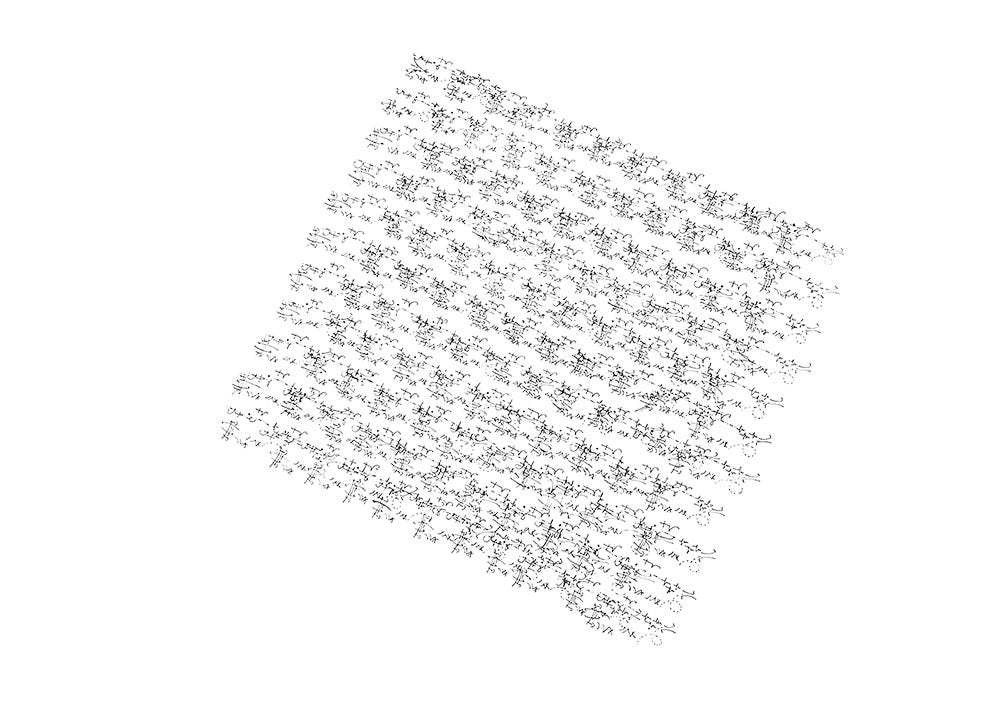

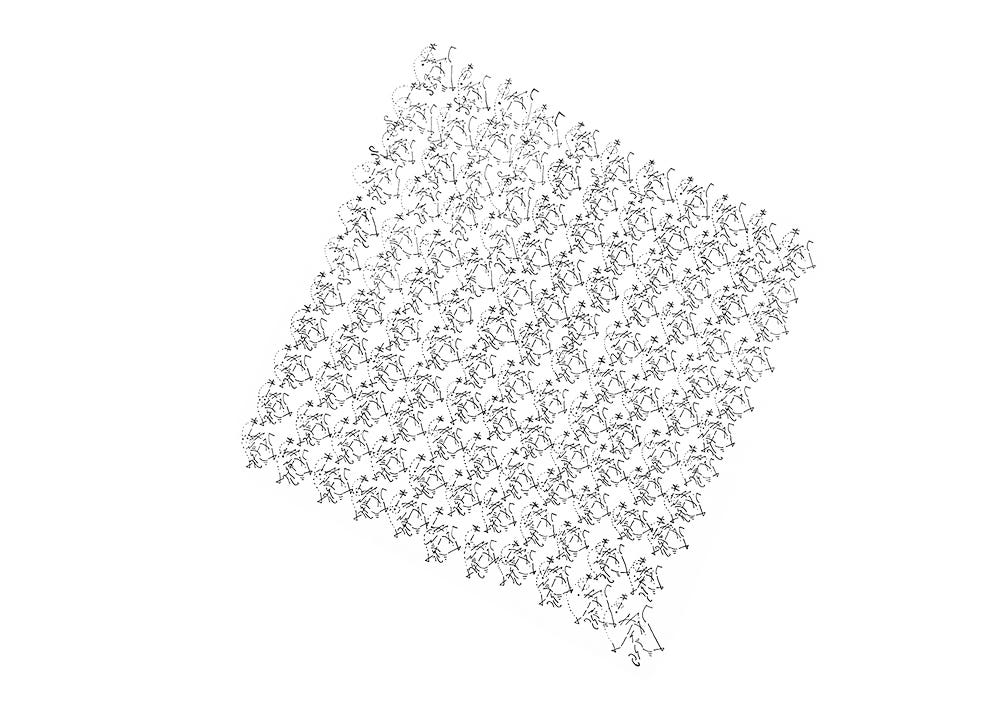

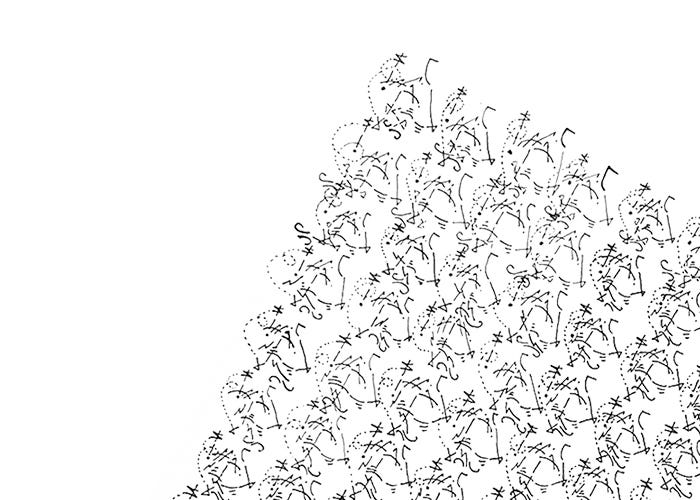

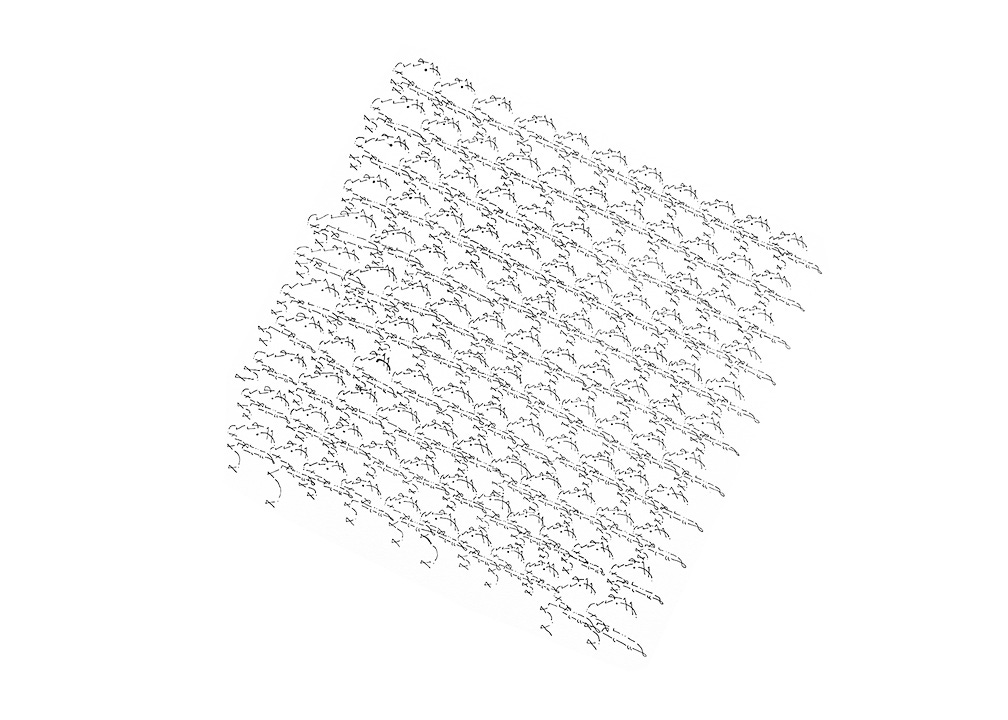

Early on, when a friend refers to the project as “abstract dance drawings,” I bristle involuntarily. Abstraction, by definition, would deal in ideas rather than events, whereas the work I’m making is literal and physical: each linetype and form corresponds precisely with a step or move, consistent across every choreography depicted, each detail representative of specific footwork and flourishes. The system I’ve constructed is a compulsively technical, structurally rigorous, exacting mechanism for depicting dance. In the listless height of summer, crammed between a housing search and working a job that pays the rent, drawing is both an avoidant tactic and a meditative salve against ambient precarity. These drawings depict fifteen of the hundreds of line dances that I’ve committed myself to memorizing in four-hour nights of nonstop dancing, twice a week, for almost two years now.

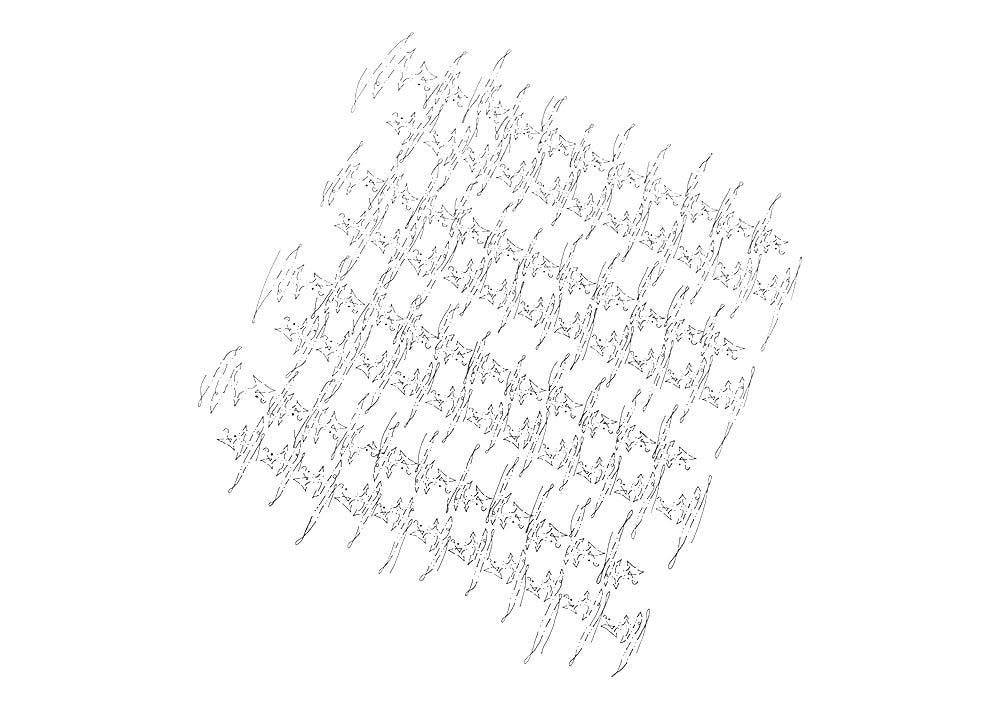

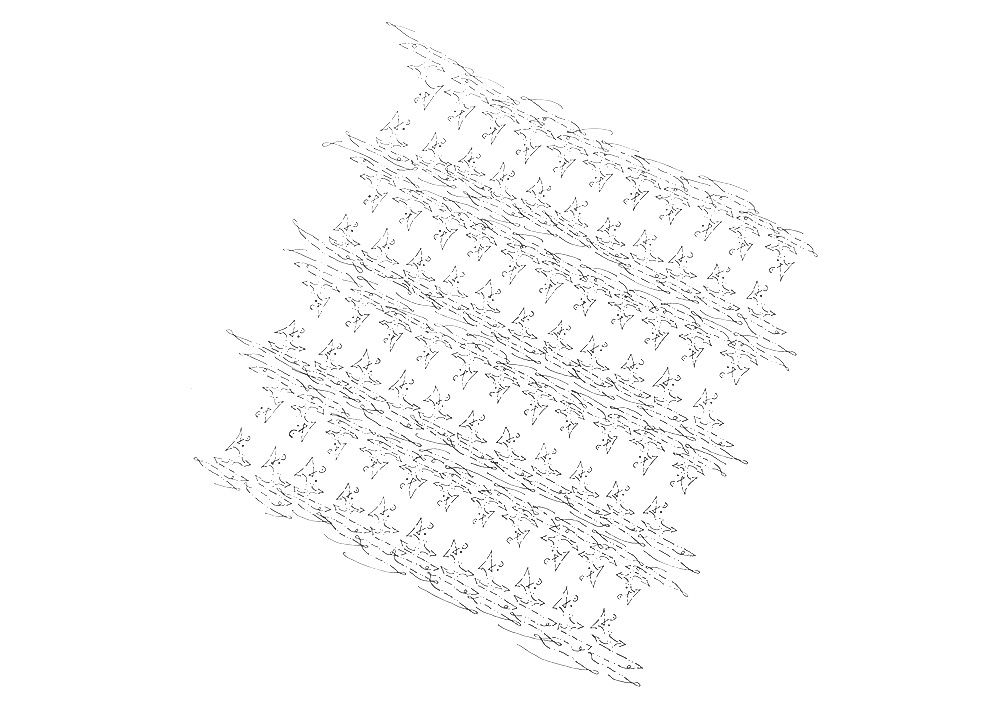

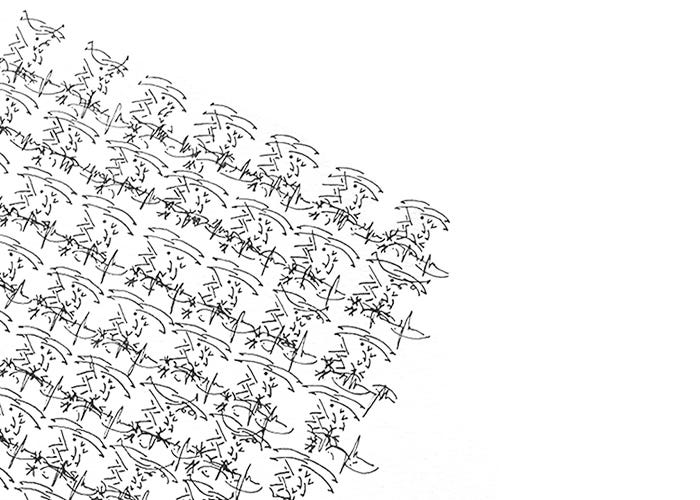

Dancing in the line, in the school of fish, the structure of the grid is a stable form to push back against, a productive constraint. The muscle memory of relatively simple choreography reminds me of ten years playing the violin or fifteen years swimming competitively in my adolescence. These are frameworks within which it is easy to play, to lose myself within a given structure, directed by my physical body. I note every flourish, additional spin, improvisational footwork, or unexpected modification made by the folks dancing right next to me or across the room, fine-tuning my attention to the habits and idiosyncrasies of our little cohort of regulars—the movement of our wrists, outstretched arms, swinging hips, limbs following in the wake of our cowboy boots, a decidedly familiar cadence to me now.

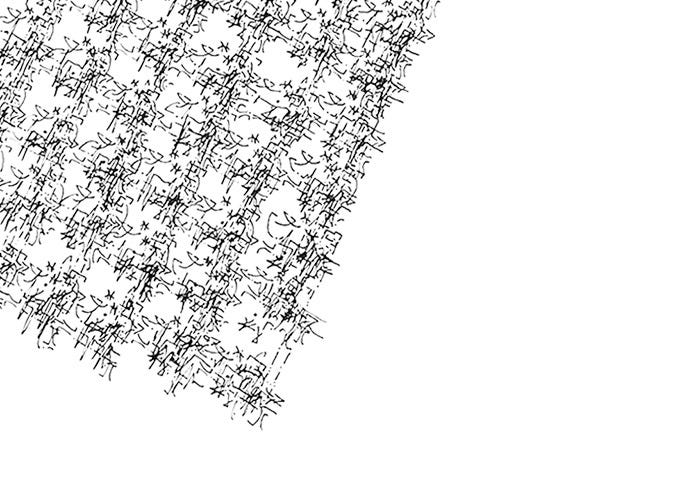

Drawing by hand, depicting these differences invariably disrupts the precision of the grid, the dissolution of sameness most visible in the fraying and fragmenting edges. Lately, I’ve been preoccupied thinking about coordinated movement and bridging across difference, in the midst of worsening economic inequality and an increasingly severe housing and mental health crisis, on a rapidly warming planet, witnessing an ongoing genocide funded by our tax dollars here in the u.s. I don’t mean it as an overwrought and contrived metaphor, but drawing intricate grids that produce simultaneity through variation leaves a lot of time for thinking about organizing on the left, reflecting on the encampments and the community groups that came together there last spring, meditating on the value of third place—communal public realms, absent a fee for entry—where rhythmic and repetitive meeting builds solidarity through neighborly behaviors, shared food, and shared resources.