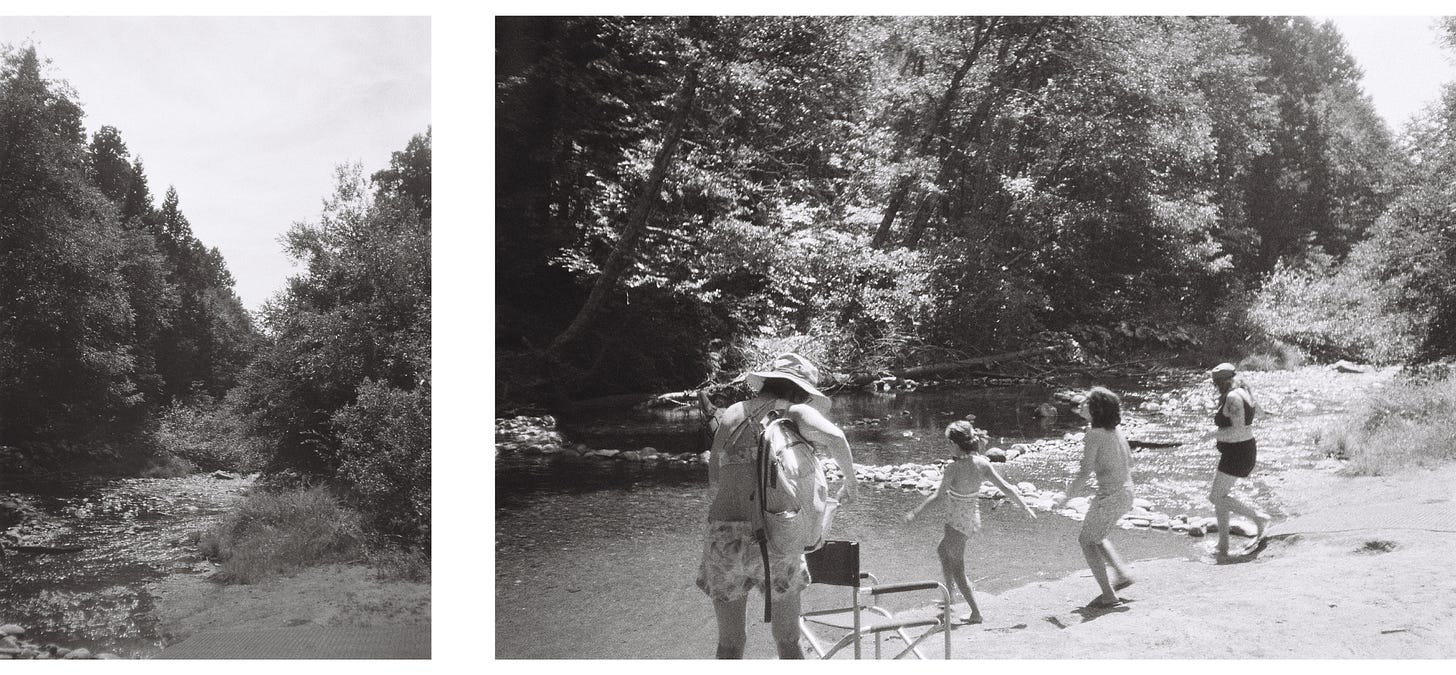

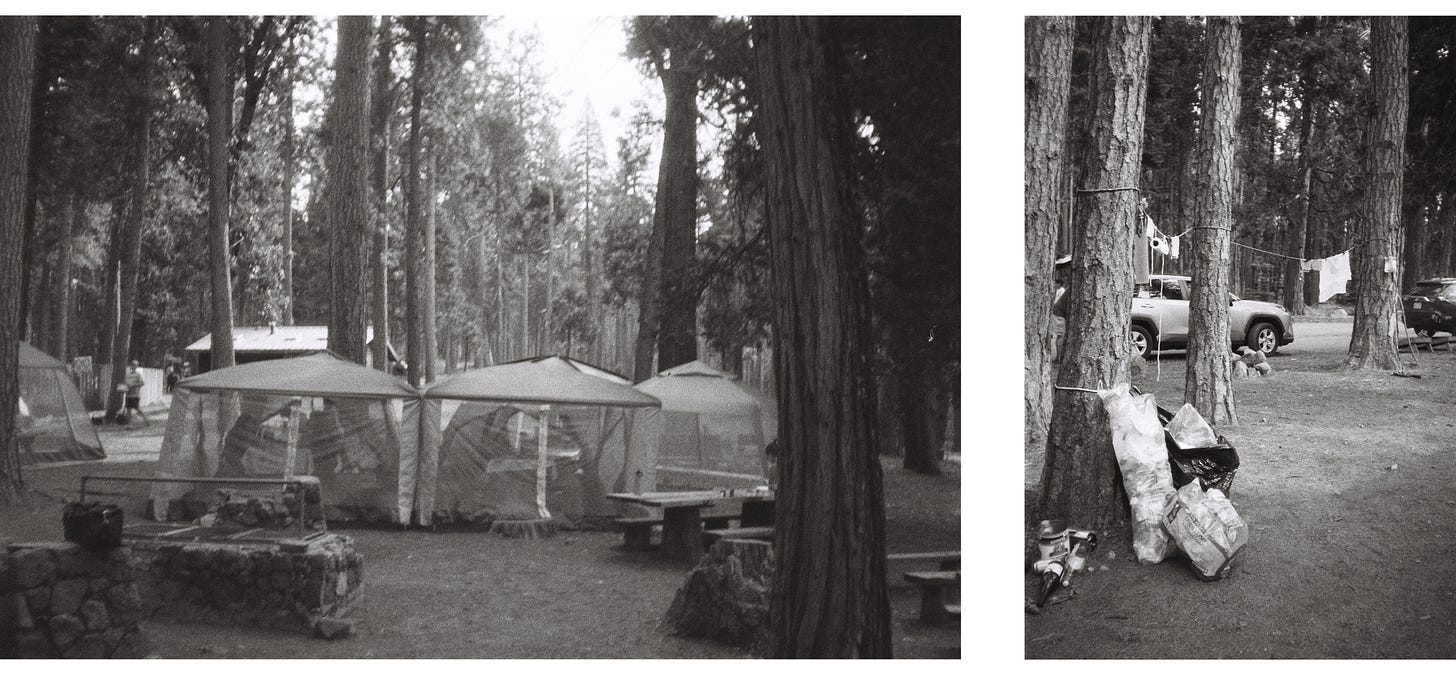

I pull up at our regular campsite this year a little cranky and a little hungry after driving the distance from LA straight through, awake since 430am. Everybody wants to go to the creek. My uncle asks for a ride on behalf of my aunt and oldest cousin, along with another niece from camp who I haven’t met yet. I can almost feel the ugly and small parts of my body, conditioned by the selfish individualism promoted by capitalist mythologizing, resisting this statement of collective desire, unwilling to accommodate anything but my own self-directed whim. But of course — it’s better this way. I pitch the tent quickly with EK, MT grabs a swimsuit, another car arrives with family who’ve just flown in from Nashville and LA, and we all trundle off toward the creek together, caravanning along the winding mountain road under the sequoias that, if you follow for long enough, turns from a two-lane highway into a treacherous-seeming single-lane road with cars driving in both directions.

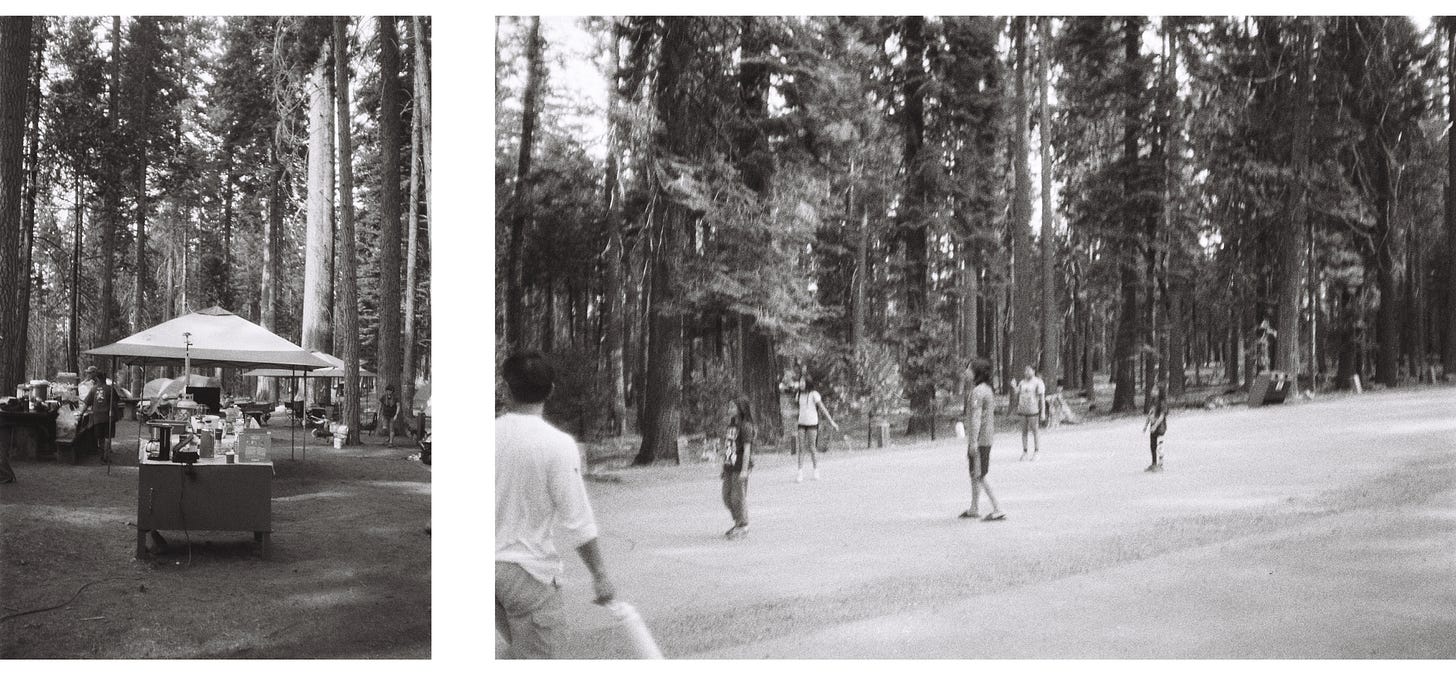

Everything is communal isn’t just aspirational here; it’s practiced. We construct a temporary place that runs on what we believe we owe to each other. Toban 当番, meaning “person on duty” or “being on duty,” is the organizational structure by which we delegate tasking. As a word, “toban” has carried a sense of home for me since before I fully conceived of discrete language, but I still need an internet search engine to tell me that the kanji for this word is 当 hit, and 番 number, or turn. The turns that we take rotate by the day, but the tasking itself rotates by the years that we’re alive. Toddlers and young kids take a wet rag and wipe down the laminated tablecloths after big communal meals. Teens gather at the bathroom sink to wash dishes after dinner. Names marked in red have seniority at camp, and years of trust behind their fried rice breakfasts, cleaning up our leftovers by topping them with soy sauce and chopped scallions, pans of eggs and tater tots with slices of cheese draped over top sizzling on the camp grill. The names in red provide hierarchy and leadership to cooking and cleaning toban crews, executing creative decision making for an unexpected mix of ingredients, or coming up with solutions to unclog the blocked sink drain late at night.

Driving east to Stanislaus forest from the Oakland hills, auntie P has been organizing this operation for three decades at the same campsite. I’ve heard the story many times over the past twenty years, but I’m never able to enumerate the precise details of its inception and cannot be held accountable for the accuracy of my loosely-sketched retelling here; it was before I was born. Basically, auntie P’s group of college friends and her Buddhist temple in Berkeley each held annual camping trips for which she would largely take on the work of organizing and orchestrating, and eventually she collapsed the two into one big trip. My dad’s second-eldest sister was brought into the fold, and that’s how they wound up with all of us.

The chaotic amalgamation of longtime chosen family and biological family constructs a specific type of closeness in this temporary place that I invariably struggle to articulate — although whenever I talk with friends who grew up in organized religion or other cult scenarios, I find traces of this quality. There is always a spat happening between lovers or longtime partners; someone’s niece or nephew with an emergent need; pairs or trios of preteen cousins getting into mischief and requiring loose supervision or perfunctory caretaking; an auntie or uncle with a sympathetic ear when you’ve had a fight with a girlfriend, brother, cousin, or parent; a peer hanging around who is bored enough to play a game or make trouble with you.

The disordered chaos of our individuated family dynamics is made temporarily public and porous to each other in this place, itself a kind of public domesticity. We can be oppositional in our views, brusque or impatient in a given interaction, and maintain our temporary commitments to each other, participate in toban side by side, face the world the same way. At camp, the trust is built out between us over the years of shared bugspray and shared childcare, late night games and stargazing in the clearing, the coordination of carpools and cooking tasks. I draw out a throughline between this interwoven set of family dynamics and the temporary place it constructs between us, and the ‘public domesticity’ I’m often describing in dispatches of this newsletter.

Looking across the street from my front porch, I see an upholstered office chair on rollers that’s been sitting for days on the grassy median under the sign for the bus stop, a misplaced symbol of interiority where a person waits for something as public as a city bus. Two doors down, three armchairs with floral fabrics are positioned in the front yard to facilitate interaction with the street, suggesting conversation with neighbors and passersby. I choose to read the furniture and paraphernalia of city dwellers left curbside that I’m always noticing from the bikelane as a poetic symbol or potent indicator of the private made public. One of camp’s most characteristic features is the enormous rice cooker plugged into the outlet of the camp bathroom, cord snaking out from under the wooden door, an outsized kitchen appliance sitting on the forest floor, enough rice to feed the forty to sixty of us at camp on any given day.

After dinner friday night, we stand around the camp stove carrying out SG and CE’s tradition of late night juk, a slow-cooked rice porridge that uses up the bones and broth of turkey dinner. The pot is bigger than my entire torso, enough to feed all of us gathered in the main tents, sitting around the fire, setting up another round of mahjong, getting competitive over bingo cards moving toward a blackout round. An auntie chops cilantro and scallions, searches the coolers stacked high in the uhaul for chili oil and condiments. My cousin TV and I eat vegetarian but are selectively cooperative in our consumption here, eating communally for the sake of a nostalgic family meal designed to use up all the leftover parts of an animal’s body, stretching nutrients with rice and water. We’re chatting with cousins the generation only mid-way up from us, five to ten years older, MC stirring the pot while her sister JS characteristically spills the tea — did you hear, we aren’t going to the lake tomorrow?

It’s broadly understood that earlier in the week, there are a variety of activities that people might get up to: sit under the sugarpines at the campsite, walk under the enormous sequoias at the base of camp, drive out to any of the watering holes or hikes in the forest. There are golf ranges and wineries that I recall being shocked to learn about in my late teens; I’d never noticed that aunties, uncles, and cousins had frequented these locales while I was elsewhere. We splinter off into amalgamations, regularly recombining, trusting that the mix of folks will maintain enough attention and care for the littlest ones. There’s a lack of fixity to the form of this place, a distinctly choose-your-own-adventure quality, the freedom to just be.

Later in the week, thursday and friday, there’s more of an attempt to coalesce the entire group. As kids, ‘caves day’ and ‘lake day’ meant piling into minivans vying for the most desirable carpool, wanting to be the first in the water, trying to ride with cool older cousins to avoid any parent who might have reason to reprimand us. We fill inner tubes with air in the parking lot before hiking down to the caves, carrying them on our shoulders, and the strongest swimmers ferry our sandwiches, the youngest kids, and elders across the water through the dark caverns to the dappled daylight at the north end of the creek. At the lake, we hike down to the shore carrying towels, grills, tent canopies, chairs, stacks of board games, and coolers filled with cheese, pickles, beer, and burger patties.

Both days are more involved, “more of a schlep.” The alternative lake idea this year is known colloquially as the ‘ace hardware lake,’ which tells you everything you need to know about that place. In our lexicon, it’s named simply for the corporate retailer at the turn-off from town [pejorative]. The ace hardware lake offers convenience and proximity without the expansiveness and enormity of our usual lake, down a winding forty-five minutes of road framed out by giant sequoias and regular burn patches, trees rustling in anticipation of the day, all of us jittery from several camp cups of coffee. Or on the drive back, a wind rushing in through the windows to lull us to sleep in the backseat, baked by the sun stretching into late afternoon, ears popping at the drop in altitude, a nap before we all rally back together to cook communally, play increasingly competitive board games, and dance late into the night.

JS and MC agree that I should talk to auntie P about the lake, and subsequently I get their dad, auntie P’s brother, to talk to her, who then recruits uncle A. TV laughs that this is “a full-on political campaign.” There’s levity to this jostling around camp’s group activity, an underlying respect for anyone who’s done the bulk of the organizing work here for years, and an understanding that we all participate in constructing this temporary place. JS institutes the “medicare rule:” nobody over the age of 60, wait, make that 65, because some of your uncles and dads in their early 60s are extremely physically capable, has to carry anything down to the lakeshore. The ‘kids,’ all of us well-into our 30s, will handle the kayak and canoe rentals, the barbecue, and the early morning drive out to claim a spot on the beach that can accommodate all sixty campers straggling to meet us within the hour, young kids in tow.

It’s funny to navigate these roads as a driver after so many years as a passenger. A lot of the kids drop off in their mid- to late-twenties, moving away from California and away from family, busy with the bureaucracy of living and making a place for themselves. I haven’t been to camp for more than half a decade when I come back this year, my own hiatus of precisely this kind. Driving MT and I up the 99, I fully anticipate that I won’t see any of the young kids I most remember, all of them now in their twenties, little T and little K and little E who would trail after me all over camp and at the lake, following me through the caves and up the creek, giving me a sense of purpose and usefulness that I hadn’t yet earned as a young person, but that I was afforded the privilege of practicing all week.

This year at the lake I’m off on my own, sunning on a small, submerged rock partway across the water. From shore, I appear to be sitting on the lake surface. Two cousins swim up to me, giggling shyly to each other, looking up at me bemusedly, and ask if I’ll swim them across to the far side of the lake. Nono, not the actual far side, just that big rock at the center, we can see it from here, will I lifeguard them across? Dogpaddling through the icy shallows, they tell me they’re afraid of snakes, mention in hushed tones about the boys at camp, tell me about their moms, one of whom doesn’t like to come camping, and what they’ve deduced about the character and personality of a person who doesn’t like to camp. An unceasing stream of ideas erupts from their mouths, punctuated with exclamations of excitement and indignation, while we lie on that big rock in the sun.

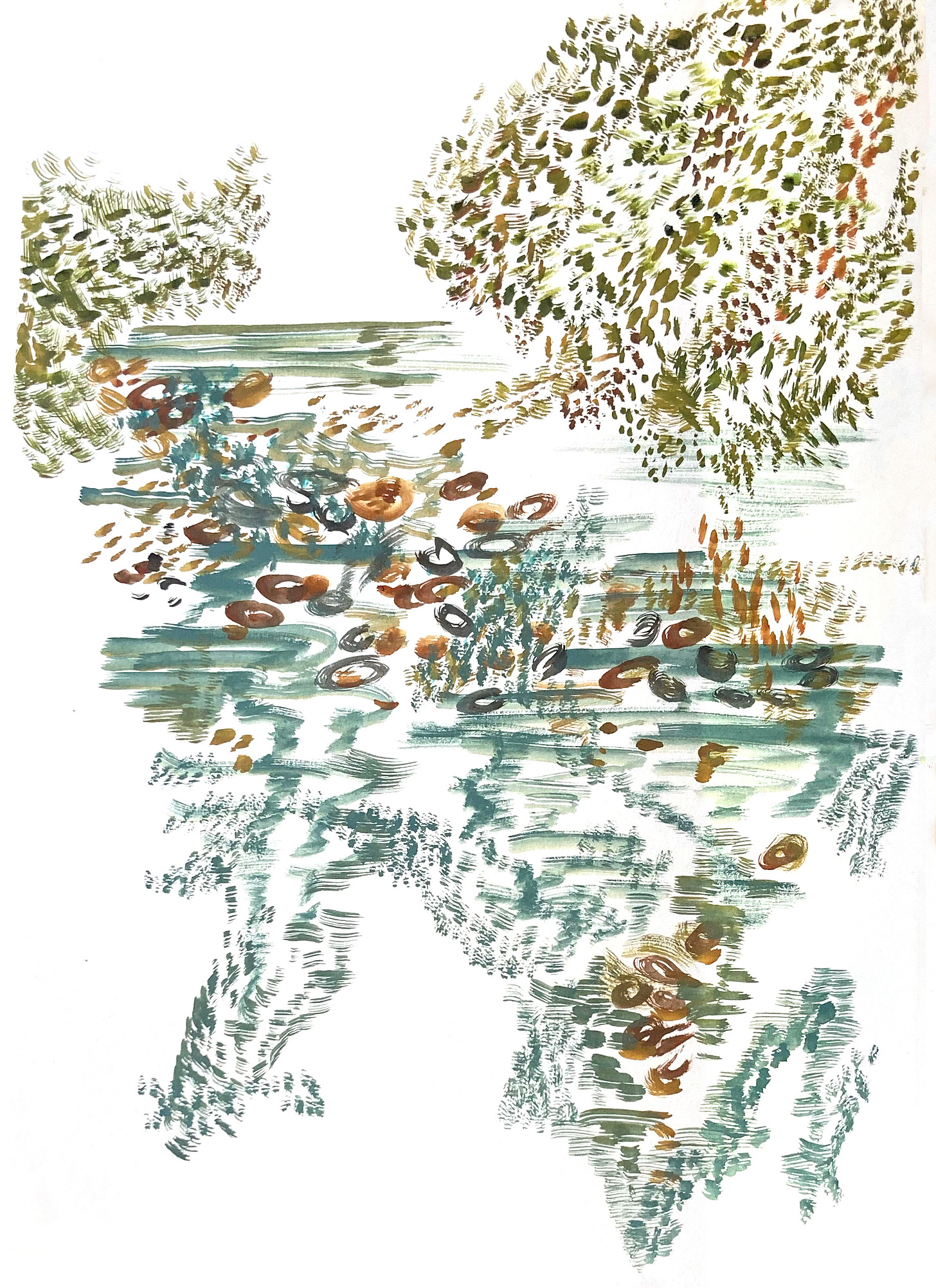

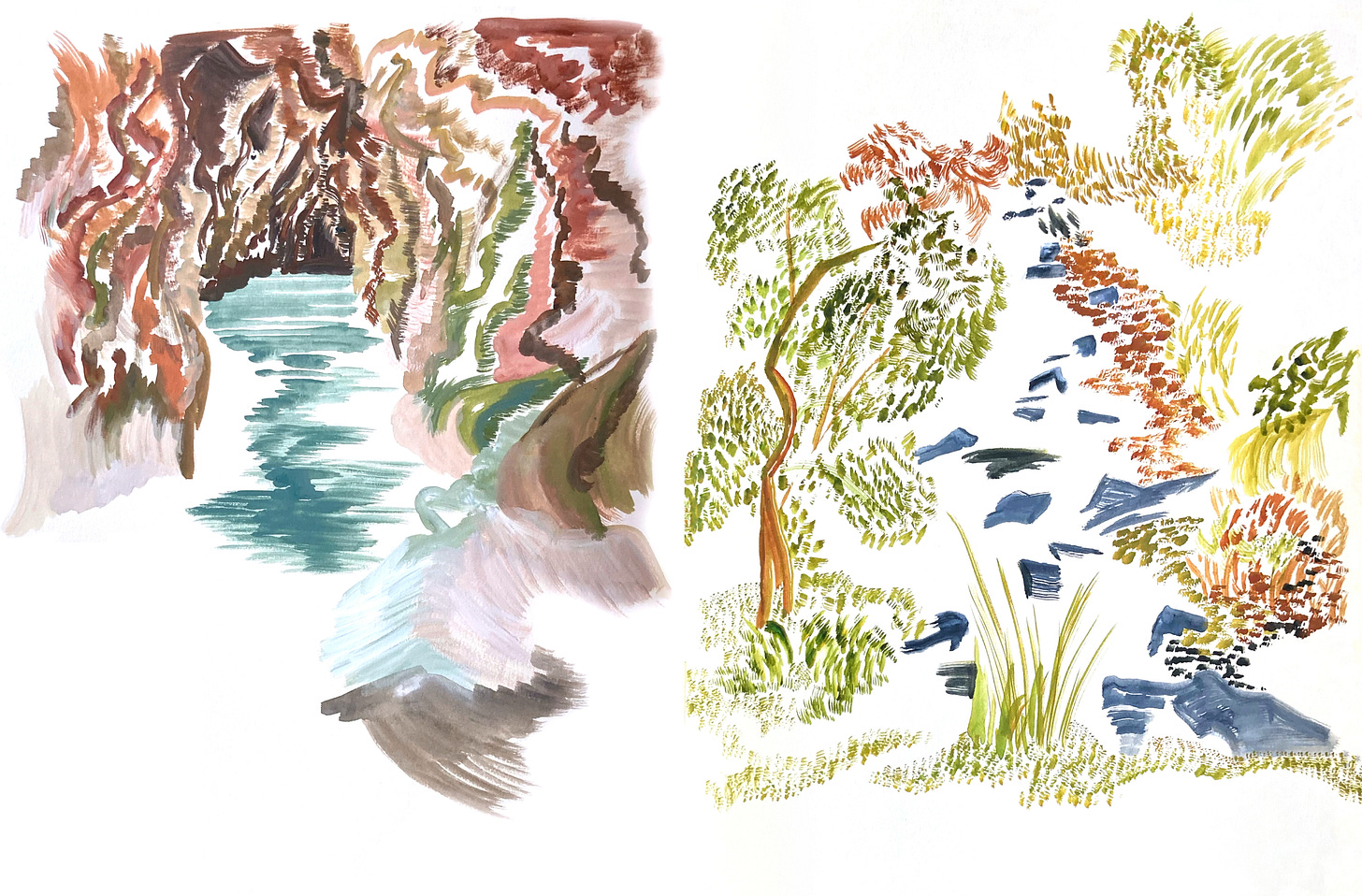

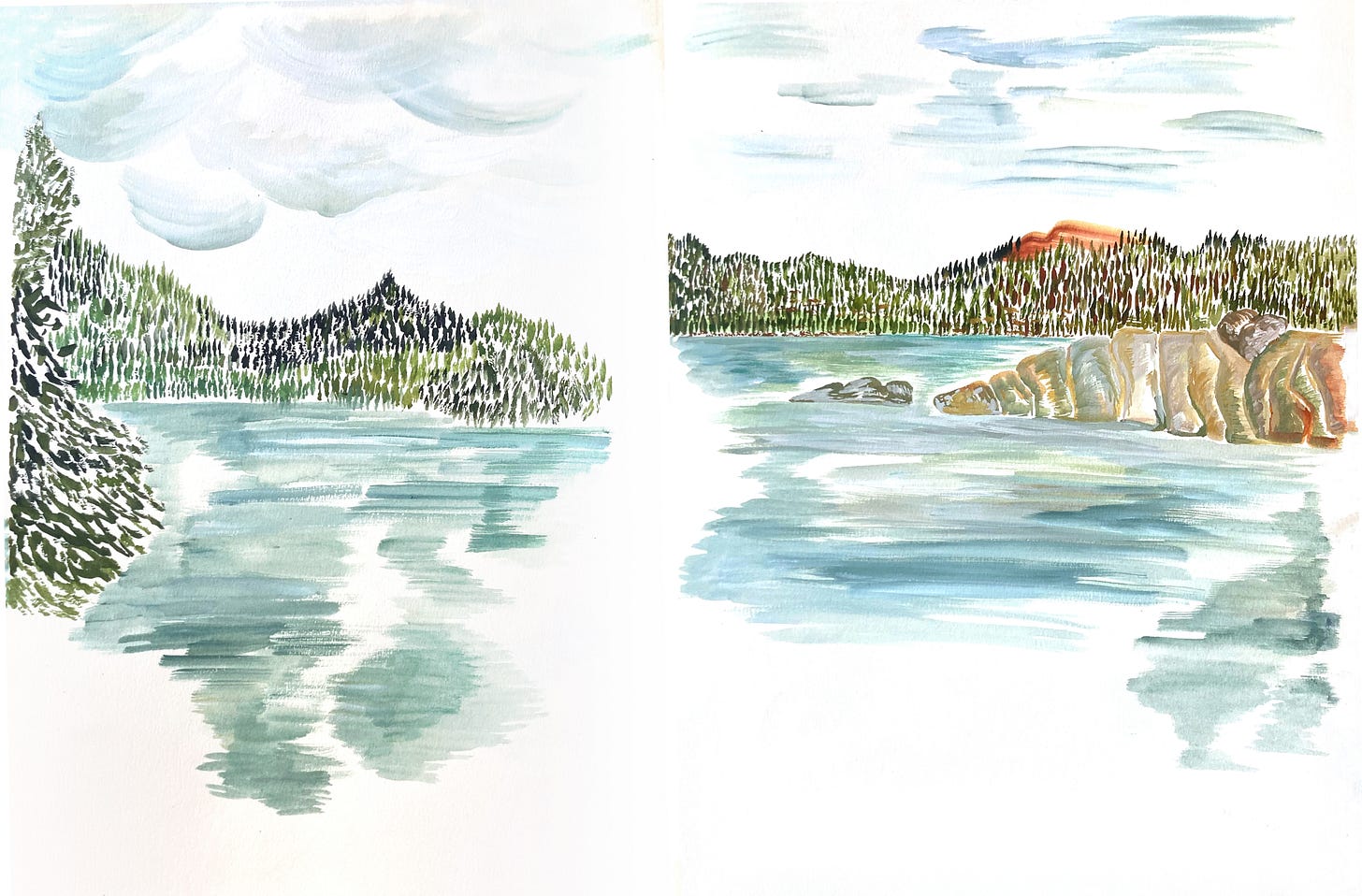

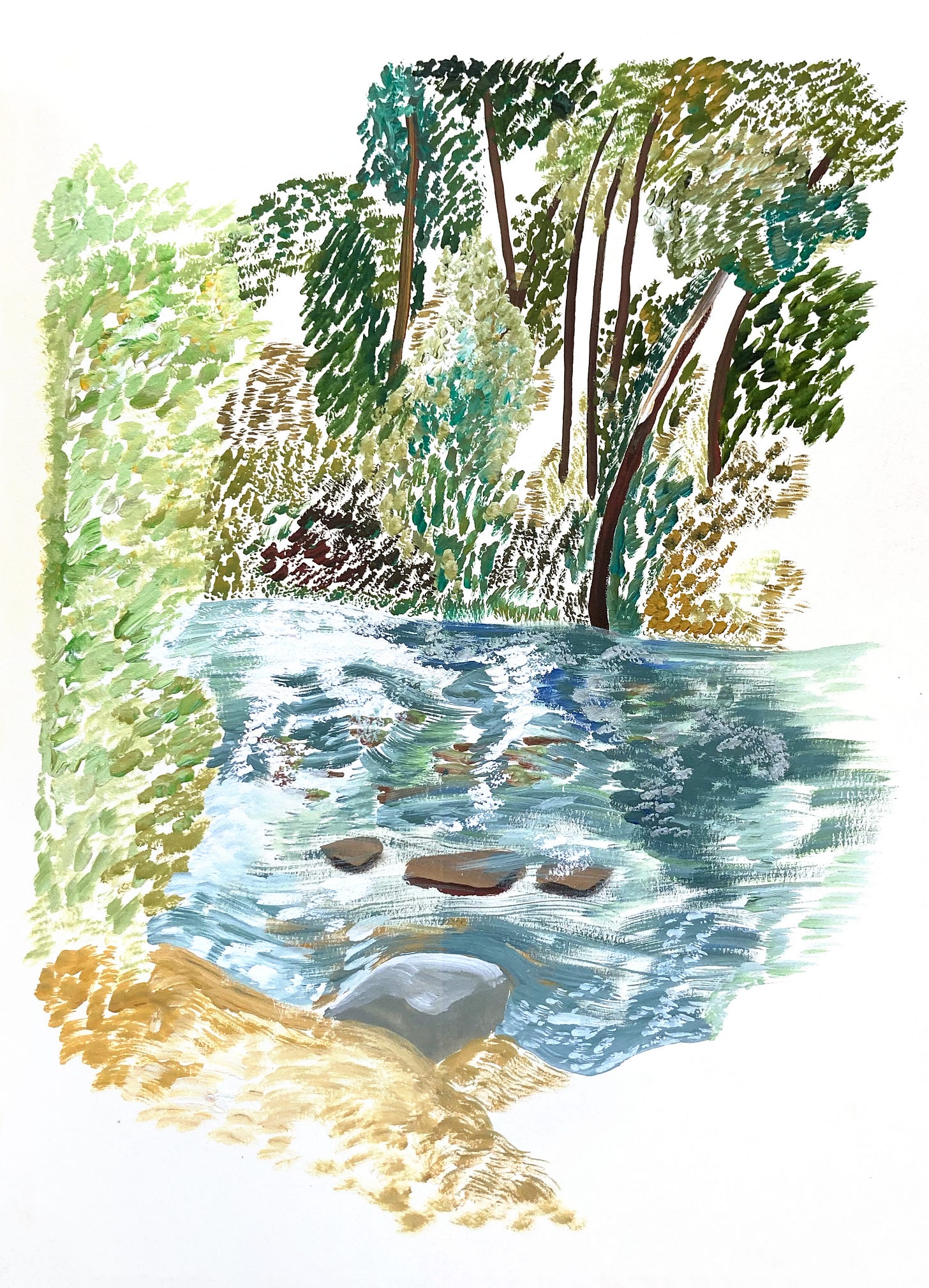

Back on the shore watching uncle MY splashing around in the shallows, I tell auntie WM that’s the moment I feel I am properly back at camp. Even as the kids age, tire of this tradition and come back to it, in cycles, there’s an opportunity to show up for the young people here. The next morning, one of the younger girls who I’d last seen at camp when she was a tiny baby comes trailing after me. She’s been fascinated by our drawings and paintings all week, and has shown us some of her own, sitting next to us on the wide wooden benches in the afternoons. Pre-coffee and bleary-eyed, I’m brushing my teeth at the big plastic sink basin when she asks after my girlfriend, “Where’s MT?” The question isn’t urgent but is earnest, and delivered with assertive and exacting directness. Later, MT tells me that all she had wanted to do was bound over and say, “Good morning, MT!”

In the existential heat of a sunday afternoon in late august, brushed by the faintest early fall breeze through the back screen door, J, BX, and I get into extended conversational musings about the possibilities and pitfalls of raising children relative to maintaining an art practice under the constraints of capitalism; the conventions of the nuclear family versus prioritizing broader community; the divide we see between our peers with versus without children these days; the challenges to cultivating deeply fortifying intergenerational friendship; the invisibilized maintenance and reproductive labor largely unspoken but typically expected of people socialized female; the unknowable inspiration that we observe in artists whose work we admire that is partially motivated by their children and by their own work as parents.

We describe the most compelling cases in the unconventional arrangements of our friends and acquaintances, but in every instance financial feasibility seems to outweigh even the most sharply challenging interpersonal or logistical dynamics as the deciding factor in how people raise children. It’s too costly to stay centrally located in the city, reliant on peers and broader communal networks, when the alternative is the intergenerational living built into moving back in with one’s parents. Relying solely on nuclear family structures invariably leads to isolation.

We imagine what it could look like for our own neighborly behaviors, biking to each other’s houses for a late-night snack or mid-afternoon meal, lying on the carpet staring at the ceiling together after work, spontaneously meeting up to collage and paint in each other’s living rooms, reading aloud to each other in the garden, to extend to offering childcare to our friends, keeping them in our orbit. For J, BX, and I, this conversation is largely hypothetical. We’re only just starting to know a few peers in our creative communities with young kids. If our preoccupations are centered on the financial feasibility of our respective art practices, on the financial feasibility of participating in the rearing of the next generation, there is no opportunity for us to just exist as human animals, inspired to make art without having to capitalize on it and derive a living off it, investing adequate time and energy into maintaining broader networks of care.

The temporary commitments of camp are one way that I tether myself to interdependence, building mutual reliance into the turns of my days and years. The durational quality of camp makes this practice both manageable and imaginable for me, an incremental exertion that changes me not just throughout that one week every year, but in the wake of that week all year. Where everything is communal, everything is romantic. I can see it in the mahjong tiles laid out on dusty card tables set up in the dirt, in the woods and under the stars with aunties and uncles who have known decades of my past selves, still here, under the sugarpines.

Thanks for that and the beautiful watercolors. Makes me want to join you next time!