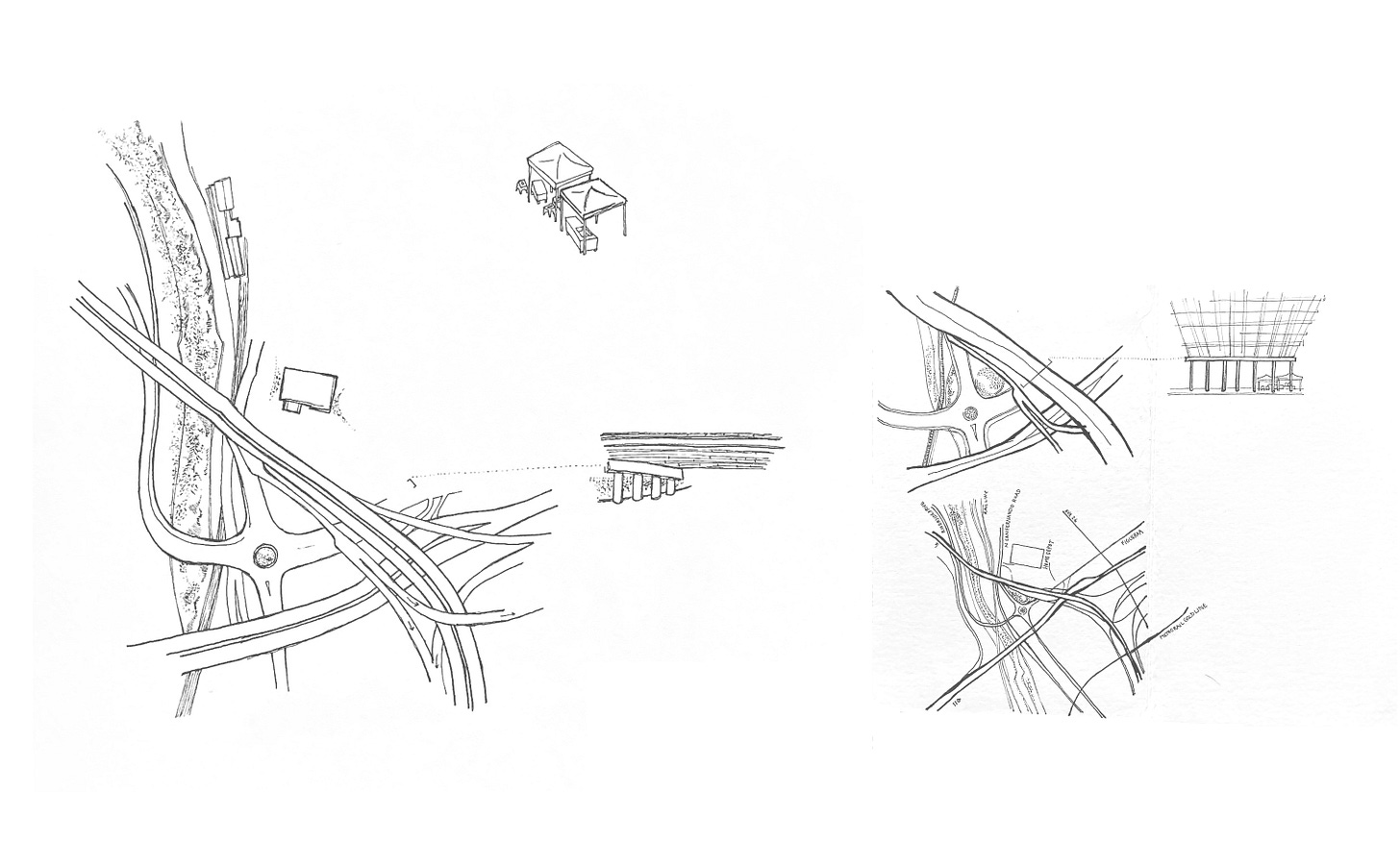

On a morning in late october, BX and I are biking back on the river, the dry breath of the Santa Anas combing through our hair, leaving it laced with static and standing on end, lips chapped, the hot, astringent smell of fire burning our eyes and stinging at the back of our throats. Underneath the tangled knot of the 5 and 110 freeways, where the river and amtrak rail lines intersect with the metro, enormous speakers bellow the word of god outwards and upwards for the sunday service gathered in the home depot parking lot. White plastic folding chairs form neat, gridded, temporary lines, studded with taco stands and their red and white checkered tablecloths, tiny multi-colored plastic stools, and enormous pots filled with beans and stewed meat.

The service echoes across the river, conspicuously loud today, the unrelenting exhortation to love and devotion to god intelligible to me even as a non Spanish speaker. Erranding and commuting everywhere by bike, I observe near-constant activity occupying the underside of this freeway. Early mornings, construction workers and laborers pull up in their trucks, passing the woman at the corner with her small beach umbrella and plastic bins of pan dulce, and that guy who is always selling cowboy boots at the west end of the lot. Midday, families pull up in the shade of the overpass to open taco stands, unpacking folding tables and camp stoves.

Weeks before ten days of planned travel to Corsica, Genoa, and Nice with BX and SZ, days before I move unexpectedly for the second time in six months from one precarious rental location to another, two city blocks from my last apartment and a six minute bikeride from the one prior, coming up on three years back in my hometown after more than a decade away, I come across this excerpt from Simone Weil’s 1947 posthumously published collected writings, in the form of a disembodied piece of text online, offered without context, posted temporarily to instagram by friend and local LA poet LP.

It is necessary not to be ‘myself,’ still less to be ‘ourselves’.

The city gives us the feeling of being at home.

We must take the feeling of being at home into exile.

We must be rooted in the absence of a place.To uproot oneself socially and vegetatively.

To exile oneself from every earthly country.

To do all that to others, from the outside, is a substitute (ersatz)

For decreation. It results in unreality.

But by uprooting oneself one seeks greater reality.1

The spiritual preoccupations of Weil’s writing resonate with the material practice of my work as a community organizer with congregations of differing faith traditions across LA county. Participation in organized religion is declining, and dedicated spaces for worship are increasingly left empty and underutilized. We propose the unbuilding of these empty sanctuaries and temples, new uses for the adjoining parking lots that sit empty, instead constructing much-needed affordable housing, building flexible spaces for neighbors and community members to gather without the precondition of a shared faith tradition required upon entry. I consider my work beyond my day job, as an artist, writer, and regular convener of my communities, shaped by my conviction that architecture as a discipline, building itself, is a violent imperative. What we need are fortified practices of unbuilding, land back movements that will return land to indigenous stewardship.

In one sense, the act of reading is itself a practice in projection. In my effort to understand or relate to the material, I invariably layer my own interpretive lens, my own biases and positionalities, onto a text. Encountering Weil’s work as an isolated excerpt, there is additional space for me to fit its meaning around the contours of my current musings, preoccupied with ongoing unbuilding projects, upcoming travel, the change from one home to another for a fourth time since coming back to LA, experiencing a need for rootedness viscerally in my body, the need for that feeling of being at home in the city. Recently, I hear an excerpt of poet Ariana Reines describing the usefulness of collage as a technique, where things taken out of context —words, phrases, images, photographs, stories— and the subsequent act of cutting and pasting, is in service of exploration and movement.

What I feel is really interesting about these times is there’s so much language flowing through us, through screens, but you can’t cut into it. The cutout, as a technique, is actually a spiritual technique, it allows you to turn something that feels like a flow into a material. Once it is turned into a material, you can establish some agency, and also start to play again.2

The way she describes the cutout, the mediation of language through screens, conveniently justifies my notetaking practice. As T has often described it these past twelve years, I am “compulsively documenting” and “fiercely memorializing” everything in real-time, in physical notebooks and iphone notes, in a constant effort to extract material, to draw out connections and construct relationships through juxtaposition, using superimposition and integration to sort through and organize experiences and impressions. At times, this practice is meditative and generative; at others, I fear I am flattening and commodifying my experiences even as I have them.

Décollage, collage’s opposite, is defined as “the tearing away of parts of posters or other images which were adhered to each other in layers, so that portions of the underlayers contribute to the final image.”3 Examples of this technique include etrécissements, a reductive rather than additive Surrealist method of cutting away at an image, and cut-up technique, a Dadaist method for reconfiguring text. Negative space is the subject, the subtractive mechanism of removal the tool; a process of editing, rather than a process of layering; to cut through the patina, to create by undoing and dematerializing. This excerpt about uprooting oneself, I learn from LP, is from a chapter of Gravity and Grace called decreation.

Weil uses the word decreation to describe the undoing of individuated personhood, the unbuilding of individual perspective. Weil argues that ridding oneself of biases and preconceptions, detaching from expectation, leaves a person more actively engaged in looking and listening, capable of cultivating a type of radical attention that would make them more keenly aware of the needs of others and more attuned to their obligations to one another. In her writing, Weil’s reverence for god is unmatched except perhaps by her vehement opposition to organized religion, nation states, any type of groupthink that she perceived as stifling to critical thought.

In The Need for Roots,4 Weil names colonization as the destructive force causing uprootedness in people akin to the uprooting of plants. The divorce of a person from their sense of place, from where they are rooted in culture and collective identity, in ritual and belonging, results in spiritual and social death. A recent profile describes that Weil’s writing “radiates a cosmic empathy that coexists, sometimes on the same page, with a strain of intolerance blind to life’s tragic comedy. She resists any system that enslaves the individual to a collective, but her own vision of an enlightened society…is an autocracy modeled on Plato’s republic.”5 Still, Weil’s work insists on the human scale at every turn, emphasizing the cultivation of this radical attention.

Weil was born into an affluent family, grew up with luxury and the privilege of time for contemplation and study, proficient in Ancient Greek by age twelve, learning Sanskrit so that she could read Bhagavad Gita in the original,6 studying philosophy at the École Normale Supérieure. When she decided to give up her comfortable teaching position to fight with anarchist military unit the Durutti Column in the Spanish civil war, and subsequently to work in a factory, it was the careful watch of her parents that pulled her back out of trouble, repeatedly keeping her alive.7 Her uniquely privileged freedom of movement contextualizes her contradictions.

After these stints and a blowout argument with Trotsky,8 Weil amends her language from the Marxist oppression to affliction. Weil’s use of the word affliction indicates that the worker is not only alienated from the product of their labor, the worker is stripped of fundamental aspects of their personhood. Modern work harnesses a person’s attention such that revolution à la Marx is not conceivable, to Weil. Rather, in a system designed to deprive workers of the capacity to regain their own attention, the revolution must instead be spiritual.

Making and remaking home so many times the past four years, I watch my cat in each new city and new apartment we’ve moved to. People say that cats are more connected to the physicality of the space they live in, to the tactility of their material environment, than they are even to the people they’ve chosen as companions. ES first turns me on to Oulipian writer Georges Perec during the pandemic, in our extended dalliance of sending each other minutes-long, meandering voicenotes on the project of writing, sending excerpts from Species of Space between New York and Los Angeles:

4

Placid small though no 1

Any cat-owner will rightly tell you that cats inhabit houses much better than people do. Even in the most dreadfully square spaces, they know how to find favourable corners.9

It’s B who reminds me, at the onset of this latest sudden move from one rental situation to another, that I always manage to carve out a sense of home in the new place where I land. I lean on this reminder in small moments this fall, picturing my roots entangled with my closest neighbors—T, EL, SZ, BX, J, M, B, JR, MT, S, and O a mycelium network, radiating and interconnected.

When I first come back to Los Angeles three years ago, it was the tether of obligation and interdependence that brought me back from West Philly. I’d spent the better part of a year living off unemployment, biking up to a farm on the outskirts of the city where I was an artist-in-residence during the summer months, living alone for the first and only time in my life during a pandemic lockdown, located in a new city with only fledgling tethers to community, working gigs in Brooklyn, my professional connections still stronger in New York than in the city I had moved to, and I was running out of cash.

In my hometown, SC was still working full-time as a teacher at the high school where she and CC had first met at age fourteen, where my brother, sister, cousins, and I had all gone to school, while advocating for teachers during an ongoing pandemic lockdown, as president of the union for more than a decade, while she and CC continued to caretake full-time for my 外公 —anglicized as wai gōng, familiarized as gōnggōng— his slow-progressing dementia, his dog, SC’s mom’s mom’s mom —her grandmother, my great-grandmother, my gōnggōng’s mother-in-law— and the fast-progressing skin cancer just under her left cheekbone.

In those long afternoons of lockdown, SC would paste up six-foot-tall sheets of butcher paper on the bedroom walls upstairs and against the floor-to-ceiling glass windows of the downstairs living room at her childhood home, tracing our family genealogy in exacting detail, the enormous sheets of paper and big markers and SC’s exuberant presentation style a performance art piece for my great-grandmother. Tracing my gōnggōng’s side of the family, SC finds we are descended from the same Wyckoff line as painter Georgia O’Keefe, locates our ancestor, the ship’s painter J.A. McMullen10 who very nearly died in a shipwreck coming across the Atlantic from Ireland in 1873. SC traces her mom’s side of the family with the same determination, locating my great-grandmother’s biological sister despite the fact that my great-grandmother had been adopted very young and never known her birth parents.

Coming back freed up SC and CC to travel again, for the first time in more than five years, throughout which they’d been preoccupied with the obligations of caretaking, constant doctor visits and checkups, managing assortments of pills, reading salt content on prepackaged foods and ingredient lists to guard against hypertension, taking out the trash piling up on the countertop. “People hide from death as they age,” SC tells me, referring to the piles of stuff on the kitchen and dining room tables, the basement countertops, the laundry piling up on the bed, the piles of items that I compulsively clean and sort during the year I live at the house. Fresh off the end of a seven year romantic partnership, unable to pay my rent, living at my mother’s childhood home, I feel I am convalescing by the sea myself, keeping a close eye on my great-grandmother under the care of hospice nurses during that first month, and caretaking for my gōnggōng during the year that follows, in the wake of her death and through her pronounced absence in the house.

Years before the pandemic lockdown, SC and CC had planned to travel to Ireland for their thirty year wedding anniversary, for a range of collectively-held reasons including the genealogy project, SC’s fascination with and recent completion of James Joyce’s Ulysses, both of them wanting to learn about the entangled histories of religious and ethnic division in Northern Ireland, to hear about the Troubles from folks who had lived it. My parents, famously, had spent their honeymoon at the fall of the wall, incidentally catching Pink Floyd’s concert on the vacant land between Potsdamer Platz and the Brandenburg Gate, where they were served bottles of coke out the back of decommissioned military vehicles. As SC puts it, “these guys were so cheeky, they were just like, oh, guess we don’t have to shoot you now, we can just sell you a coke.” The stark juxtaposition of this imagery has stuck front-of-mind for me when I think about movement, experiencing a place in the wake of its more brutal realities and violent recent past.

Anticipating this trip, I buy SC a copy of Rebecca Solnit’s Book of Migrations at a favorite bookstore just south of Golden Gate Park, visiting former homes and neighborhood haunts in San Francisco and the East Bay, from my current rental address in New Jersey, stopping briefly in Manhattan Beach, before a research trip alone for a month in Osaka and Tokyo documenting a nation-wide grassroots network of community kitchens located in various public spaces including nursing homes, community centers, churches, and schoolyards. One year later, I return to an excerpt from this book through Alicia Kennedy’s writing in September 2020,11 framing out a distinction between travel and tourism, two words that are often presented as either interchangeable—merely a semantic distinction, or as dichotomous to one another—opposites defined supposedly by attitude or by socioeconomic class.

the tourism industry is perfect “for the information age: one of leisure, consumption, displacement, simulation” and “seems both to reverse colonialism and to repeat it; it is a means by which some of the wealth of rich nations returns to poor ones, but it is also a means by which the former continue to invade and dictate the latter… The vast and ever-expanding industry of tourism threatens to turn the whole world into a series of theaters whose companies perform palatable versions of their culture and history. Tourists thus possess a perverse version of Midas’s touch: the authenticity and exoticism they seek is unauthenticated and homogenized by their presence.”12

Traveling certainly reifies imperialism and colonialism more than it could be said to reverse it, since travel itself can be summed up succinctly as a “reflection of one’s earning potential in an inequitable economic system.”13 Significantly, the climatic implications, the excessive carbon emissions caused by planes, the exacerbation of global warming, is and will continue to disproportionately impact places and people least contributive to emissions globally.14

Beyond Solnit’s indictment, which centers on the doomed experience of the traveler or tourist, the adverse impact of travel on local inhabitants is well-documented.15 This has seemed, to me, to be especially true on island nations and at beachside locations, where the value of waterfront real estate enormously impacts the availability of products, goods, and services, bending local economies in favor of the traveler at the expense of locals. In Mindelo on São Vicente, Cape Verde, off the western coast of Senegal, inequities produced by the tourism industry were laid bare in anecdotes from locals, with whom we meet to discuss architectural ideas for the protection of culture and ritual, in a place shaped by its population of mixed-race descendents and by the violent history of Portuguese slave trade. I observe this divide between tourists and locals at the Oahu wedding of a childhood friend, whose grandparents are unable to travel off the island due to their elderly age. Living in West Philly during lockdown, I attend the BlackStar16 film festival, which features new work by Black, Brown, and Indigenous filmmakers, and bike out to see Christopher Kahunahana’s Waikīkī17 screened in the big plaza at the park,18 underlining aspects of Oahu’s tourism industry that had been entirely opaque to me as a mere visitor.

Throughout the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, the history of Bruce’s Beach becomes more widely-known, publicized beyond our one-mile-by-one-mile town. The once-thriving Black-owned beachfront resort had been seized by the city of Manhattan Beach in the 1920s through racist practices of eminent domain. A case for reparations, protestors pressured the city to legally transfer the land back to Charles and Willa Bruce’s descendents.19 At an event in my east LA neighborhood three years later,20 after the land has been transferred back to the Bruce’s descendents, and they in turn have sold it back to LA county, I listen to artist April Banks and community-engaged architect Theresa Hwang in conversation with real estate attorney George Fatheree III and Where is My Land co-founder Kavon Ward, and think about the land my high school was built on, farmland seized from Japanese Americans during internment, as SC reminds the students in her high school English classes every year. All this jostling to understand histories of land ownership, overlaid on the fundamental problem of uprootedness, the question of stewardship, how to return this land to inhabitants21 who can meaningfully guide our relationship to it.

This fall I’m still thinking about waterfront properties, beachfront development, island nations. BX puts me on to lectures by historian and theorist Manuel DeLanda when we come back from Genoa, a gritty, grimy port town that I love with feverish immediacy, anarchist graffiti in the streets and industrial machinery everywhere, enormous outdoor elevators dotting the city to accommodate pedestrian movement, severe grade changes within residential apartment blocks that carve out urban streetscapes that feel topographic, geological, cavernous. DeLanda describes the advent of capitalism in Europe through the work of Fernand Braudel,22 explaining the significance of port towns in facilitating the exchange of ideas, culture, economic systems, disease—Genoa was the locus for the rats who brought the plague by ship. BX, SZ, and I take a ferry from Genoa to Corsica, where the language is an Italian French creole. Driving around the island, we see signs shot through with bullets, eradicating French language and Italian language from the road signage, leaving only the signs written in Corsican intact.

Lately, I’ve been shooting film on an old minolta, like so many of my peers who’ve convinced ourselves that if we can just get away from the easy immediacy and convenience of the iphone camera, we’ll be capable of seeing the world in a different way, we’ll be able to redirect our attention. I don’t find that a new lens literally is any more helpful than a new lens figuratively, but the medium slows me down both when I am “at home” and “abroad.” Guy Debord’s 1967 work The Society of the Spectacle warns us about the mediation of life through images, through mere representation,23 but I hold out that there’s some worthwhile form of attention I am cultivating through this practice. Worth note, all photographs collected for this essay are former homes, places where I have contextualized myself over a prolonged duration, not merely traveled to or passed through.

Décollage, aside from being a subtractive artistic technique, is the literal French English translation for a plane taking off. The poetic description of a plane “becoming unglued” from the runway has stuck with me, a recurring intrusive thought when I travel to an unknown place or visit a former home. Sitting in the yard of my childhood home, the ambient “sky sound” of planes passing overhead is ever-present on that city limit between Manhattan Beach and Hawthorne, in the flight path to LAX. I consider Weil’s decreation and the aspiration of “becoming unglued” from myself. Recently, I mention to MB that I hope to challenge myself into being a new version daily, à la David Bowie, in response to his comforting encouragement, “you do you.” “I love that.” says MB, “Everyday revolution.”

“Tourism basically boils down to the leisure of going and seeing what has become commonplace,”24 Debord notes in Society of the Spectacle. As someone who specifically prioritizes time spent in corner markets, convenience stores, and grocery aisles anytime I am abroad, I would tend to agree with this description of tourism as an enchantment with the mundane. In a viral New Yorker piece from last summer, an academic named Agnes Callard describes her own rigidly myopic form of traveling, in which she flatly refuses to do what other travelers do, or does so, and then self-flagellates for having done so. She describes her time spent in Paris as an exercise in “suspending [her] usual standards for what counts as a valuable use of time” by walking through the city “over and over again, in a straight line; if you plotted my walks on a map, they would have formed a giant asterisk.”25

Several aspects of this image strike me as funny—first, the city grid of Paris does not lend itself to straight lines. The arrangement of arrondissements famously comprises a radiating series of concentric circles, interwoven and interspersed. Callard’s depiction of her walking path belies a blatant inattention to her surroundings, reveals her as the type of traveler who would transpose a preconceived American understanding of the city grid in, say, Chicago, and simply project that onto her idea of Paris, without paying attention to the realities or specificities of place, without allowing that place to redirect or reform her patterns of movement or interactions. Secondly, Debord’s 1956 theory of the dérive, formulated with the avant-garde Marxist collective Letterist International26 in Paris, proposed that free and open-ended wandering, not dictated by preconceived notions or adhering to the directives of a map, may lead to unexpected places and insights, impacting emotions and behaviors of wanderers through “psychogeography.” Contrary to Callard’s pronouncement that walking is a waste of time in her everyday life, I would argue that a regular practice of walking, at home and abroad, is a worthwhile practice.

This time last year, M and I are in D.C. with Palestinian Youth Movement, Jewish Voice for Peace, and If Not Now, to oppose U.S. funding of Israeli atrocities and the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people in Gaza, marching with the largest Jewish-led protest for Palestinian freedom and self-determination in history. Calling for a ceasefire, demanding an arms embargo, meeting people in the street, building together, remembering collectively, fueled by rage at the violence and death inflicted using our tax dollars only as much as we are fueled by our belief that a better world is possible, these are times when I’ve wanted to believe in god, or wished that I could, or wondered if I do. To travel, displacing oneself from known and familiar context, is at times an illusory attempt to escape the self, but principally, I’d like to think that these forms of exploration and movement operate in service of unbuilding the space between ourselves and others, cultivating a radical attention that subdues our preconceptions, making more visible our obligations to one another.

Simone Weil. Gravity and Grace. Routledge. New York, NY, 2002. [first published La Pesanteur et la grâce, Paris, 1947]

Ariana Reines & Invisible College: a fugitive study hall for poetry, the sacred, & the arts. https://www.patreon.com/c/invisiblecollege/posts

ArtLex Art Dictionary. 2005 at the Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20050424084418/http://www.artlex.com/

Simone Weil. The Need for Roots: prelude towards a declaration of duties towards mankind. Routledge. 1949. [first published L'Enracinement, prélude à une déclaration des devoirs envers l'être humain, 1949]

Judith Thurman. “The Supreme Contradictions of Simone Weil.” The New Yorker. 2 September 2024. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/09/09/simone-weil-a-life-in-letters-robert-chenavier-andre-a-devaux-book-review

Katie Tobin. “The Enigma of Simone Weil: Anarcho-syndicalist, Catholic, Marxist, mystic: Simone Weil remains one of the twentieth century’s most compelling and enigmatic philosophers. Recent years have seen an increasing number of writers turn to her work for inspiration, but what the left gain from her difficult, often contradictory writing?” Verso. 28 February 2024. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/the-enigma-of-simone-weil?srsltid=AfmBOoqNcJDoHzldKEzhbLbtFrezJoOeeXmMHe5w1TbbwWJ4ScQpFd40

Stephen West. “Simone Weil: Attention.” Philosophize This! podcast. 31 October 2022.

Peter Salmon. “Simone Weil Was a Saint of the Socialist Movement.” History/Theory, Jacobin. France, 2 January 2023. https://jacobin.com/2023/01/simone-weil-philosophy-marxism-anti-fascism-labor-suffering

Georges Perec. Species of Space and Other Pieces. Penguin Books. London, 1997. [first published Espèces d’espaces, 1974]

Brooklyn Eagle, page 4. Monday, 23 June 1873. https://www.newspapers.com/article/brooklyn-eagle-james-mcmullen-arrival-23/69469679/

Alicia Kennedy. “On Traveling: Part two of my inquiry into the meaning of movement.” 7 September 2020. https://www.aliciakennedy.news/p/on-traveling

Rebecca Solnit. A Book of Migrations: Some Passages in Ireland. Verso, 1998.

Alicia Kennedy. “On Going: The first in a two-part inquiry into the meaning of movement.” 31 August 2020. https://www.aliciakennedy.news/p/on-wanderlust

Bethany Tietjan. “Many of the world’s poorest countries are the least polluting but the most climate-vulnerable. Here’s what they want at COP27.” Science. 2 November 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/many-of-worlds-poorest-countries-are-the-least-polluting-but-the-most-climate-vulnerable-heres-what-they-want-at-cop27

Jasmine Osby. “Why Tourism in Hawaii is causing Natives to Lose their Homes.” Travel Noire. 23 August 2023. https://travelnoire.com/why-tourism-in-hawaii-is-causing-natives-to-lose-their-homes

BlackStar Fest. https://www.blackstarfest.org/

Gary M. Kramer. ““Waikiki” filmmaker: “Hawai’i is marketed as a paradise…but things are only getting worse: Native Hawaiian director Christopher Kahuahana spoke to Salon about his dark, surreal film about indigenous trauma.” 26 October 2020. Salon. https://www.salon.com/2020/10/26/waikiki-film-christopher-kahunahana/

Jeff Chang. “Waikīkī and Its Discontents.” Issue 03. Fall 2021. https://www.blackstarfest.org/seen/read/issue003/waikiki-and-its-discontents/

The Guardian. “Bruce’s Beach to be returned to Black family 100 years after city ‘used the law to steal it’: California governor apologizes for city’s seizure of first west coast resort for Black people, which almost certainly would have made heirs millionaires.” 1 October 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/oct/01/bruces-beach-returned-100-years-california

Dreaming Land Back Into Reality. Clockshop. 21 January 2023. https://clockshop.org/project/dreaming-land-back-into-reality/

David Treuer. “Return the National Parks to the Tribes: America’s landscape should belong to America’s original peoples.” The Atlantic. May 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/05/return-the-national-parks-to-the-tribes/618395/

Manuel DeLanda. The City and Capitalism. 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQNfNbES9oA

Guy Debord, translated. Fredy Perlman. The Society of the Spectacle. Black & Red, 1 June 2000. [first published La société du spectacle, 1967]

Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle.

Agnes Callard. “The Case Against Travel: It turns us into the worst version of ourselves while convincing us that we’re at our best.” The New Yorker. 24 June 2023. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-weekend-essay/the-case-against-travel

Guy Debord. “Theory of the Dérive.” Internationale Situationniste #2, Paris, December 1958.