According to one viral tweet from October 2020, “There was never any lockdown. There was just middle-class people hiding while working-class people brought them things.”1 Approaching March 2024, four years since the US government first issued pandemic lockdown orders, these divisions continue to hold as more arise between people differently affected by covid infections, deaths, hospitalizations, and untreatable long-covid symptoms. Pandemic fallout, filtered through news coverage and social media in recent years, has been underscored by a colloquial distinction between “people” and “workers.” With regard to foodways, “worker” has been an umbrella term for servers, cooks, dishwashers, grocery clerks, gig workers employed by delivery apps, and food procurers and producers broadly.

Food structures our built environment; bodily and programmatic need, ritual, and routine designate spatial relationships. Because the design of buildings and urban infrastructure has long separated laborers from employers, suppliers from consumers, service workers from individuals being served, service space has shifted typologically but continually reinforced social division and hierarchy against this line. As a programmatic typology, the restaurant separates consumer from cook in the back-of-house restaurant kitchen. The use of back alleys, service doors, and freight elevators invisibilize service space while the stage is a celebrated site of communal dining.

“Americans have grown ever more estranged from the sources of their food and the largely unseen labor required to produce it,”2 writes Ligaya Mishan in 2021. “Invisible people” Francis Lam identified in 2018, “often anonymous cooks and growers, who are largely immigrant or underrepresented communities, fuel this industry that now has so much cultural cache.”3 Display kitchens, farm to table dining, the rise of fast casual restaurants, and other markers of this cultural cache have contributed to a pre-pandemic neoliberal culture in which food consumption and production is regarded by some as de-politicized and post-class. Designers and architects of these spaces are incentivized to showcase commodities and promote consumption, most often with designs that actively hide the realities of labor and production.

Sociologist Sarah Bowen states that “in the past [not all] Americans were cooking their food. They were often relying on low-income women of color to cook a lot of it, and they still are. It’s just that it used to be in the house, and now it’s in restaurants.”4 In his 2009 book Kitchens, Smokehouses, and Privies: Outbuildings and the Architecture of Daily Life in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic, Michael Olmert describes kitchens, laundries, smokehouses, dairies, privies, offices, dovecotes, and icehouses as typological forms in which service labor was concealed and separated from dwelling spaces.

“The culture of outbuildings was made possible by vast class differences, economic hardships, servitude, and slavery… The food preparation area was the utilitarian realm of a hardworking underclass… Food was prepared in a lowly kitchen, often in a cellar below the great hall, and was dramatically delivered on to a much more exalted stage— a banqueting hall in the Old World, a dining room in Anglo-America. It was eating as theater.”5

This distinction between service space and stage has a spatial analogue in the 17th century English home. In his 1978 text Figures, Doors and Passages, Robin Evans describes an architectural turn that “indicated a change in mood concerning the desirability of exposure to company, whether to all in the house, or just to some.”6 This turn from Palladianism to the manors and estates of the wealthy in 1600s England provided “on the one hand, an extended concatenation of spaces to flatter the eye; on the other, a careful containment and individual compartments in which to preserve the self from others.” According to one architect of the period, Sir Roger Pratt, this planimetric design favoring the corridor over interconnected rooms was intended to ensure that “ordinary servants may never publicly appear in passing to and fro for their occasions there.” The “self” to be “preserved from others” referred precisely to the servants who cleaned, did the laundry, cooked all the meals, and tended to the various needs of homeowners. Separate stairways, separate entrances, separate corridors, meant that domestic work —commonly coded as dirty, laborious, and slow— could be made invisible to the homeowners despite their total dependence on that labor.

Architect and historian Mabel Wilson’s analysis of Monticello, the plantation home of enslaver and US president Thomas Jefferson, delineates a clear separation between service space and stage. Wilson observes that Jefferson’s 1786 designs

“deployed the architecture convention of the section to place the spaces where enslaved people worked out of view. His placement of dumbwaiters near his fireplace made the work of black servants invisible during intimate dinners… These architectural designs could be understood as encompassing a strategy of denial rather than reconciliation.”7

This denial rather than reconciliation has carried through from the domestic space of the private home into the public space of the restaurant. In the mid 1820s, Thomas Downing’s Oyster House became a “watering hole for the elite” in a time when oysters were abundant and affordable, an everyman food eaten very cheaply outside at a roadside stand or in dingy bars. Museum curator Joanne Hippolite explains that Downing

“operated two properties that were adjoined, on Broad Street, so that gave him an expansive footprint. These other cellars were known as these rough-and-tumble places with dim lights… Thomas Downing had a large dining area, curtains, a fine carpet, he was known for having a chandelier in his space, so this was fine dining. His clientele were largely white men, men of means, merchants, bankers, Wall Street types.”8

Thomas Downing was an African American man whose parents had been enslaved and set free, so he grew up a free man on Chincoteague, where his family’s livelihood was sustained by clamming, digging, raking oysters, and fishing. After running an oyster bar in Philadelphia for 7 years, Downing opened his New York city restaurant, catering largely to white clientele while serving as a stop on the underground railroad, harboring black individuals who had escaped enslavement in his cellars. Downing was a founding member of the community group “The Committee of the Thirteen,” which helped protect free African-Americans, and the wealthy white clientele of his Oyster House likely had no way of knowing that the money they used to pay for their meals was partly funding the escape of formerly-enslaved African Americans.9 Stephen Satterfield’s 2021 documentary notes that Downing was “able to navigate these two worlds so seamlessly”.10 One of the seams between these two worlds was the front-of-house back-of-house divide.

While we’re watching cooks call out to each other on the line at a favorite diner counter yesterday morning, I’m talking about this diagrammatic line between service space and stage when MT mentions our friends’ house, which we frequent for parties, and where they used to live for years. “You know that’s the servants quarters, right? Have you not been in the main house yet?” The cramped kitchen and narrow hallways between rooms houses six of our friends, but MT tells me that the main house has got closer to ten roommates at any given time, still housed cheaply, but in bigger, more generous rooms. The stair to the front porch of that house opens onto the main street, with a generous front yard.

“That’s why there’s no living room! That’s why a party is just sitting outside at that wooden table on the shitty back alley,” MT laughs affectionately of their old house. It’s true, whenever we go over, it’s warm in the kitchen, there are cassettes playing from the tape deck in the corner, people making hand crafts, stringing up decoration on the iron light fixture, making each other mulled wine and feeding each other donuts and pastries pulled down from on top of the fridge, no counter space to speak of and no designated places to sit; we are piled in front and behind each other standing next to the stove in front of the bathroom door, sitting practically on top of each other on the extremely narrow and steep 1900 wooden staircase. In all my years of cooperative cohousing, I’ve been most charmed by the particular intimacy of chaotic kitchen cohabitation. Understanding this space as the servants quarters, it’s clear that the small rooms strung between narrow hallways don’t architecturally account for communal gathering or rest.

Understanding service space and stage as a dichotomy with historic precedent, projecting into the near future we can see that these spatial trends will be further exacerbated by automation and continued reliance on food delivery apps like Seamless, Grubhub, Doordash, Caviar, and Ubereats, among others. Already, the growing phenomenon of “dark kitchens” in dense metropolitan centers has evidenced further separation of consumers from cooks. In London, a food service app uses the name recognition of chefs in the city to advertise food that is actually cooked in cramped, windowless, unventilated shipping containers, outfitted with industrial kitchen equipment, under motorway intersections miles out from the city center.11

“A lot of restaurants in the UK are closing because of [a food service called] Deliveroo, which brings you restaurant-quality food on the back of a bike. But a lot of that food is not actually cooked in restaurants at all, but in so-called “dark kitchens”: portacabins under motorway flyovers.”12

The pandemic made divisions explicit; “essential workers'' are expected to continually risk their lives and put their health on the line without government support while simultaneously receiving hollow praise for their heroism. New designs for spatial separation within restaurants have gone to great lengths to protect the consumer, a paying customer, while neglecting to take the same safety measures within the back-of-house service space to protect cooks, dishwashers, or servers. Elaborate outdoor dining setups, new takeout windows with plexiglass shields, and entirely enclosed tent structures sited on public sidewalks invariably privilege consumer comfort over the needs of servers. One explicit diagram of this divide are the plastic bubble-shaped tents for outdoor dining that have populated city streets and sidewalks from Toronto, San Francisco, New York, and Philadelphia, frequently displacing houseless populations. Food and culture writer Soleil Ho wrote in August 2020,

“In a queer reversal, the dome is a shield against, not for, the ones who need sheltering the most. Its shape and transparency are both a visual echo and rebuttal to the multicolored rows of dome-shaped tents that line the streets of downtown San Francisco: An unhoused person’s tent is erected in a desire for opaqueness and privacy, whereas the fine dining dome invites the onlooker’s gaze as a bombastic spectacle.”13

Ultimately, these staged precautions are ineffectual because servers are forced to interface indiscriminately with customers and cooks, carrying the virus back and forth, and proving the hollowness of this bombastic spectacle.

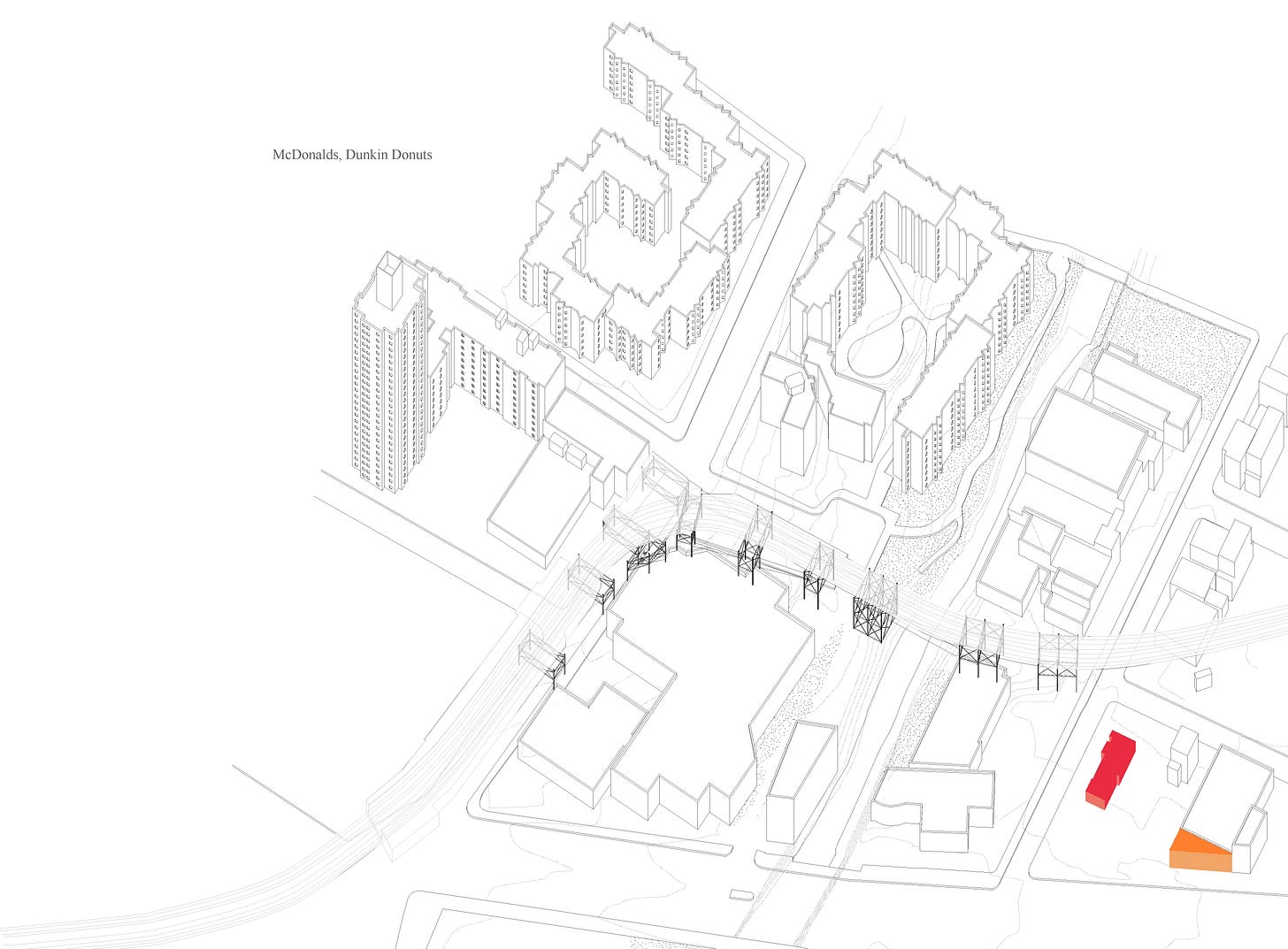

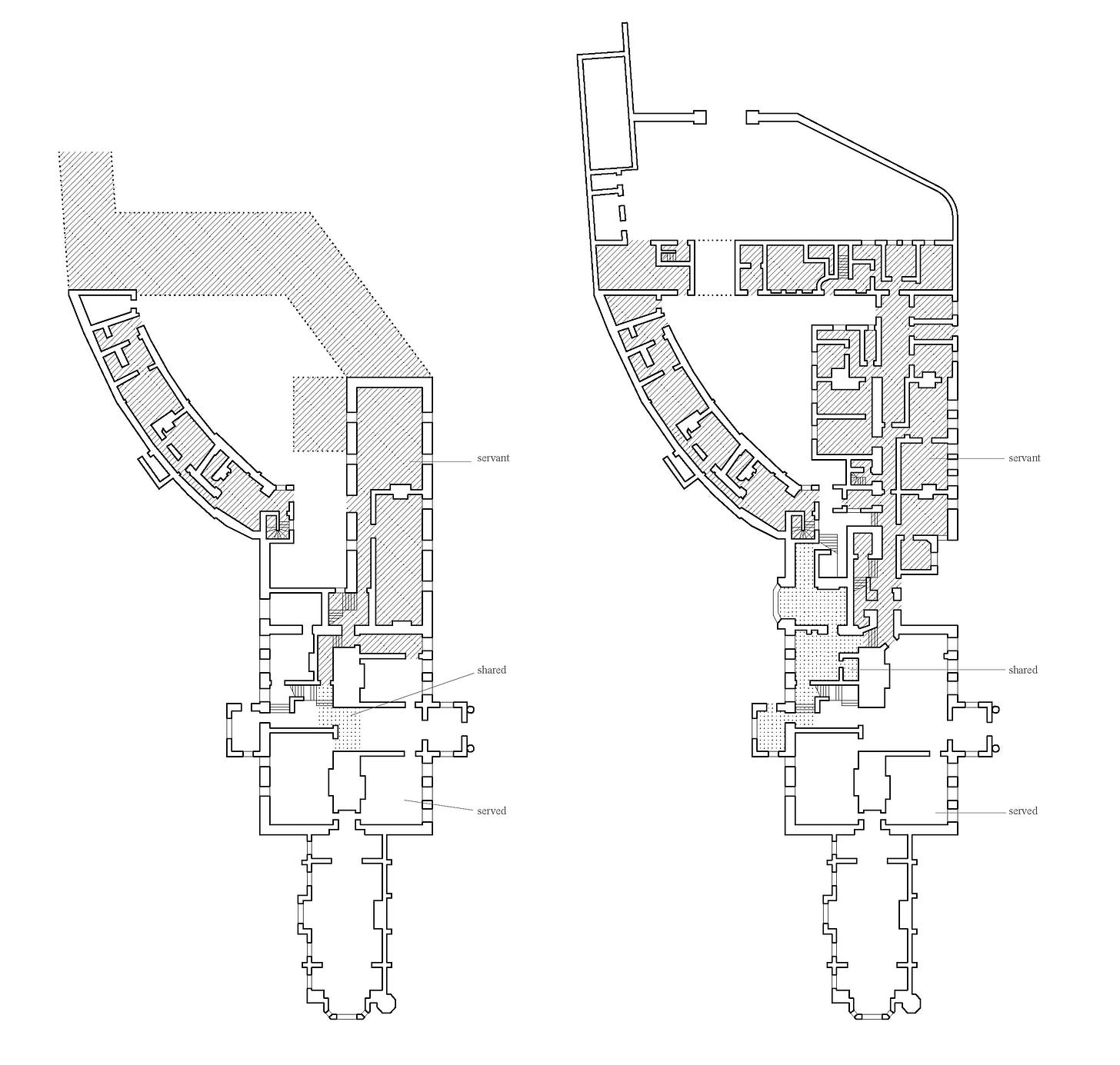

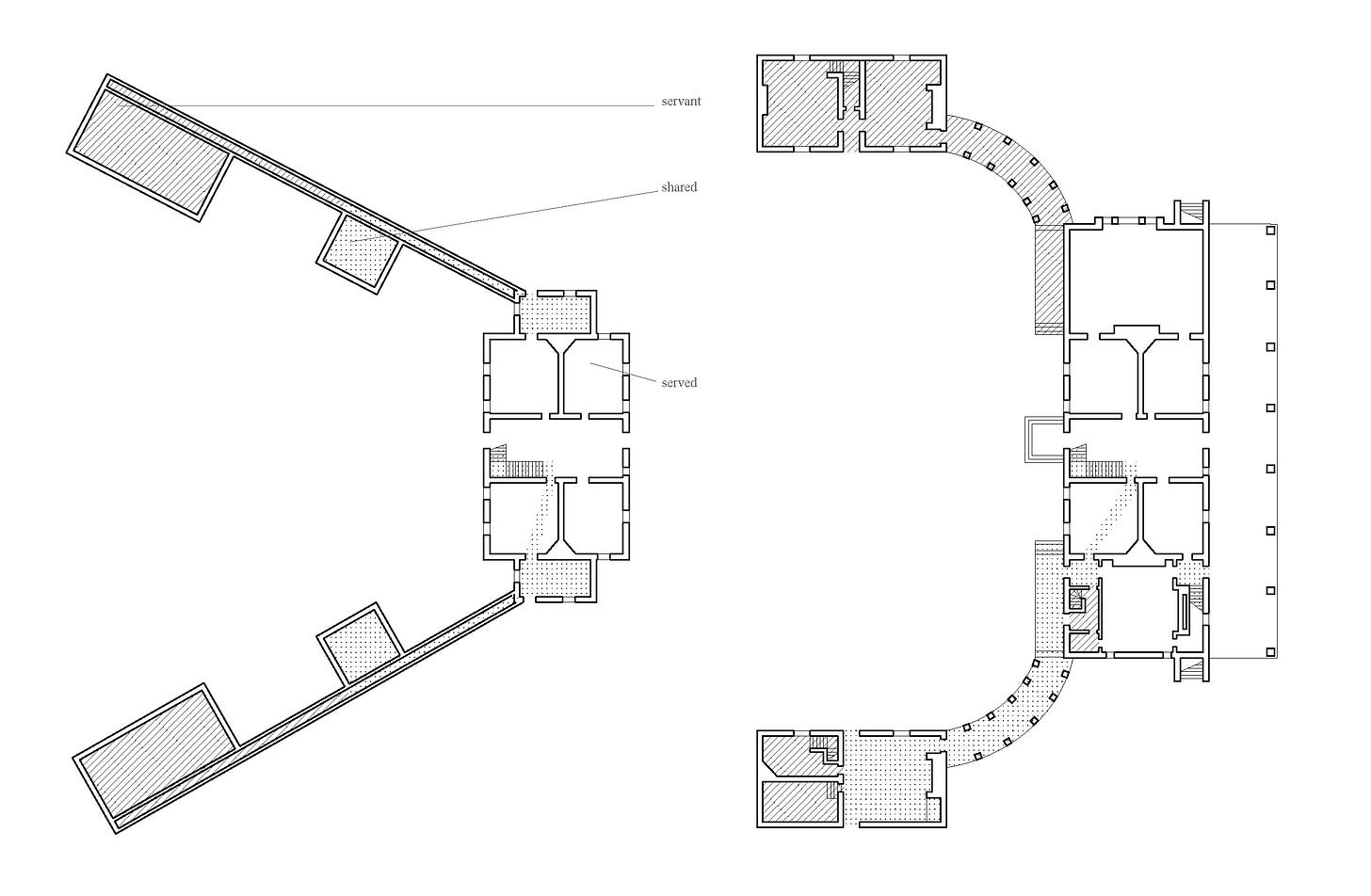

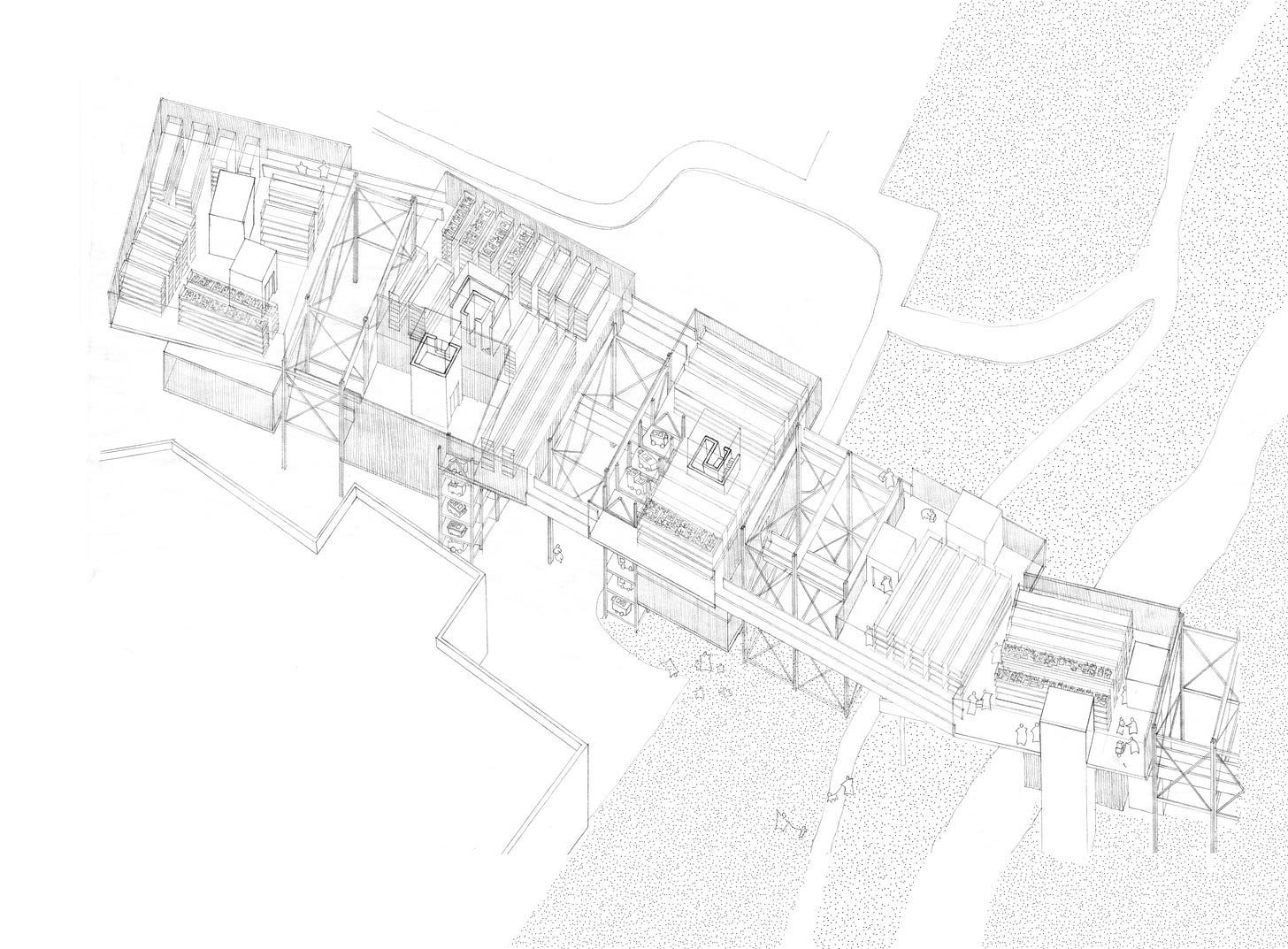

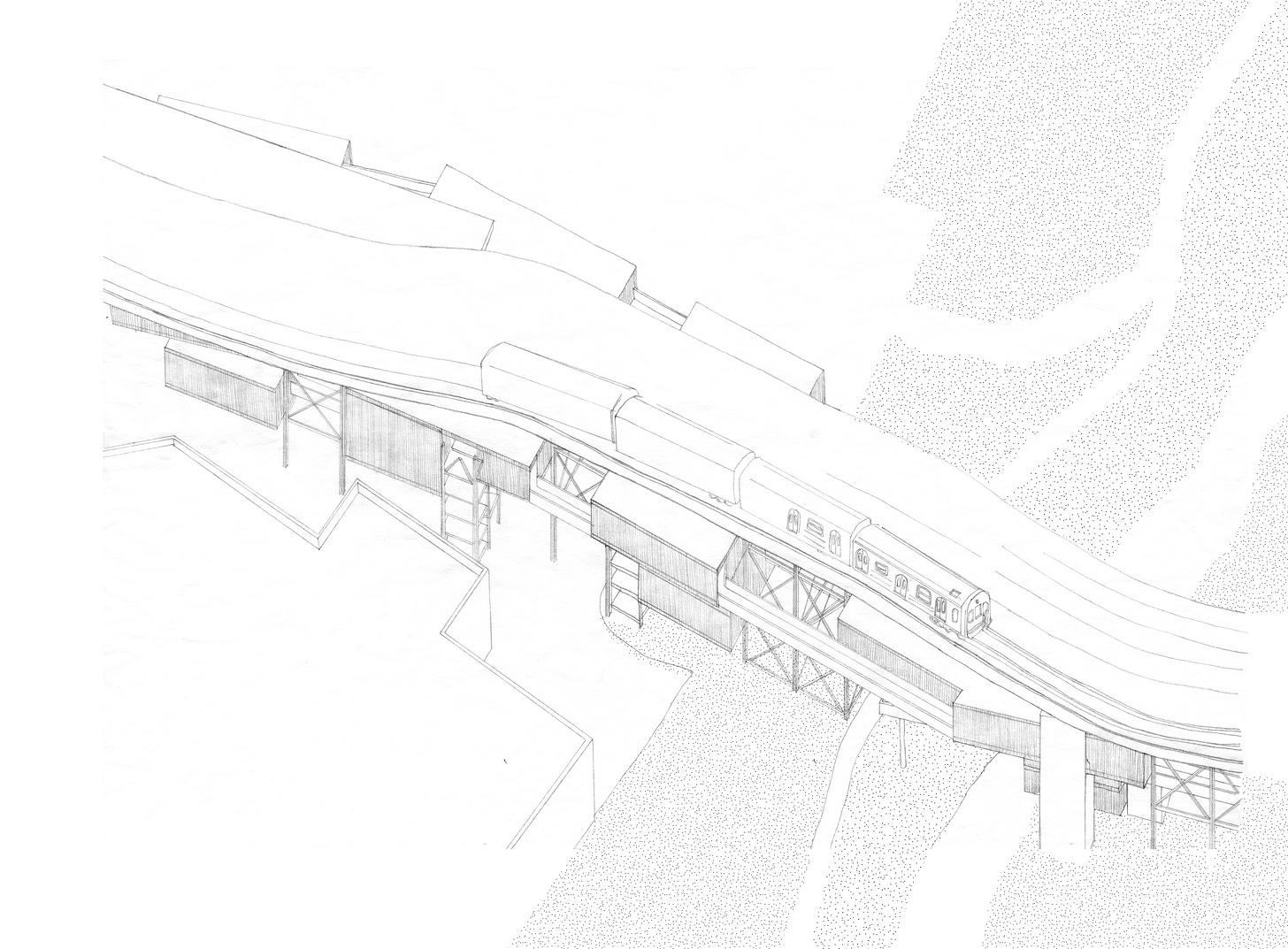

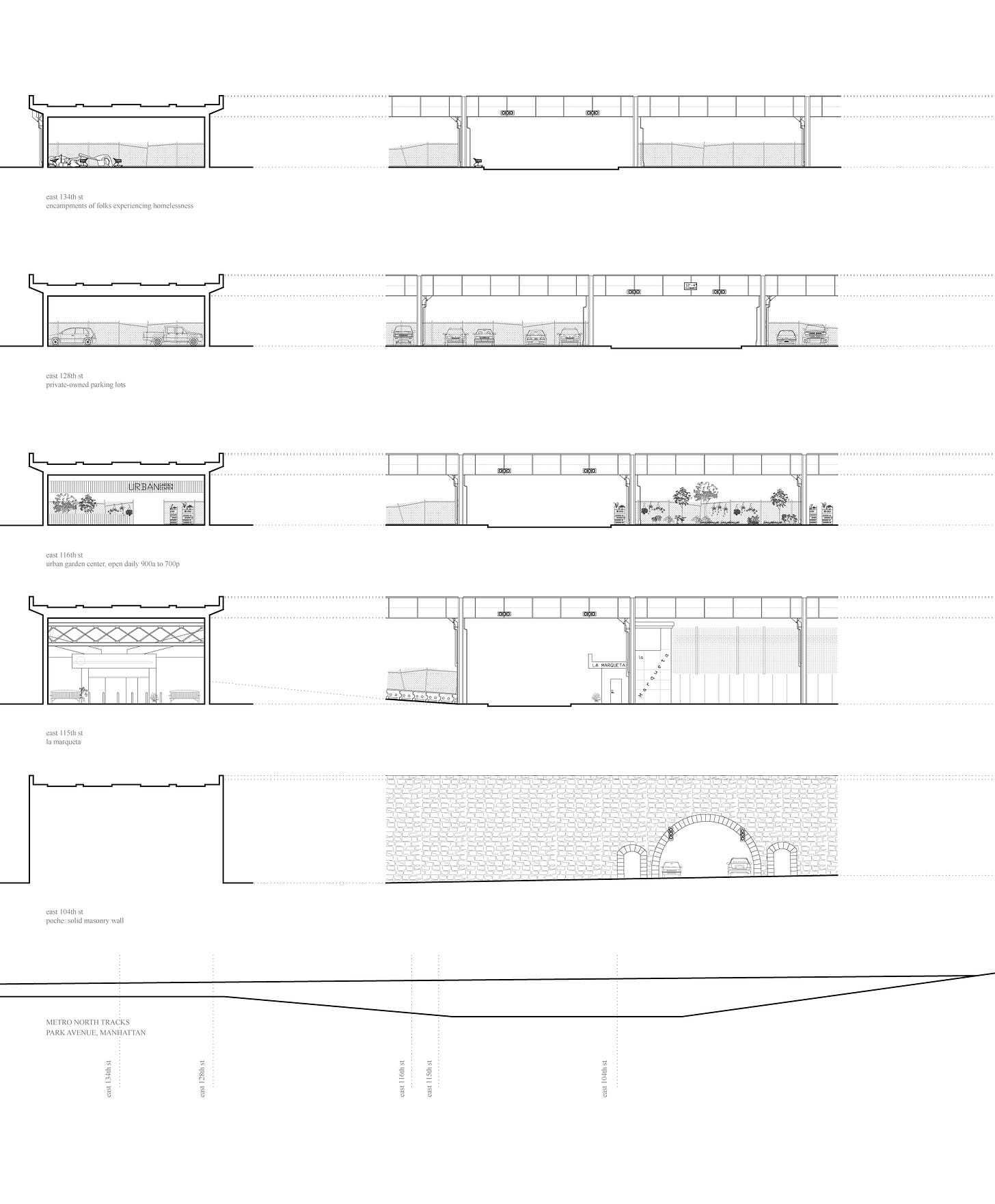

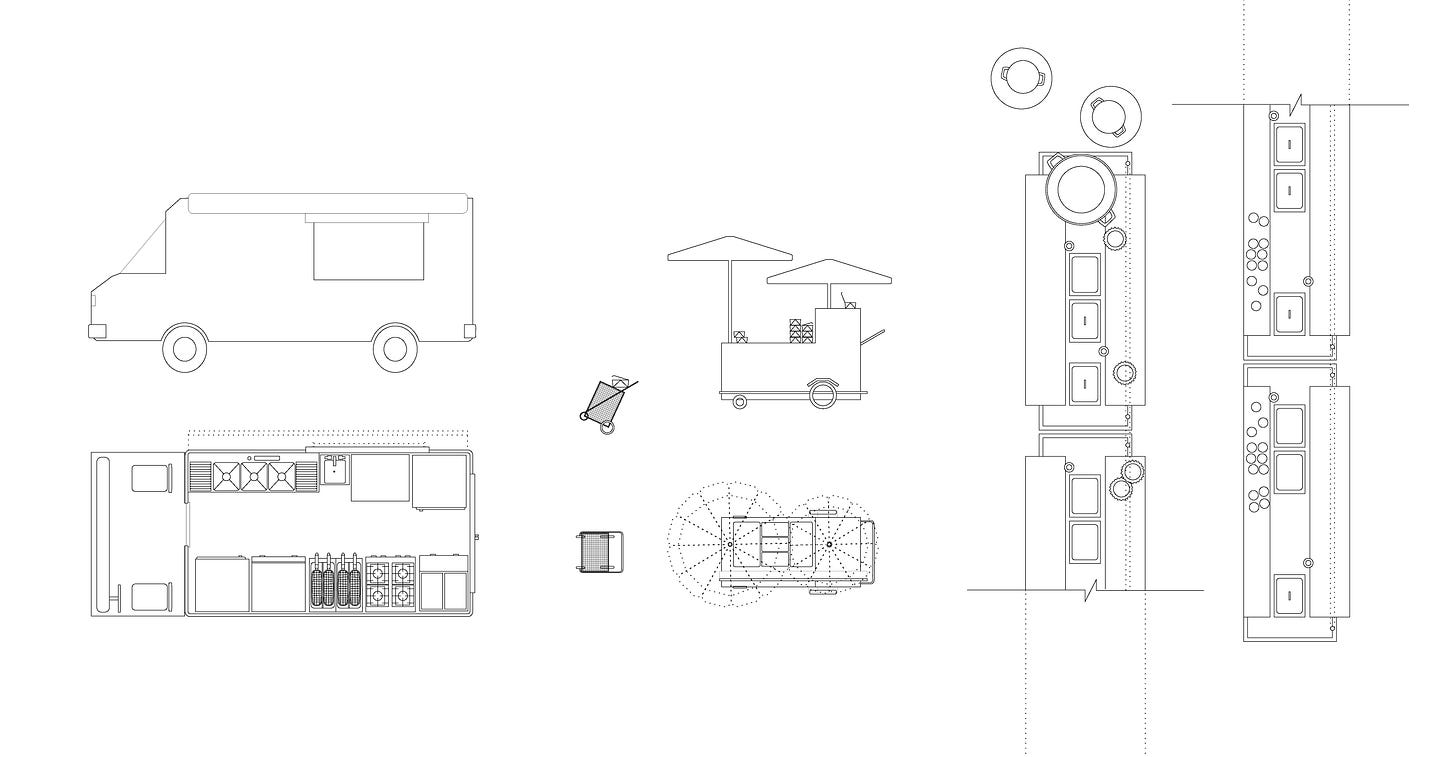

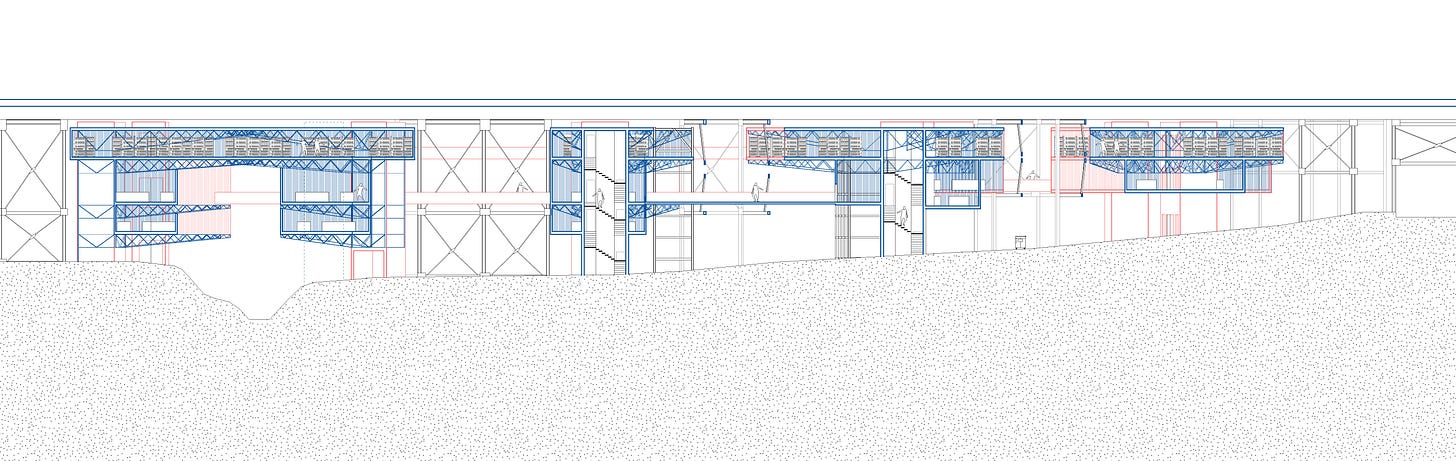

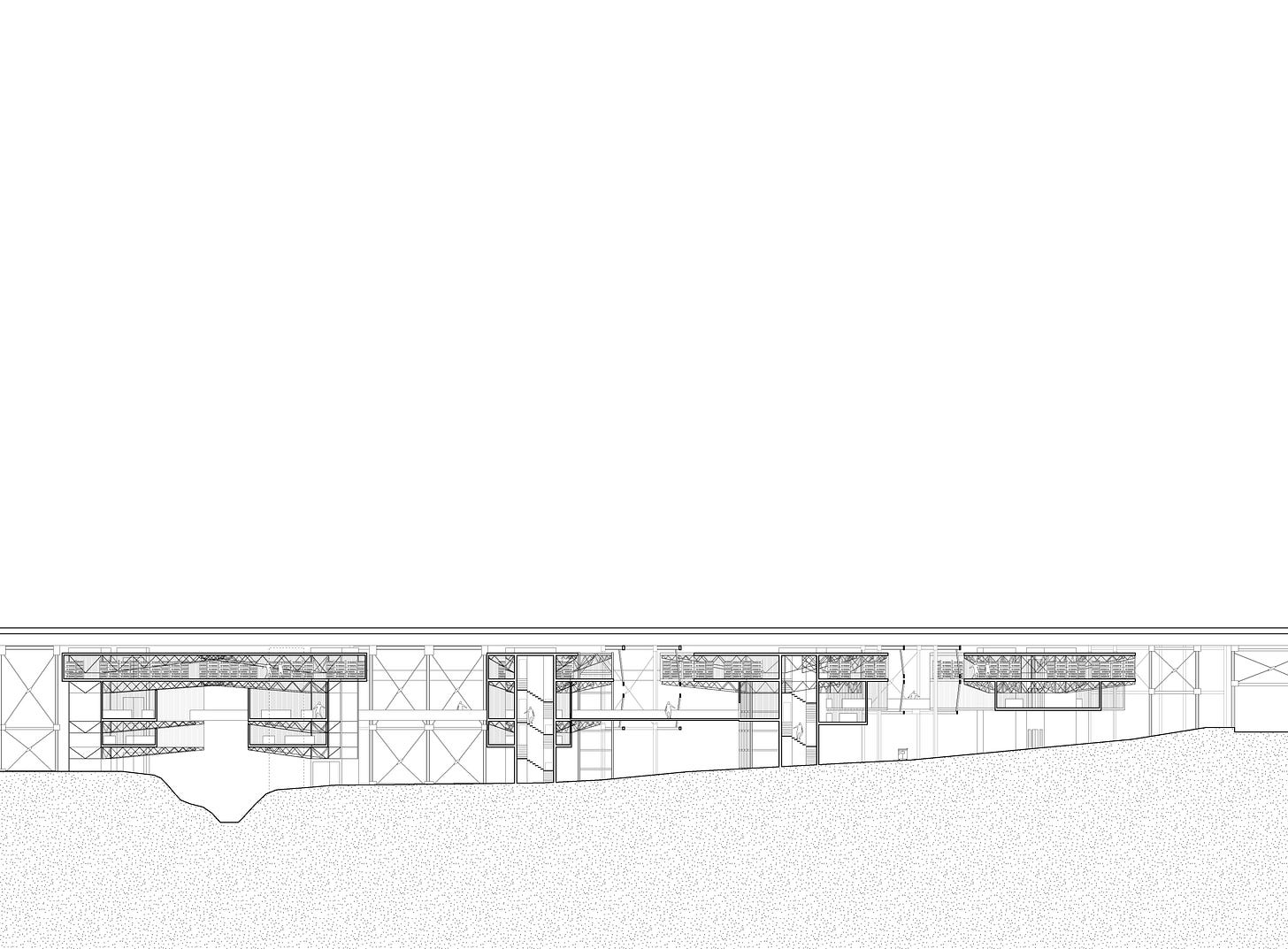

In this context, I proposed a project in spring 2020 for a city-wide initiative to build community kitchens in the interstitial space under New York’s elevated rail. The construction of freeways and elevated subway lines has historically divided communities and segregated neighborhoods. The interstitial kitchen stitches across this unoccupied space under the elevated rail to service the spatial and material needs of street food vendors and their local communities. A brick-and-mortar restaurant typically separates cook from consumer, invisibilizing food production processes. The guerrilla kitchen, here defined as mobile food carts, stands, or trucks, comprises an informal economy that contests this divide, catalyzing interaction between cook and consumer in the exchange of food on the street.

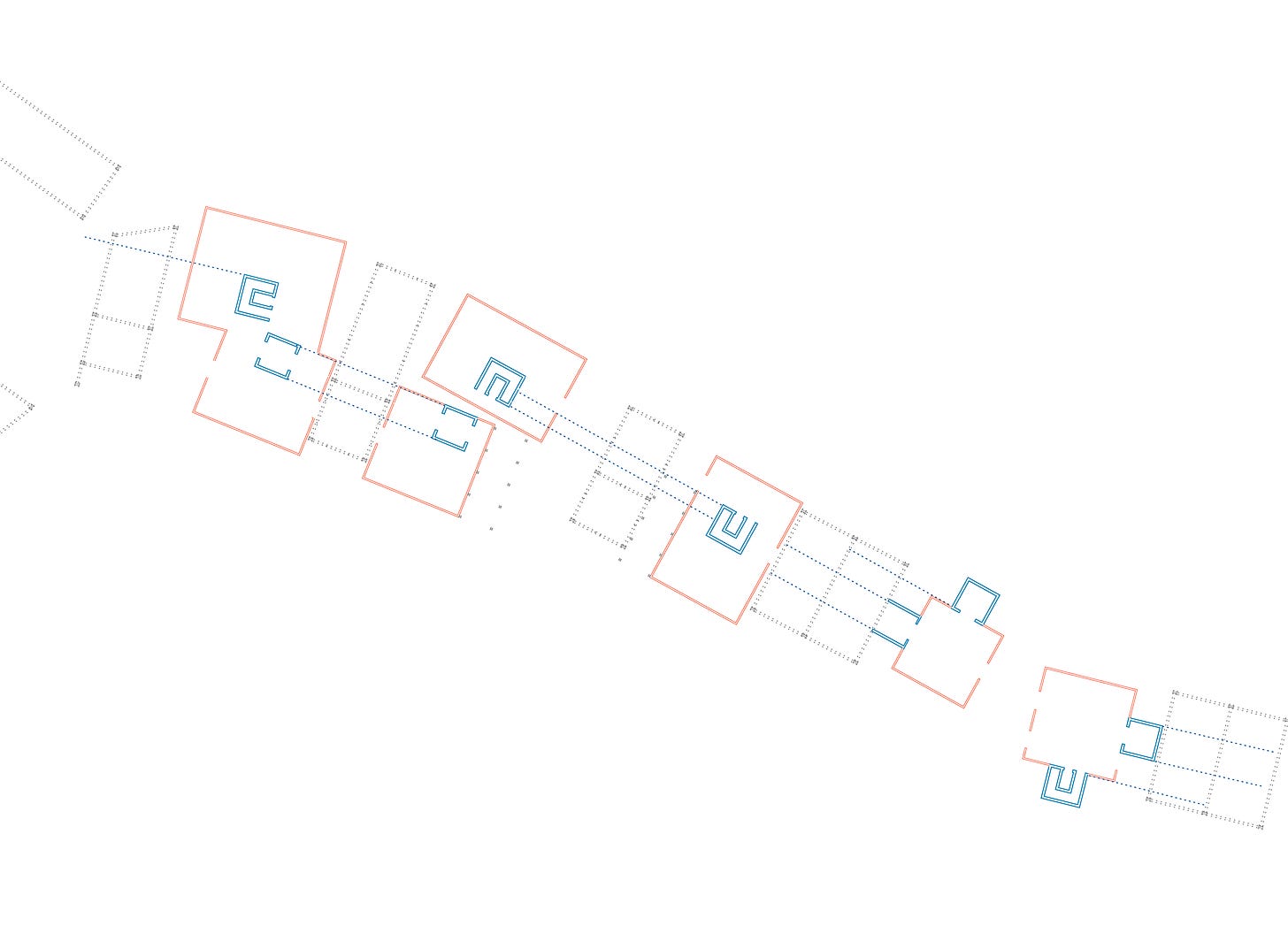

Street vendors are a precarious workforce, dispersed and non-unionized. For many, storing carts at home would be most convenient but city-wide food safety regulations prohibit this, and law enforcement looks for excuses to fine violators. Certified commissary locations provide overnight parking — several New York locations in Brooklyn, Queens, Harlem, and the Bronx are mapped below. As a garage/kitchen typology, vendors pay rent to park and wash their vehicles or use shared commissary kitchens.

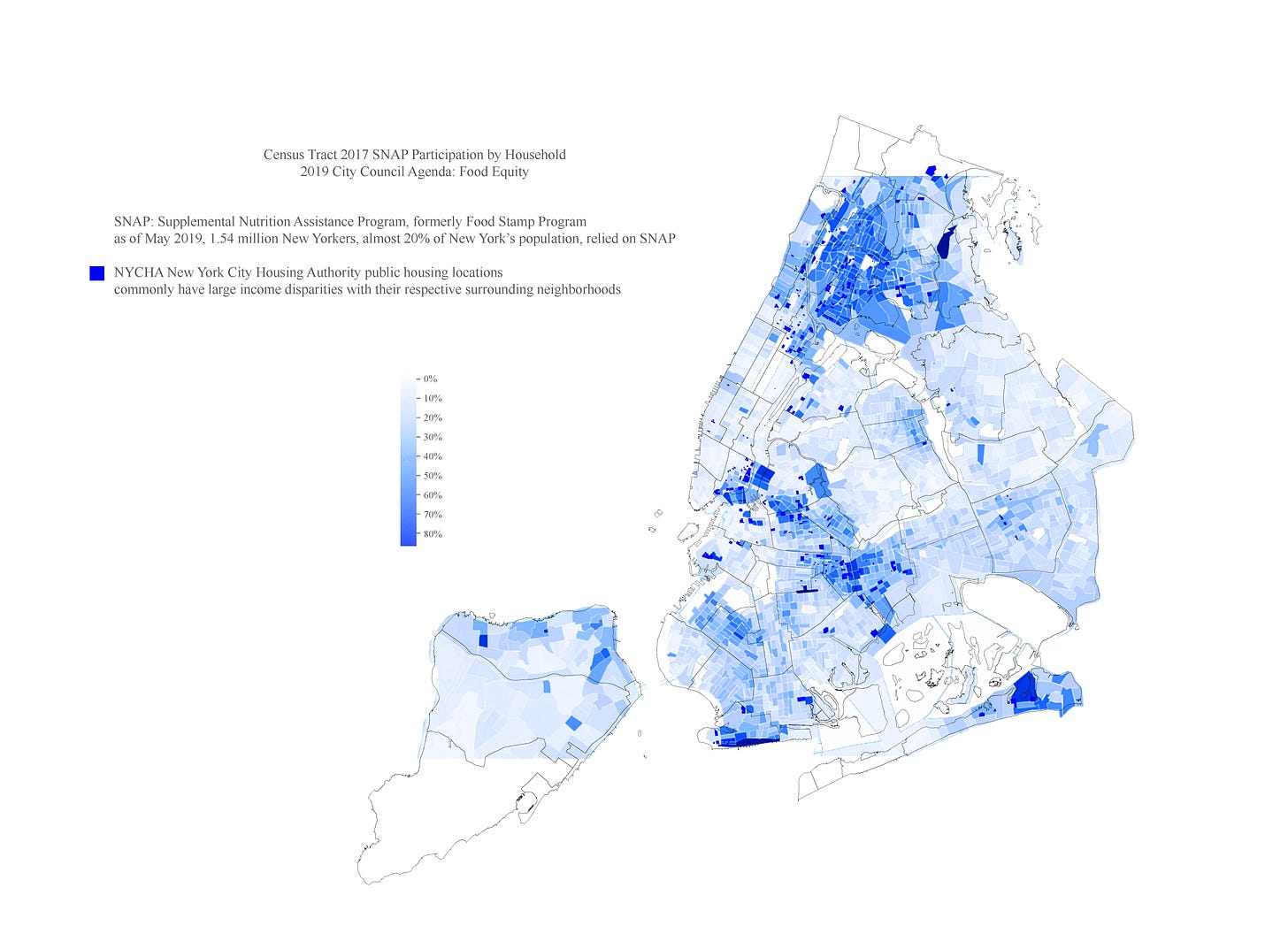

Commissaries are privately owned, charging high rates for storage and access, and presenting an insurmountable barrier for many vendors, who instead use folding tables, the back of pickup trucks or vans, tarps, and other makeshift stands. According to a 2019 report by the Urban Justice center, a survey of street vendors showed that “77% live in Queens, Brooklyn, or the Bronx.”14 These outer boroughs are also the most food insecure, according to a 2017 study estimating just over 1 million food insecure New Yorkers. The highest concentrations15 of SNAP participants, formerly known as the food stamps program, maps on to roughly the same neighborhoods. An estimated 1.5 million New Yorkers relied on SNAP as of May 2019.

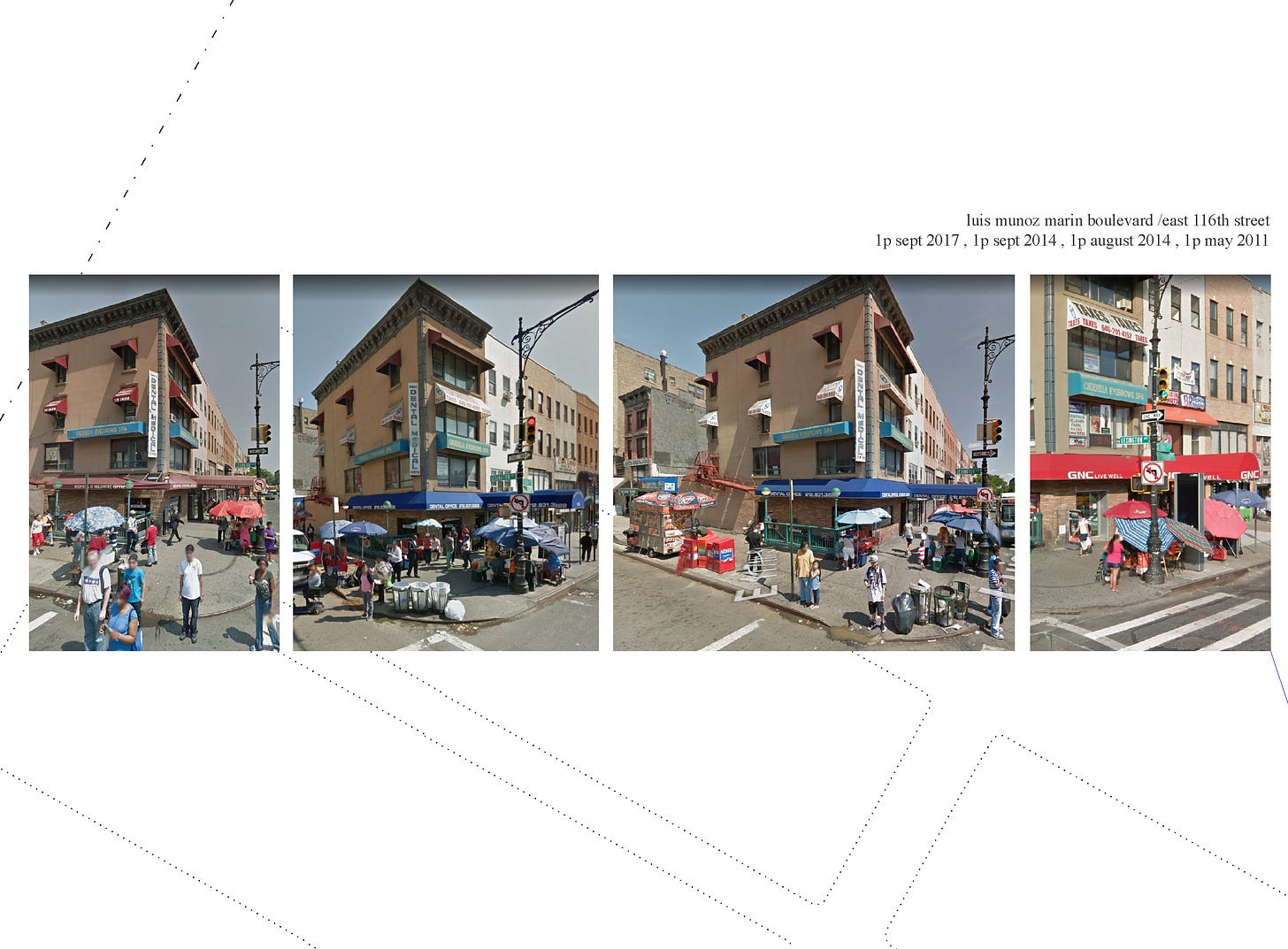

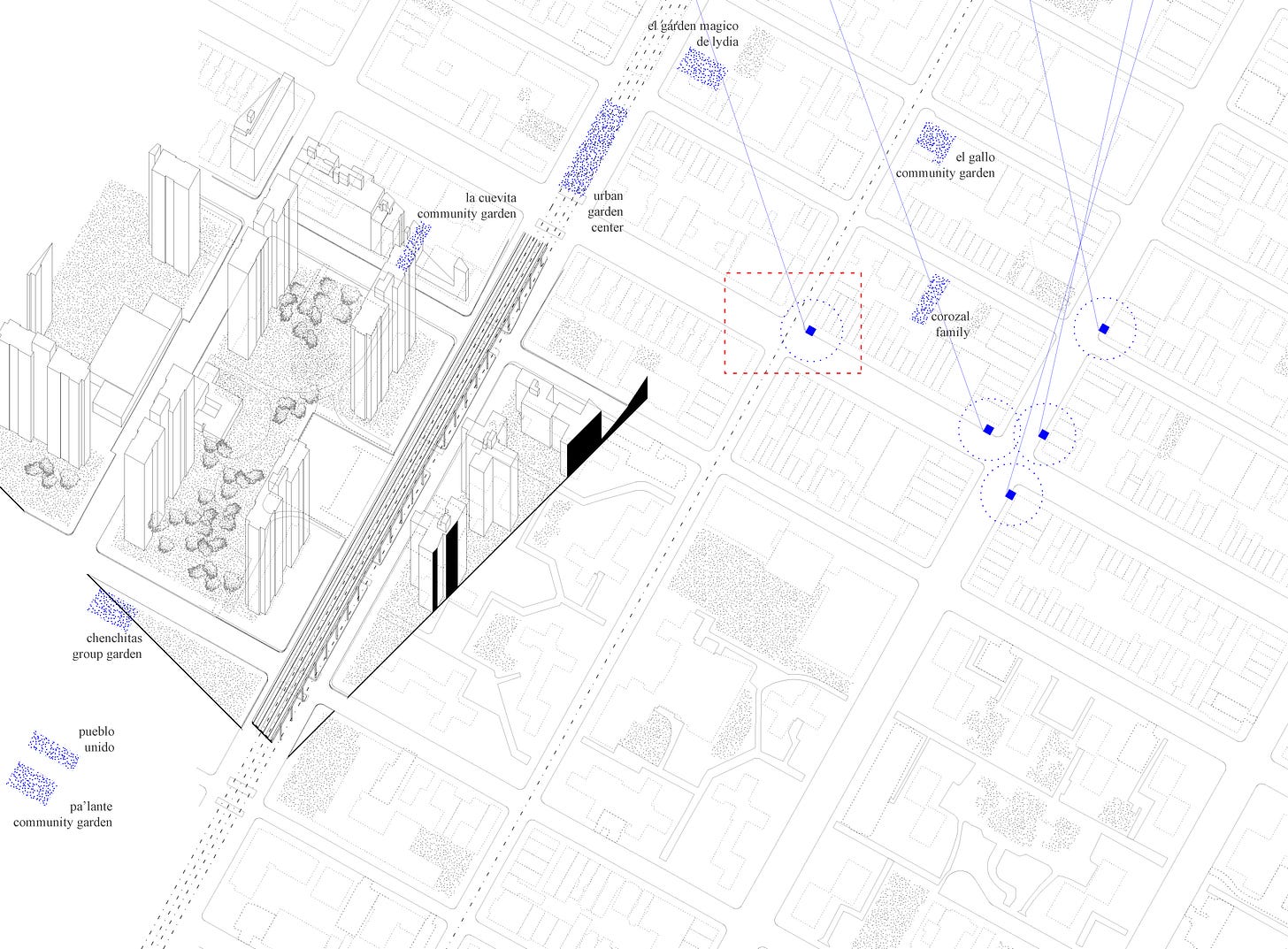

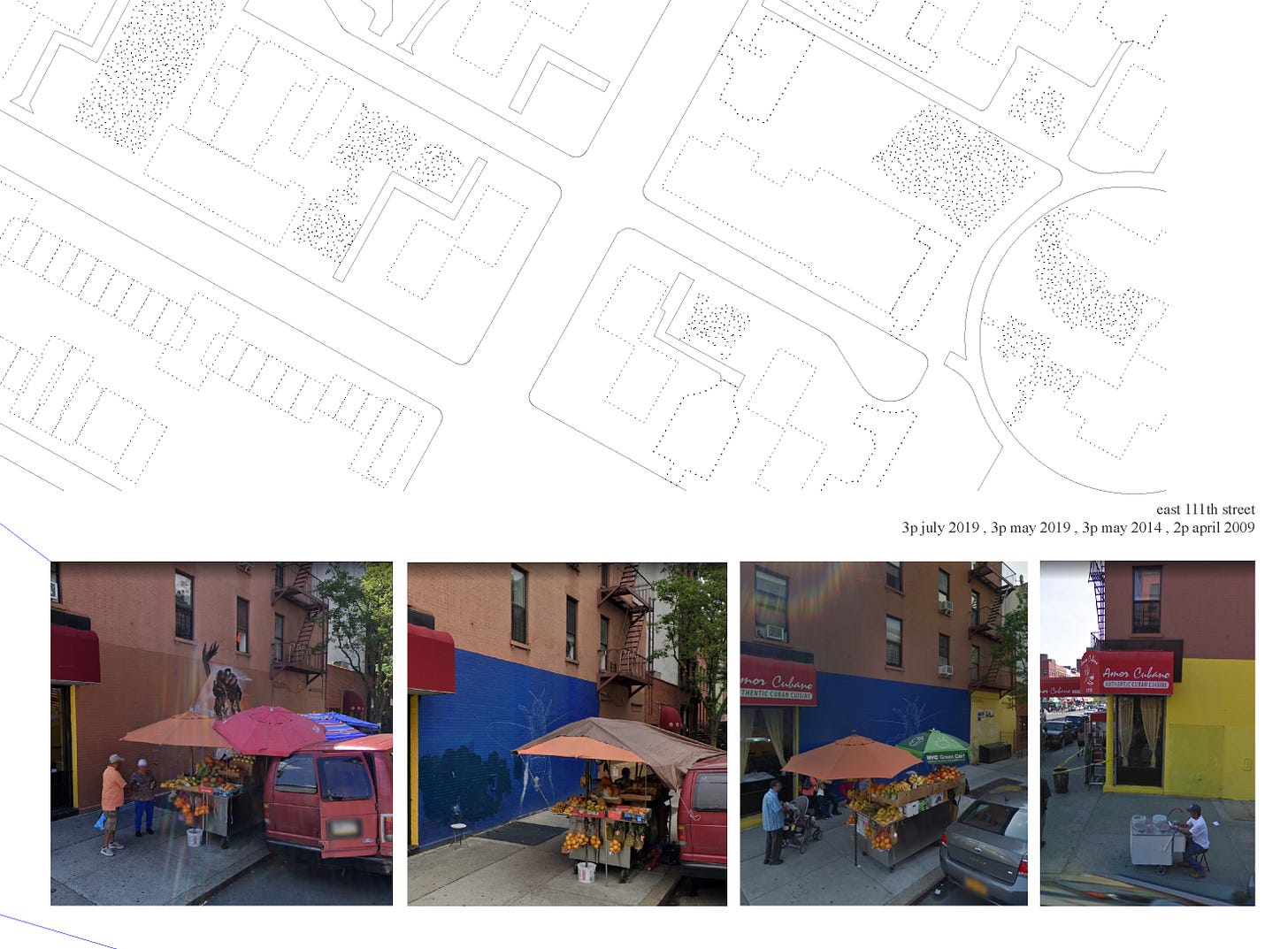

Taking cues from the presence of existing street vending operations in these neighborhoods, the interstitial kitchen serves an existing need by providing a community kitchen through city funding, with a sweat equity program and cooperative ownership model. In a case study of existing conditions in Harlem, mapped below, I track the repeat presence of vendors over the course of 10 years via google map images, indicated relative to existing community garden plots.

The four sites identified here are neighborhoods of relative food insecurity where street vendors operate regularly and require support structures. Proximity to highly trafficked subway stops is a strategic move for street vendors to sell their wares, but heightens the risk of harassment by the police since these stations are over-patrolled. This problem has gained more widespread coverage in recent years, for instance, when a woman was violently arrested and detained for selling churros in the station.16 Rather than increased policing of the populations most dependent on these services, public transit spaces should work for these individuals.

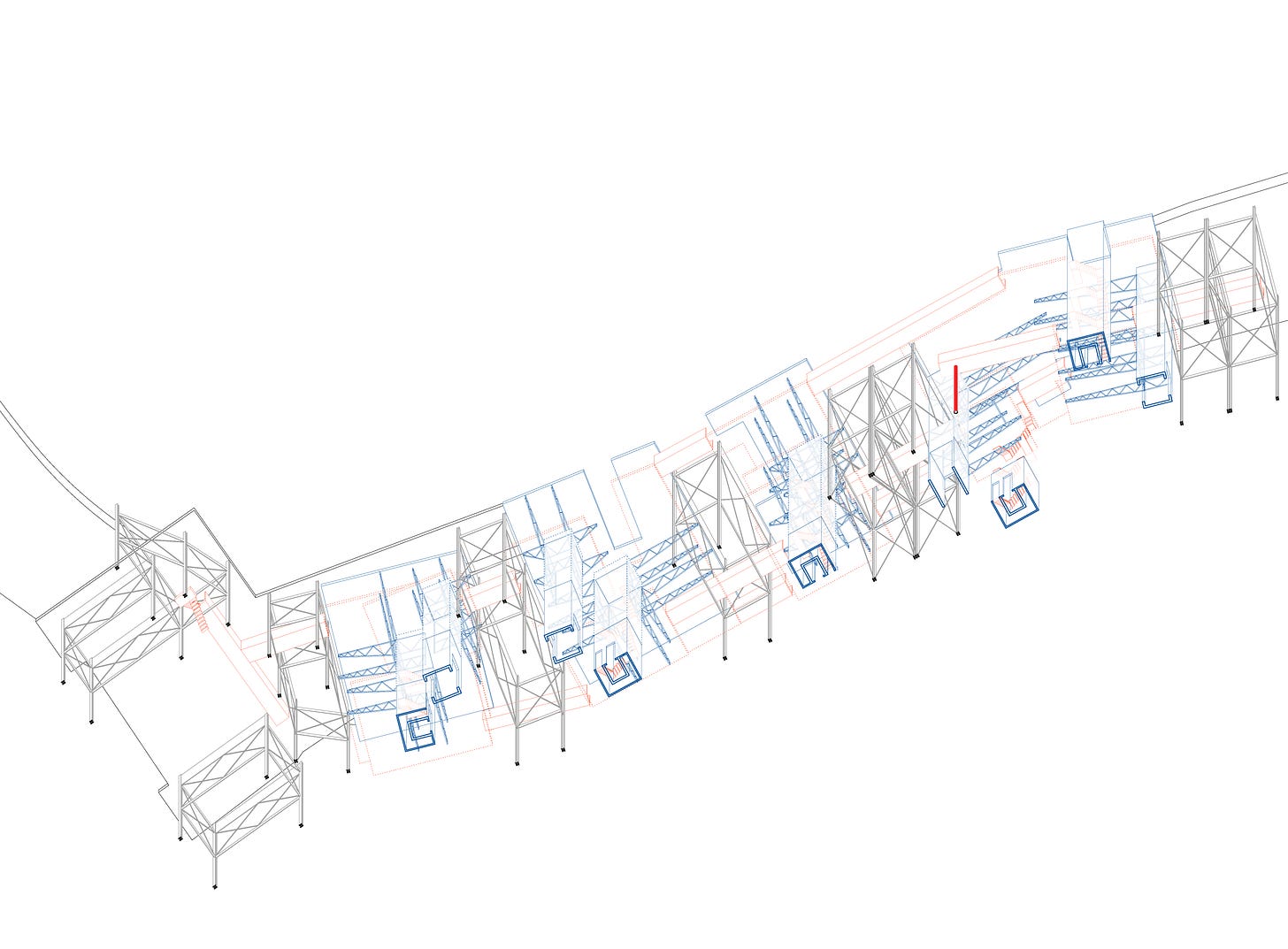

At one site in the Bronx, the existing structural supports of the elevated rail determine location of the building cores, which contain freight elevators, smaller food lifts, and stairs. The second floor is outfitted with industrial kitchen equipment accommodating 24 kitchens in total, available for singular or shared use. The building plan follows the planimetric layouts of incubator kitchen La Cocina17 in San Francisco, Hot Bread Kitchen18 in New York, and the Depanneur19 in Toronto, providing adequate space and flexible use. The third floor is occupied by hydroponic farms that service local community and street vendor needs. Access to the kitchens is tied to public transit access through the city’s subway system.

This iteration of the interstitial kitchen seeks to meet the needs of everyday New Yorkers, street vendors and their local communities, and commuters regularly using public transit, particularly those impacted by food apartheid.20 Rooted in the past two and a half years of research back in my hometown, after living elsewhere for a decade in Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, New York, New Jersey, and West Philadelphia, I’m seeking to locate the project in the specificity of Los Angeles’s public infrastructure, foodways, freeways, social and cultural fabric, in this year of the wood dragon. 恭喜发财, gong hei fat choy, happy lunar new year. “In Chinese cosmology, dragons are rivers.”21 Postcolonial astrologer Alice writes,

“Dragons started as a folk symbol for the people. This was when humanity first started living close to rivers because freshwater fertilizes the land. Only when an usurper king, one who wanted to portray himself as a man of the people, staged a coup did dragons become associated with empires. Living creatures might work to eat but we are still alive when we don’t have jobs. We just have to find another way to eat. Corporations disappear when they stop governing. Living creatures don’t issue currency but our lives don’t lose any value when our currencies change. Living creatures use unstandardized words to speak and, just by doing this, we create culture. Dragons don’t govern. They can’t really be governed either.”

Living close to the LA River for the first time these past years, learning through conversation while biking nighttime group rides, walking with groups of municipal workers, indigenous elders, university students, community organizers and activists, and local neighbors, it’s easy to understand the LA River as an infrastructural node in the potential interstitial kitchen in Los Angeles. Biking the path, I see grocery carts from nearby supermarkets scattered at the base of palm trees, in the shallow mud at the bottom of the canted concrete walls that have sought to contain the river, I see the small upright grills and makeshift cooking fires of unhoused neighbors lining the asphalt path, street vendors post up regularly under the onramps and offramps in proximity to the riverfront, with small colorful plastic stools lined up alongside carts, pots two-feet-wide in diameter steaming, grills spanning the length of a truck smoking, cases and coolers of tamales and panaderia goods stacked high. Tina Calderon of the Tongva Land Conservancy22, members of Coyotl + Macehualli who lead us through the Takaape’ Washut/Black Walnut native woodland habitat in Northeast Los Angeles23, members of the Owens River Valley Paiute24 sharing with us as settler inhabitants of so-called Los Angeles the histories of water theft by LA DWP that have resulted in the degradation of their homes and communities, teach us that these deprivations and inequities are the violences upon which our lives in Los Angeles are predicated. Any attempt at infrastructural food and transit solutions for the city have to begin rooted in understanding this historical and ongoing violence.

I am thinking, also, of Octavia Butler’s 2000 essay for Essence Magazine, that PF drops into the bookclub group chat this rainstorming Tuesday morning, in which a student asks Butler about ending the suffering in the world, and Butler states, ““I mean there’s no single answer that will solve all of our future problems. There’s no magic bullet. Instead there are thousands of answers—at least. You can be one of them if you choose to be.”25 Staying with this,26 I keep my eye trained on the tight relationship between public domesticity and transit infrastructure to envision designs for foodways made cooperative and equitable.

https://twitter.com/jjcharlesworth_/status/1316418588207648774

Mishan, Ligaya. “The Activists Working to Remake the Food System: They’re committed not just to securing better meals for everyone, but to dismantling the very structures that have long exploited both workers and consumers”. The New York Times. 19 Feb 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/19/t-magazine/food-security-activists.html

Ho, Soleil, Zahir Janmohamed, Stephanie Kuo, and Juan Ramirez. Francis Lam “Food Stories that Don’t Pay The Bills”. The Racist Sandwich. 2018. https://www.racistsandwich.com/

Bowen, Sarah, Joslyn Brenton and Sinikka Elliott. Pressure Cooker: why home cooking won’t solve our problems and what we can do about it. Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

Olmert, Michael. Kitchens, Smokehouses, and Privies: Outbuildings and the Architecture of Daily Life in the Eighteenth-century Mid-Atlantic. United Kingdom: Cornell University Press, 2009.

Evans, Robin. “Figures, Doors and Passages”. 1978.

Glasberg, Eve. “Professor Works on Projects at the Intersection of Race and Architecture: Mabel O. Wilson co-designed the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers and co-edited Race and Modern Architecture” Columbia News. 15 October 2020. web. https://news.columbia.edu/news/mabel-o-wilson-works-on-new-projects-on-race-and-architecture

Lam, Francis. “How Thomas Downing became the black Oyster king of New York”. The Oyster King and the Seagull Test.

Frame. “Thomas Downing and the Black History of American Oyster Bars.” 2022 March. https://www.framehazelpark.com/frame-stories/thomas-downing-oyster-industry-taste-the-diaspora/

Satterfield, Stephen. High On the Hog. Netflix 2021.

Ortigosa, Nuria and David Steegmann. “Interview with Carolyn Steel” Quaderns n.271: About Buildings and Food. Collegi D’Arquitectes de Catalunya COAC, Xavier Monteys. Autumn 2018. Print.

Ortigosa, Nuria. “Home Food Delivery” Quaderns n.271: About Buildings and Food. Collegi D’Arquitectes de Catalunya COAC, Xavier Monteys. Autumn 2018. Print.

Ho, Soleil. “The $200-per-person fine dining dome is America’s problems in a plastic nutshell”. San Francisco Chronicle. 11 August 2020.

https://www.streetvendor.org/

https://council.nyc.gov/data/food-equity/

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/12/nyregion/churro-lady-subway-vendors.html

https://www.lacocinasf.org/

https://hotbreadkitchen.org/

https://thedepanneur.ca/

https://www.guernicamag.com/karen-washington-its-not-a-food-desert-its-food-apartheid/

https://www.alicesparklykat.com/articles/494/2024_Yearly_Horoscopes/

https://www.atlandconservancy.com/tina

https://www.instagram.com/coyotl.macehualli/?hl=en

https://walking-water.org/2019/11/30/payahuunadu-land-of-the-flowing-water/

https://commongood.cc/reader/a-few-rules-for-predicting-the-future-by-octavia-e-butler/

https://www.dukeupress.edu/staying-with-the-trouble

i love LOVE your work! you put so much thought and your words make me think so much. thank you!!