Sometime this fall, a little kiosk outpost opens just down the street from me. When I bike Figueroa to the takeout window, I unfailingly think of this meme “life can be pretty cool because you can get a bagel. but there are also the horrors,” because I am an elder millennial brain-damaged by the internet, young enough for Facebook in high school, too old for iPhones prior to my early twenties. The kiosk is an easy caricature of neighborhood change, displacement and gentrification: the third location of a vegan and gluten-free bakery and coffeeshop located in Highland Park. Some useful temporally-specific neighborhood analogues, in my subjective estimation, would be Fishtown in 2020 Philly, Divisadero Street in 2016 San Francisco, Bushwick in 2014 Brooklyn, Temescal in the East Bay circa 2015.

I love this fennel rosemary bagel with vegan cashew herb schmear, and it’s a luxury I can afford more readily than any other time in the past half decade —grad school, a pandemic layoff, briefly subsisting on unemployment and food stamps in a new city, several moves across state lines during lockdown— to have somebody else make my morning coffee, and tip them for it adequately. In the two years since I moved back to LA, after a decade away from my hometown, I’ve never gone to the Highland Park bakery coffeeshop. Since this kiosk opened, I’ve biked that four minute ride with mortifying frequency.

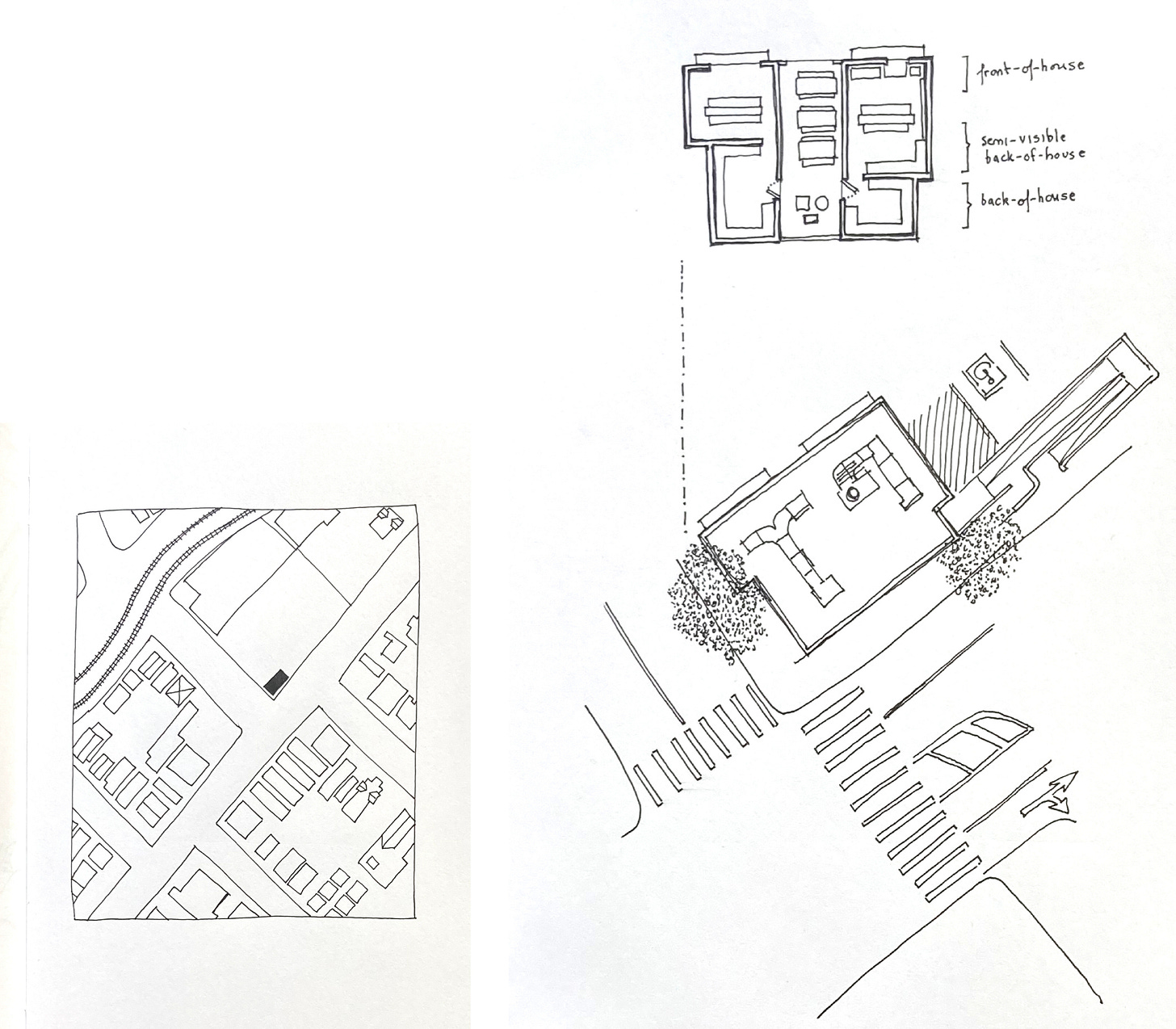

Predictably, my obsession is best explained by the spatial configuration of place. The kiosk building sits directly across from a Spanish-style bungalow court, a historic housing type that originated in early 1900s Pasadena. This Southern California style promotes neighborly behavior through front porches and shared walkways, centralized lawns and gardens; a communal aggregation of atomized structures. I regularly propose designs of this typology as a means of diversifying and densifying affordable housing on sites across LA county during this worsening housing crisis.

The parallax quality of biking past this particular bungalow court produces flickering views through its two-story arched exterior hallways. The structure frames out my regular walk with BX through Montecito Heights and Debs Park, sometimes a grey-brown mound in the distance, other times an expanse of lush green peppered with yellow mustard flowers, growing with abandon and covering the hillsides. The arched apertures encasing this view are consistent with the facade articulation of each small building, a balance of rounded and rectangular formal moves.

Across the intersection, a metal food truck casts reflective shadows into the gas station parking lot, throwing flickering geometries across the cattails growing out of fissures in the sidewalk. Short plastic stools adorn the sidewalk under the truck’s low awning. Adjacent to the kiosk building is a massive parking lot spanning between the supermarket, panaderia goods baked fresh daily and salsas made in-house, and a venue owned by an ‘Italian social organization’ that’s been in existence since 1877, a dance hall with wooden floors where ‘Queer Church of Line Dance’ Stud Country hosts formals colloquially referred to as ‘gay prom.’

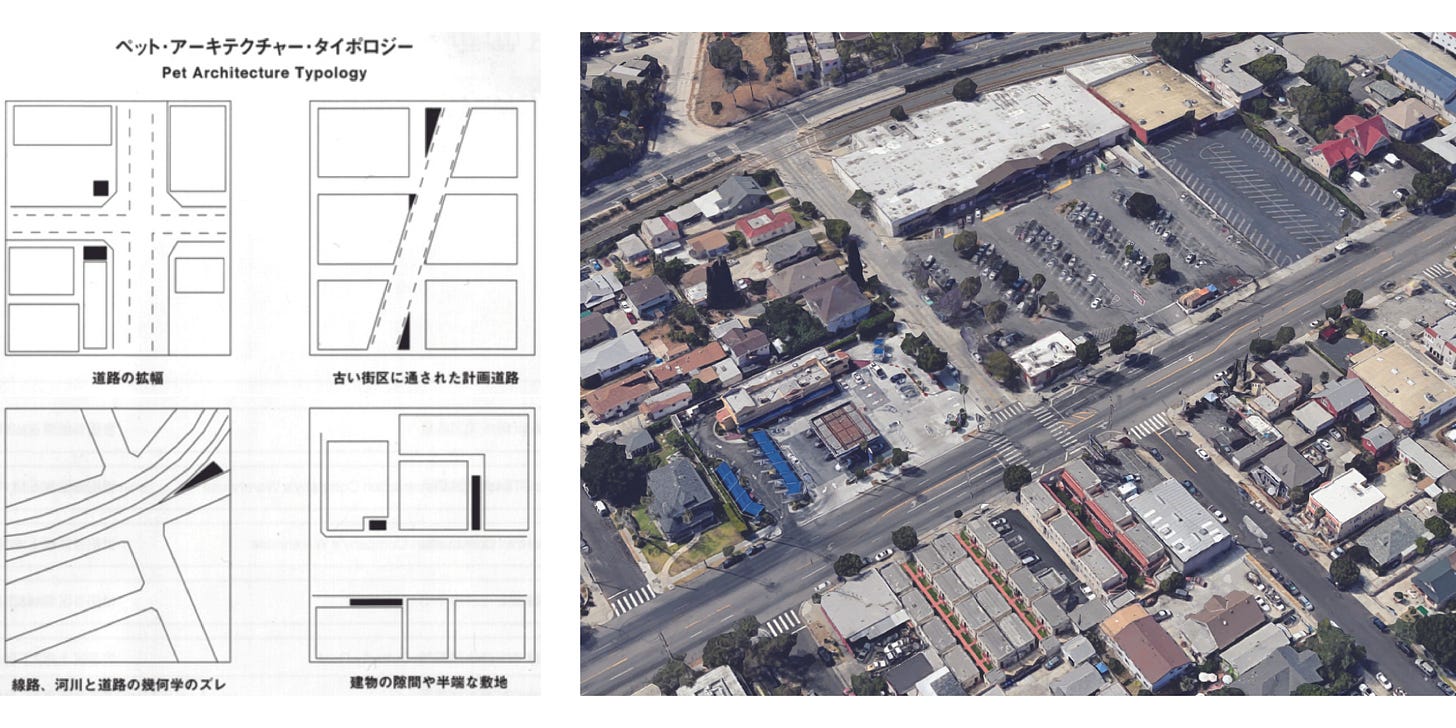

The spatial situation of the kiosk building comprises a typological instance of ‘pet architecture,’ according to the late 90s definition developed by Tokyo architecture firm Atelier Bow-Wow in their 2001 Pet Architecture Guide Book.1 Momoyo Kaijima and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto’s work as “anthropological interrogators of the city” defines pet architecture as “nuanced micro architectures,” or “very small buildings in the city.”2 A characteristic indicator of pet architecture is the use of fragmented, overlooked, leftover, or residual sites. These are often partial lots, sites that are in some way compromised, compressed, limited, or otherwise impacted by adjacent buildings, transit systems, or public infrastructures in their immediate proximity.

Ray Oldenburg’s 1989 definition of third place, which is largely the hinge of this newsletter as a project, has both sociological and spatial dimensions. Third place is a communal realm that provides space to be challenged by people different from oneself through dialogue, conflict, or conversation. This analysis points towards cafes, coffeehouses, main streets, and post offices, the sites between home and work where informality and frequent use of a given space “promotes social equity” and provides “a setting for grassroots politics.”3 Regarding the spatial dimension of third place, Tsukamoto has said,

“I learned a lot from pet architecture. They show interesting space created by occupancy. It connect two different subjectivities in architecture. One is a designer or architect's, and the other is a user or inhabitant. In 20th century these two subjectivities have been opposed to each other. Space lived by someone called the space of representation is always opposed to the representation of space , which is planned or designed by architects or urban planner. Henri Lefebvre proposed a third place. He proposed the idea of the practice of space.”4

The divide between ‘architect or designer’ and ‘user or inhabitant’ is a contrivance produced by architecture as a profession. In reality, folks are all designing their uses of and interactions with space, whether they are urban planners executing Haussmannian erasure and displacement for the development of city buildings, or unhoused folks innovating structures that range from the temporary to the semi-permanent for their own shelter. The practice of space is inherently participatory.

The kiosk building comprises two separate enclosed structures adjoined by a semi-enclosed patio at the center. One of the kiosks is “Taco Fiesta,” a 70s chain restaurant briefly bought and owned by Denny’s.5 This location has been owned and operated by Sam Sirikulbut since 1972. The kiosk to the south attracts a markedly different clientele than the kiosk to the north, connected by an interstitial zone. The interstice is a patio enclosed with a bright yellow painted metal grate, something between a restaurant’s dining patio and a side yard for garbage cans, populated casually with painted metal picnic benches and long communal tables.

Late morning today, Saturday, I talk with Richard who works at the bakery coffeeshop and is on break in the patio with all the rest of us, eating a burrito from Taco Fiesta. Two older latino uncles, one with a baseball cap and one with a cowboy hat, eat from paper bags at the front of the space; a young white man with two small, leashed dogs is stiffly poised on the park bench over his coffee and danish; a young south asian family of four joke animatedly with each other over bagels and pastries, the two young kids analyzing different tastes and flavors; an older white couple appear to have a terse but substance-less disagreement before sitting down to coffee across from each other at the other end of the long bench, overtly orchestrating a choreography of who eats what, and in what order.

Richard tells me, yeah, some families don’t eat mostly vegan, or gluten-free, so they’ll order at the burrito place next door, but maybe other family members get a bagel from us, and then they all eat together in the patio. Or, some people only come for coffee, and get food next door. Or their customers, referring to Taco Fiesta, will pass by us and just look at the sweets, they’ll come only for the sweets. Richard has lived in Covina, Pomona, but all over California, too, up north in SF, and tells me about having always passed through this neighborhood for decades. It’s constantly changing, you see the subtle changes.

Recalling the ‘get a bagel’ meme, I sometimes feel that my experience of the urban environment can be summed up by the three word phrase ‘pretty cool horrors,’ ranging from the seemingly mundane to the overtly violent. In the United States, on stolen land, there is an underlying and deep-seated horror to every aspect of the settler colonial construction of cities. And there are the encampments of unhoused folks under the freeway who I pass daily by bike, and people standing outside the 711 in the cold late at night, ostensibly waiting on someone doing a midnight toilet paper re-up to buy them a snack.

But by dint of having been born here, my embodied self retains this sense of home, this sense of place. In spite of, and due to, the covert and inescapable violence of cities, there are numerous acts of resistance and occupation, ranging in scale and scope, that register to me as ‘pretty cool.’ Unexpected juxtapositions result from the creative placemaking of individuals circumventing prohibitive urban environments and restrictions on public space.

Informal economies crop up weekly in Lincoln Heights in the form of swap meets and sidewalk markets next to the train tracks, mariachi bands occupy the public sidewalk, a big communal dinner on a plastic folding table in front of the party favor and flower store on Cypress Ave —lit up at night by string lights over a group of community elders sharing tea and comida— crops up occasionally, across the street from the stretch of sidewalk cordoned off by cones —small, declarative orange sentinels— demarcating the food distro that serves folks in the local neighborhood every wednesday mid-morning.

Here in Lincoln Heights, Cypress Park, Frogtown, Highland Park —northeast LA neighborhood names loosely stitched together from longer histories, or codified to appeal to the newcomers actively pushing out longtime residents— oral histories and anecdotes from community members reflect the pace of neighborhood change, describing both the losses of displacement and gentrification, and infrastructural gains like the county-wide initiative for fresh produce supplied to corner markets.

By design, in a country that persists on short historical memory and glorifies collective amnesia, infrastructural shifts are difficult to trace. Sara Hendren, an educator and designer who writes about how disability is constructed by the built environment, describes how the deceptively mundane design of buildings, public space, and other civic structures create disability through various design choices, normalizing and othering bodies accordingly. Of infrastructure, Hendren writes,

“That’s what infrastructure does best, after all: it performs its steady public work ideally without fanfare, only drawing attention to itself when the joints or systems break.”6

Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s conceptual art performances spanning decades, recentering the value of care work and maintenance with the workers at New York’s Department of Sanitation,7 and Agnes Varda’s observation and interaction with individuals who live on “the margins of society,” who thrive by foraging and through their efforts redesign and reconfigure place,8 are front-of-mind when I think about civic infrastructure. Beyond streetscapes, bike lanes, or public parks, the word infrastructure might denote the placemaking practices —the practice of space, per Lefebvre— of all occupants of a given neighborhood, particularly those who creatively occupy spaces deemed less desireable, overlooked, leftover, or residual.

Taking night rides on the river led by indigenous community members and organized by folks at the local bike co-op, participating in public protest and demonstrations, organizing with my local tenant union, supporting informal street food vendors and liquor stores, corner markets, and mom and pop restaurants that have persisted in this neighborhood for years, are debts that I owe to the existing infrastructure of place. In discussing pet architecture, Atelier Bow-Wow’s Tsukamoto describes the value of public space in terms of participation,

“The quality of public space is up to the peoples' participation. If all the participants are just a customer it is not a real public space. For example, in a shopping mall there are many people gathering and talking. It looks like public space, but they are just customers. They are all guests. They don't have any responsibilities to maintain the space. I think that just being in a gathering space is different from participating in the shared space with someone. We have our own programs of what public space is within our body. In the projects on micro public space we try to turn on this program by which individuals can participate in certain contexts.”9

The micro public space at the center of the kiosk building, sandwiched between two fast casual food stands, maintains an indeterminate space for the unexpected, for encounter and unplanned interaction. If the placeless quality of the public realm —space, as opposed to place— can largely be attributed to the incessant buying and selling of wares as the sole motivator for communing in meatspace, then a practice in placemaking requires engagement and interaction beyond the merely transactional, beyond a belief in debts owed.

I bike my neighborhood of the past thirteen months documenting various social and spatial infrastructures, taking note of interstitial anomalies. One night in late October I pass four taco stands, two that I frequent and two that I don’t, biking back from the climbing gym under an enormous full moon —the blood moon, the hunter’s moon— sitting bright on top of the 5 and casting shadows off the side of the freeway, shadows feathered on shadows, pushing forwards. A family is throwing a backyard party, boisterous reggaeton floating up into the late autumn air. I pass a gas station, a restaurant, a bakery by the corner bus stop, the intersection where I always yell at delivery truck drivers from my bike to get the hell off their phones, and sometimes an uncle standing at the street corner will chime in and cheer me on, admonishing them. The orange-lit sloping street that sulks behind a towering curtain of dark trees, the glass in the bike lane, the guys at my favorite spot “–burrito vegetariano?” they ask without needing an answer. “Queso?” “Con todo.” “Salsa?” “Los dos!” This is still the extent of my poorly-accented Spanish tonight, Wednesday, biking up to the same stand again for their nopales pico de gallo, documenting urban detritus and pavement paraphernalia on the way, ‘pretty cool horrors’ added to the archive.

Bald, Sunil. 21 April 2019. “Atelier Bow-Wow interviewed by Sunil Bald.” Bomb Magazine. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/atelier-bow-wow/

White, Mason. May 2022. “Atelier Bow-Wow: Tokyo Anatomy.” Archinect. https://archinect.com/features/article/56468/atelier-bow-wow-tokyo-anatomy

Oldenburg, Ray. 1989. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through the Day. Paragon House.

White, 2022.

Elliott, Farley. 1 March 2016. “Taco Fiesta Serves Delightful Hard-Shelled Nostalgia in Highland Park: It’s the hard shelled taco destination of your dreams.” Eater Los Angeles, Dining on a Dime. https://la.eater.com/2016/3/1/11117302/taco-fiesta-highland-park-los-angeles

Hendren, Sara. 2020. What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World. Print. p201.

Steinhauer, Jillian. 2017 February 10. “How Mierle Laderman Ukeles Turned Maintenance Work into Art: Best known as the artist in residence at New York City’s Department of Sanitation, the septuagenarian Ukeles is having her first full retrospective, at the Queens Museum.” Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/355255/how-mierle-laderman-ukeles-turned-maintenance-work-into-art/

Agnès Varda. 2000, France. The Gleaners and I. https://www.criterion.com/films/30368-the-gleaners-and-i

White, 2022.