Interstitial Kitchen

Sanctuary Sites

I bike and walk the streets of Bangkok and Chiang Mai alone in late summer 2018, night air bearing down heavy and humid, the grooves in these borrowed bike tires worn through before I got here. Just like back home in New York and LA, it is always the presence of vendors keeping these streets safe at night: the ambient prospect of a warm meal, the physical proximity of the hands making it, relationships between generations visible in the laugh lines on people’s faces and in their physical gestures, calling out to each other from tents and tarps propped up by open car doors and fastened to traffic signs, string lights looping across the open space of the sidewalk.

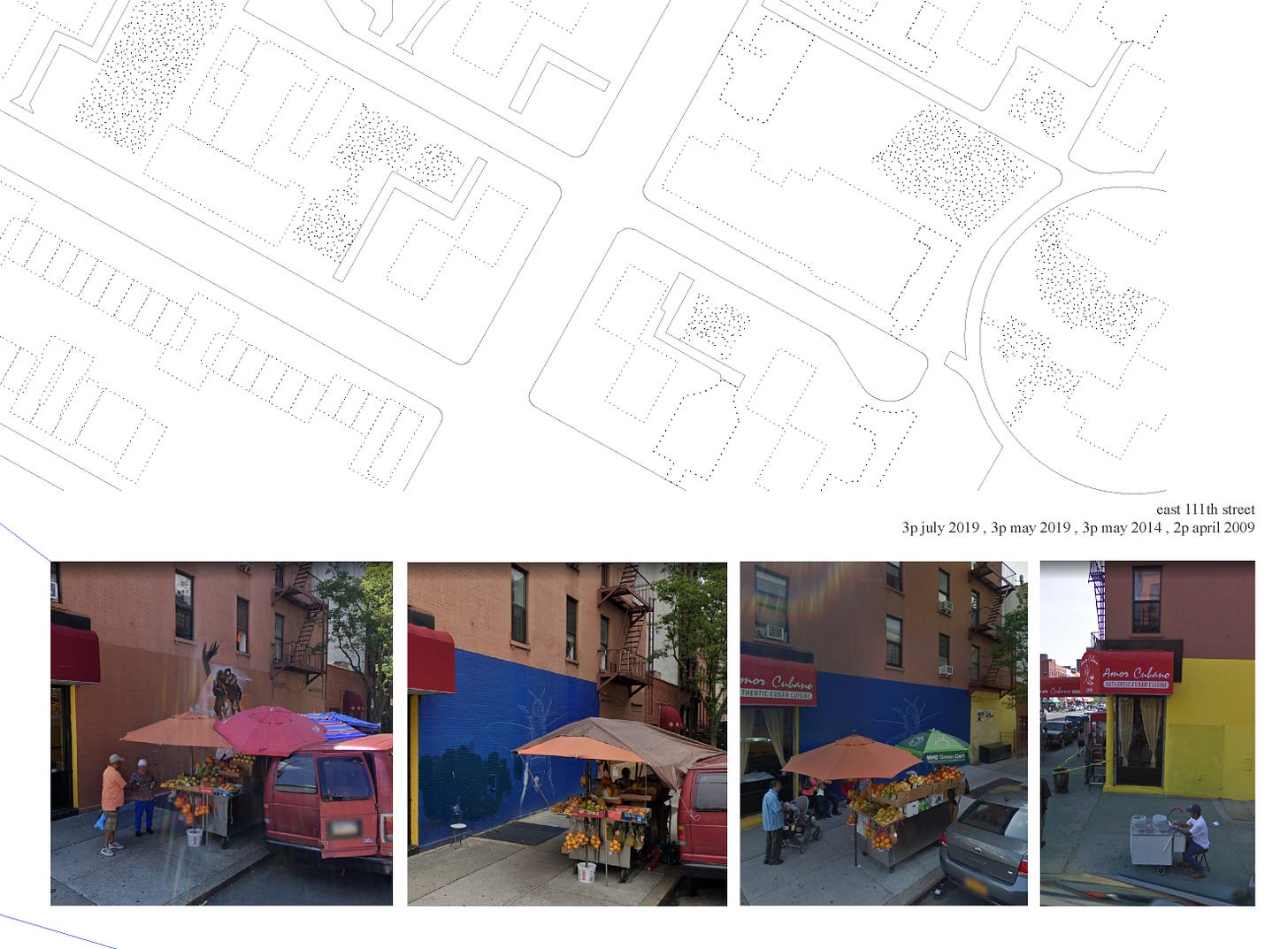

Back home, I read a report from the Urban Justice Center surveying street vendors across Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx that identifies food apartheid—defined by the absence of grocery stores, amenities, and public transit—in neighborhoods where street vending proliferates. The Street Vendor Project, the organization that authored the report, protects vendors from fines and citations, defending a livelihood that is already precarious, reliant on the day-to-day cadence of other people’s schedules and movements, requiring a great deal of labor for relatively little pay. Street vendors provide the most publicly accessible third place in the city and create the safest public spaces with their adaptive spatial strategies—moveable plastic seats, communal kitchen tables, mobile grills and freezers.

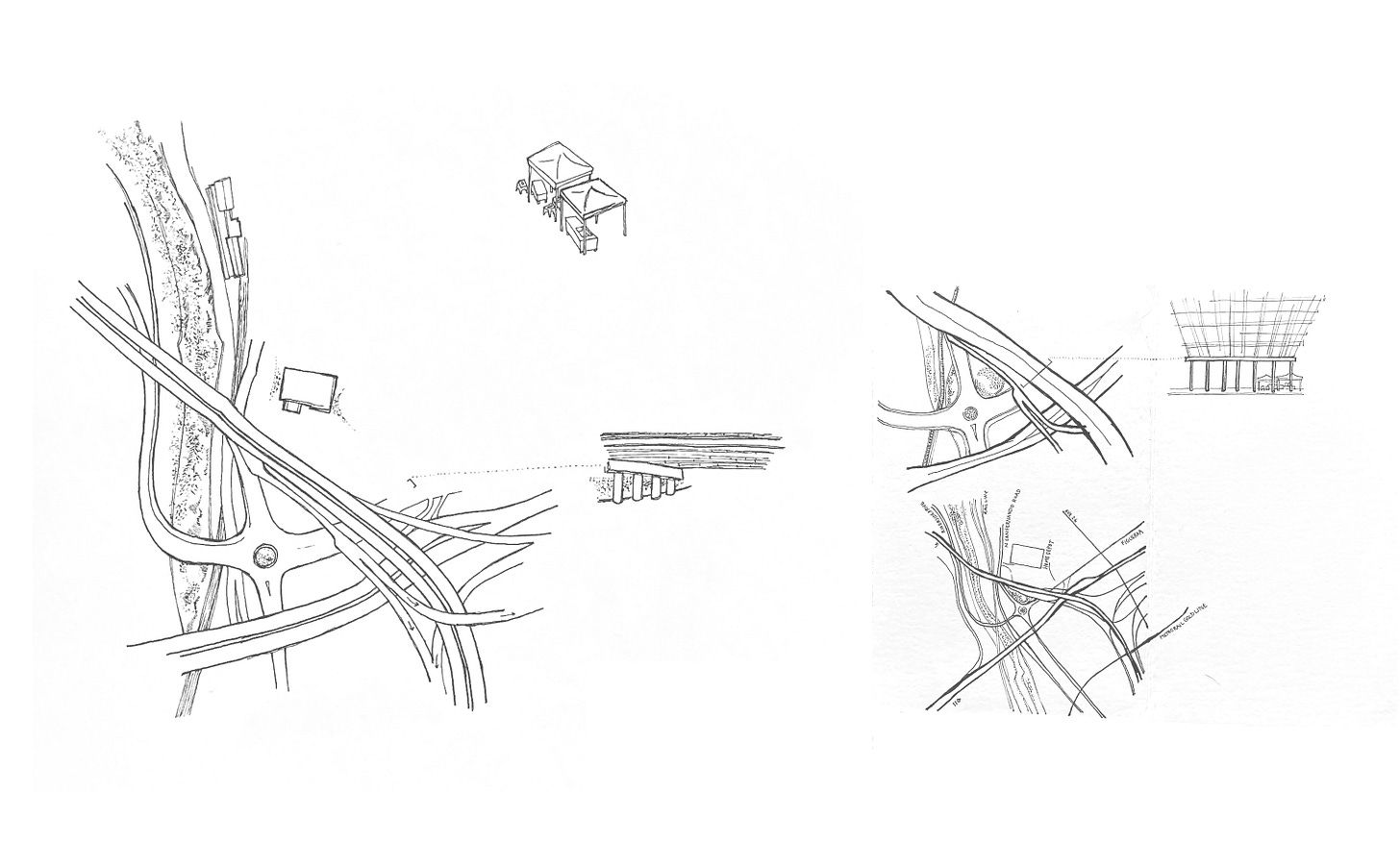

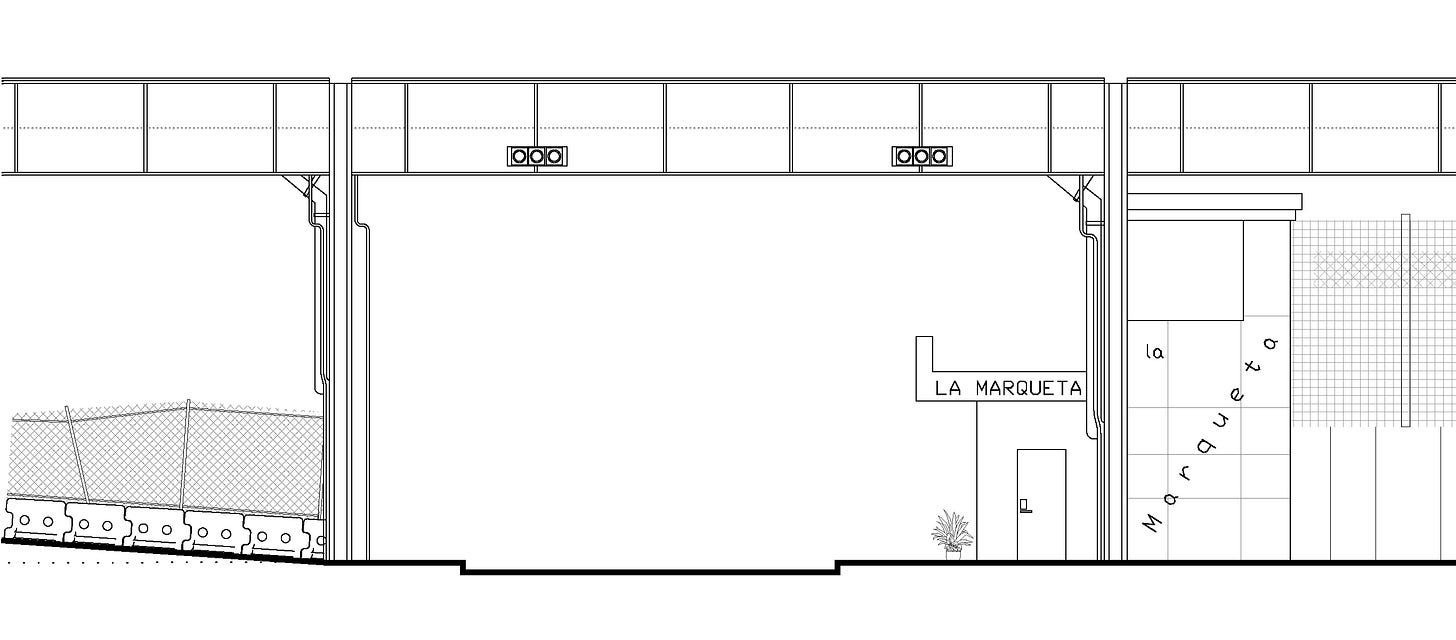

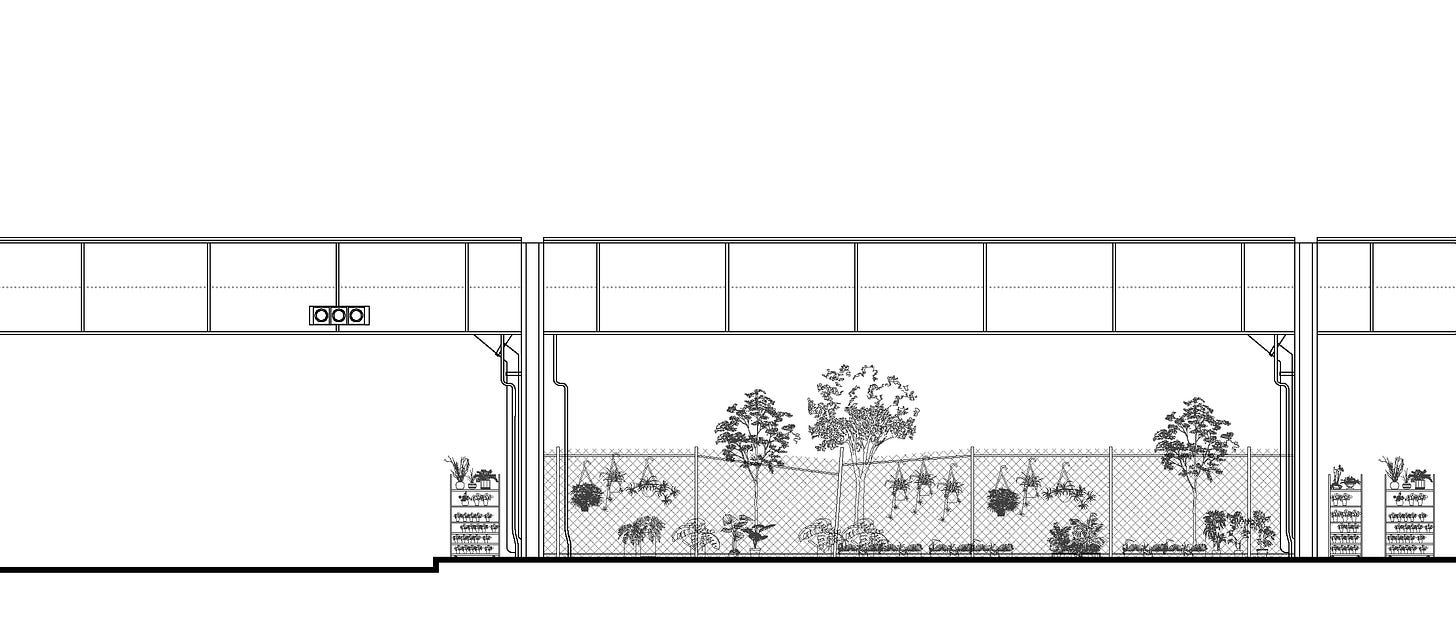

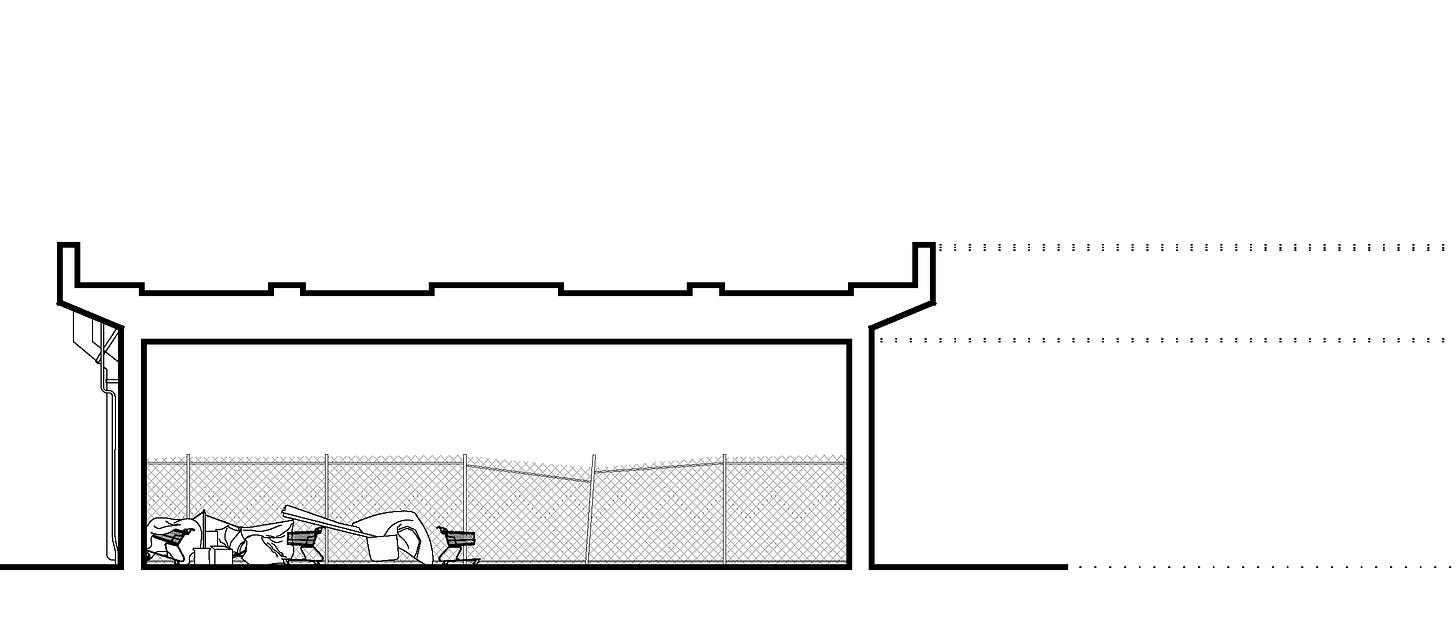

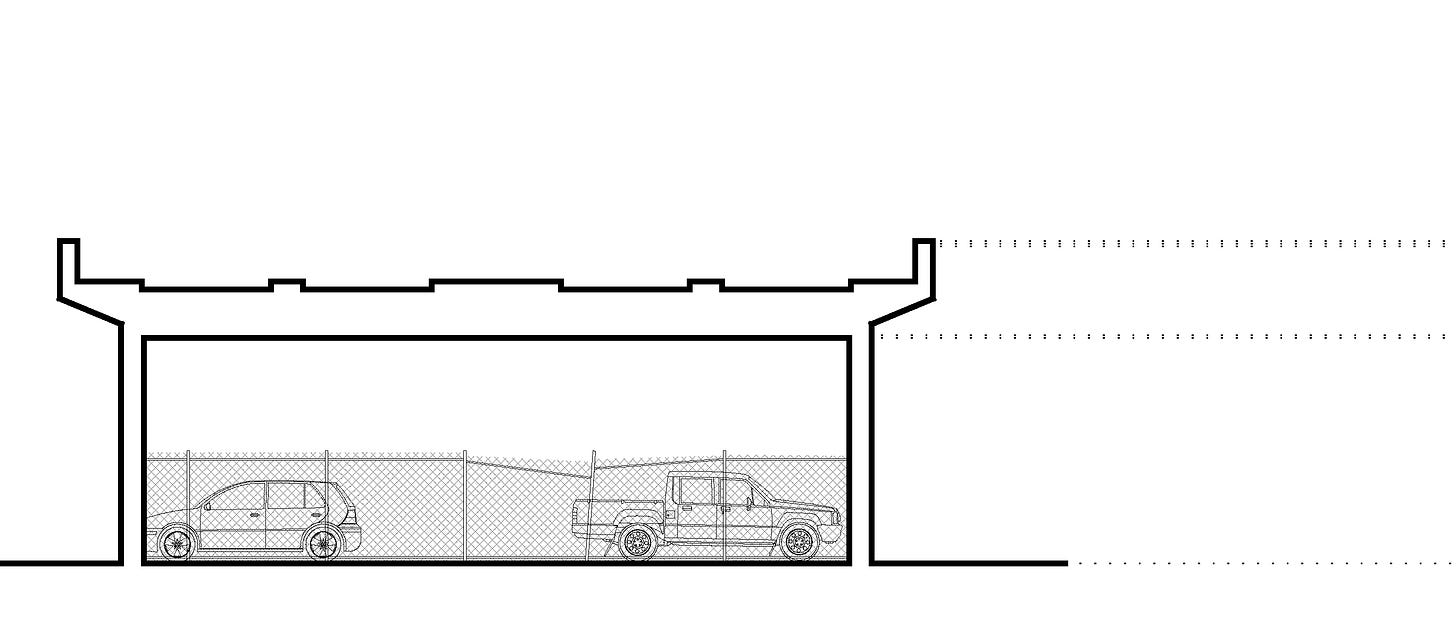

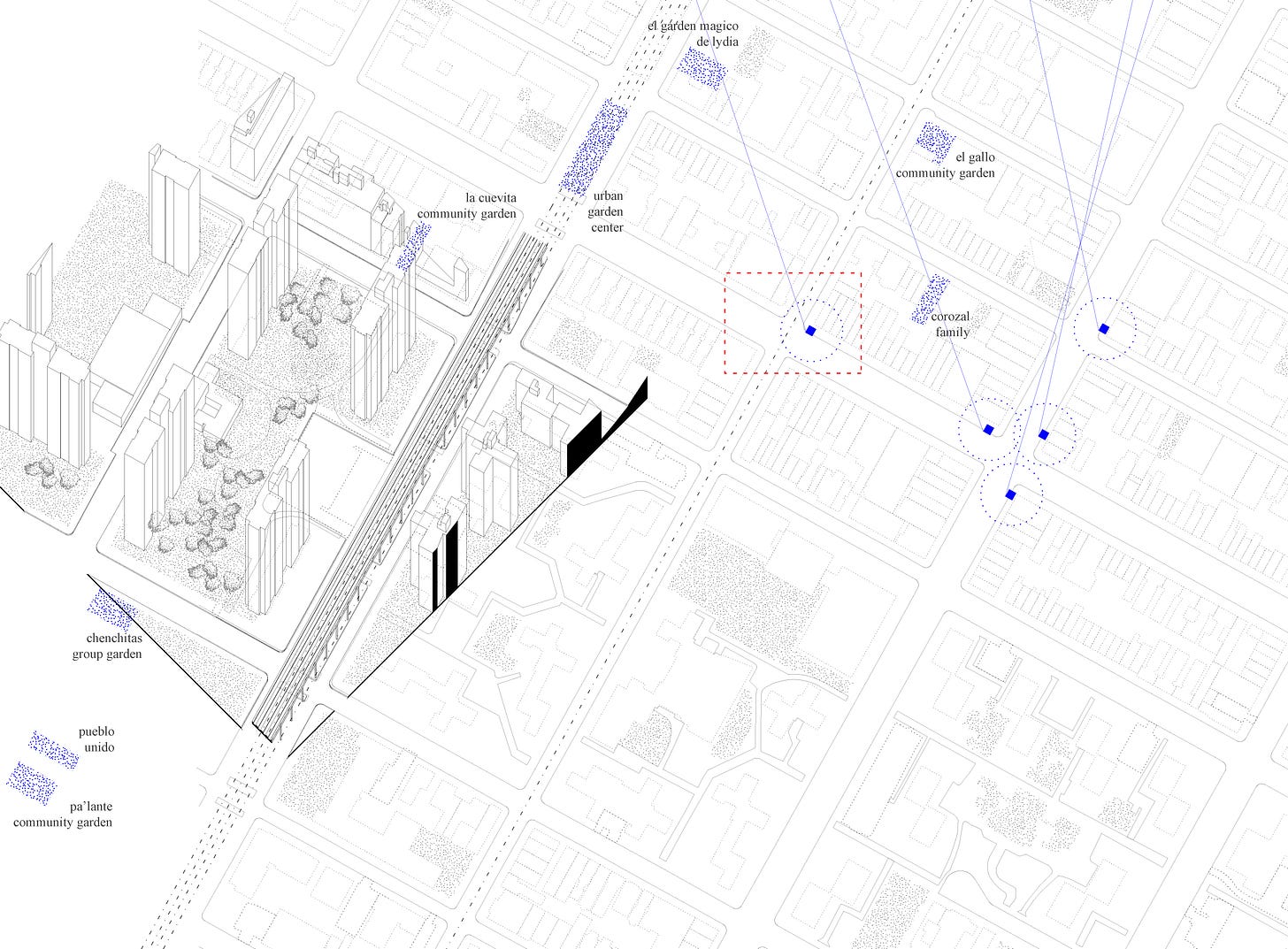

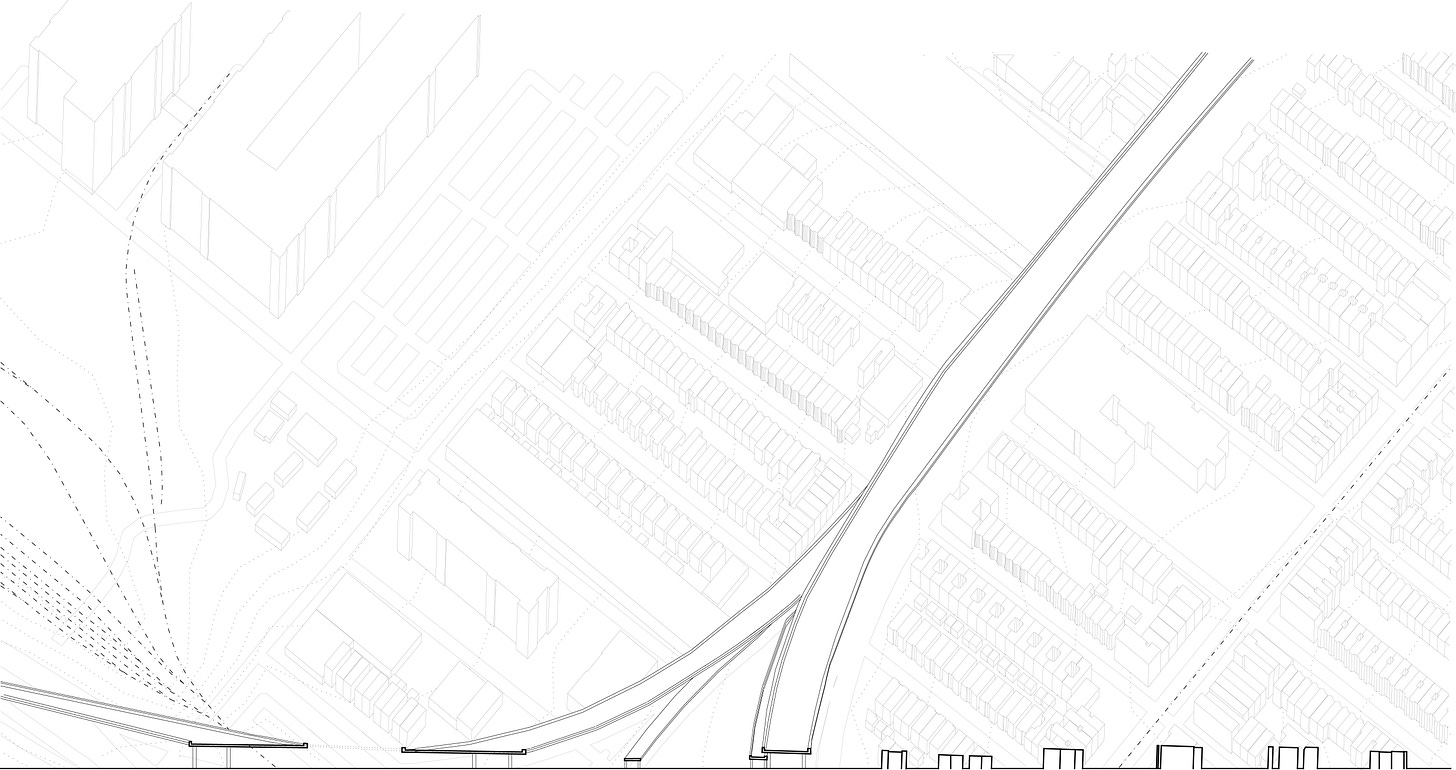

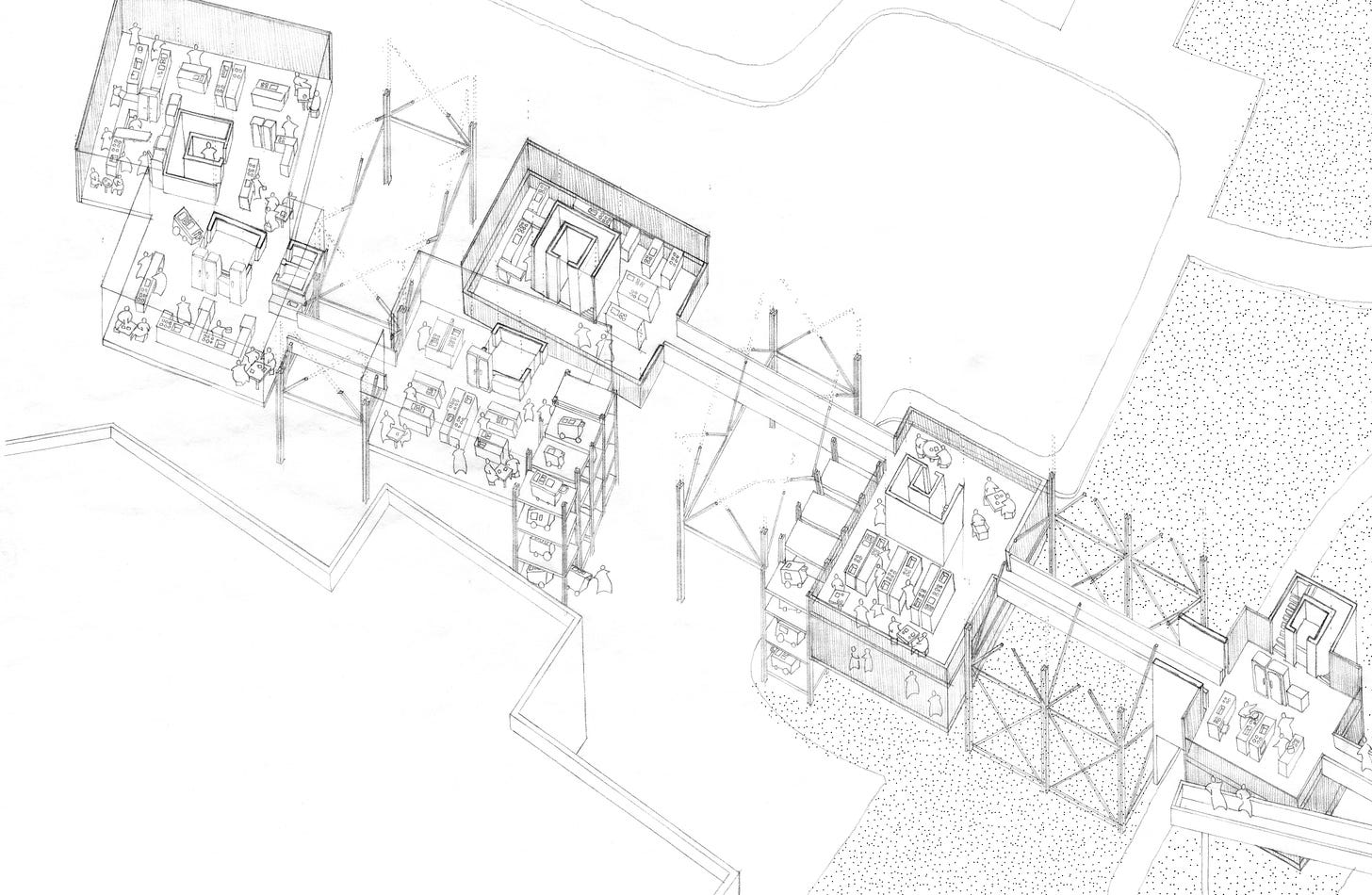

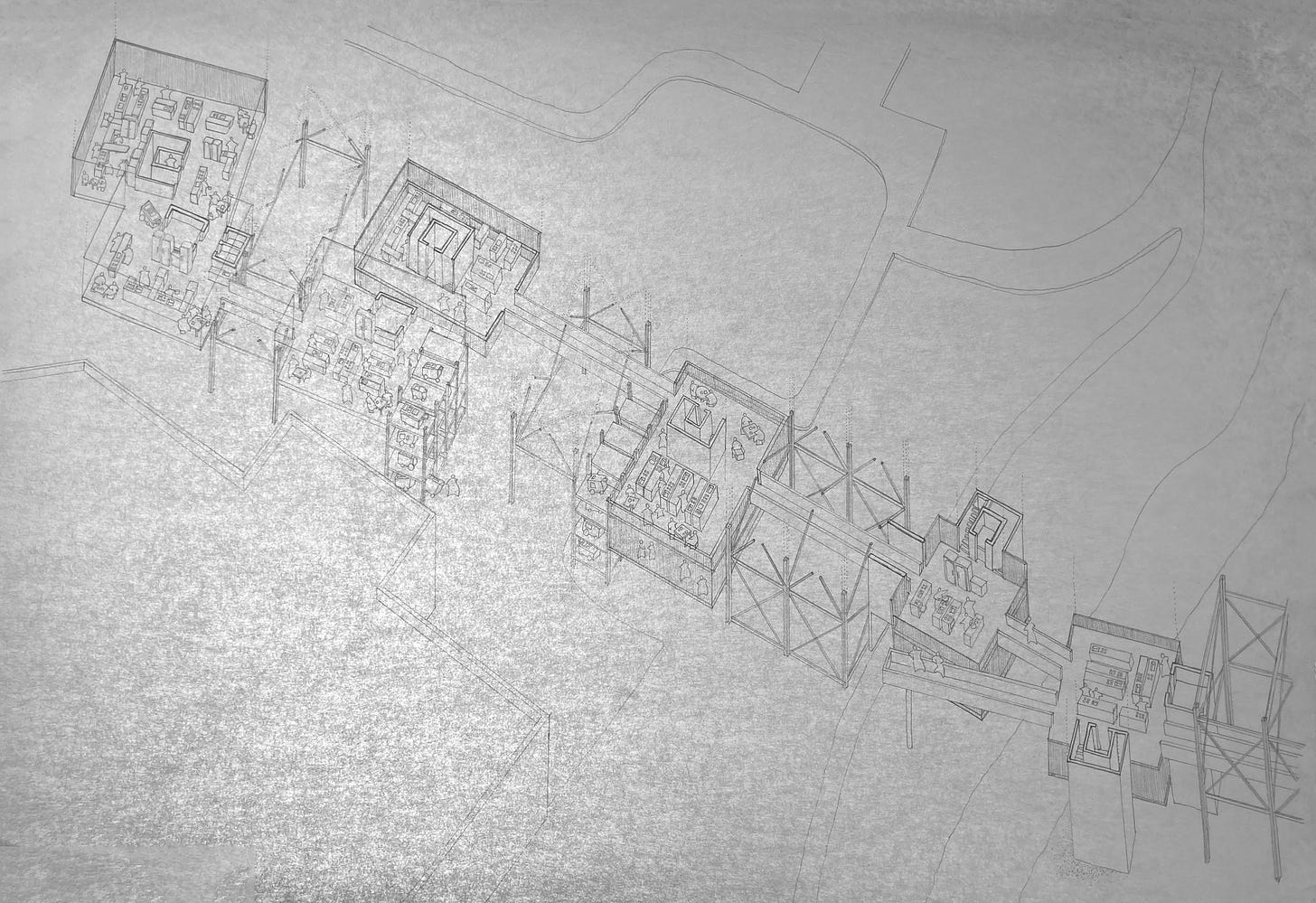

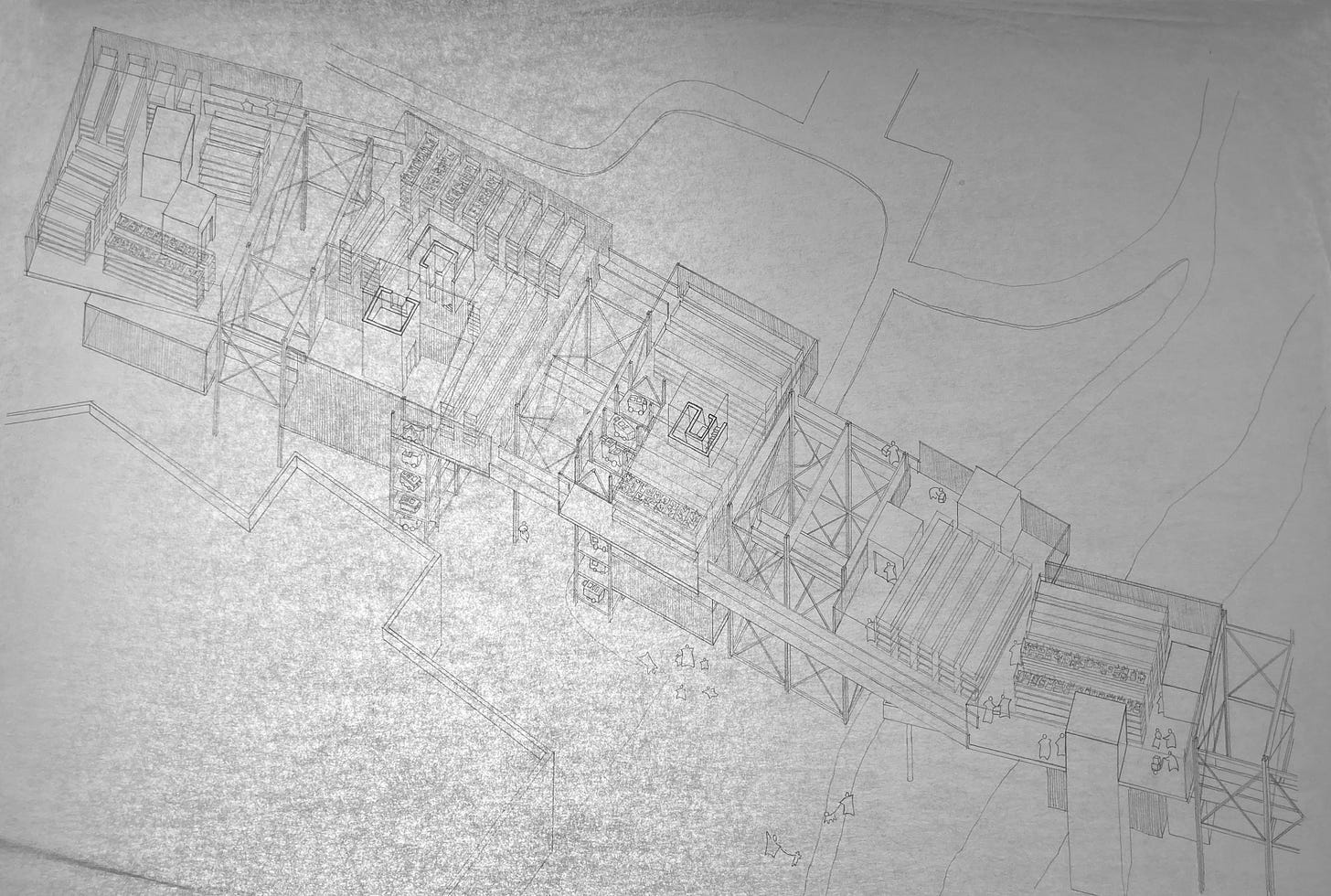

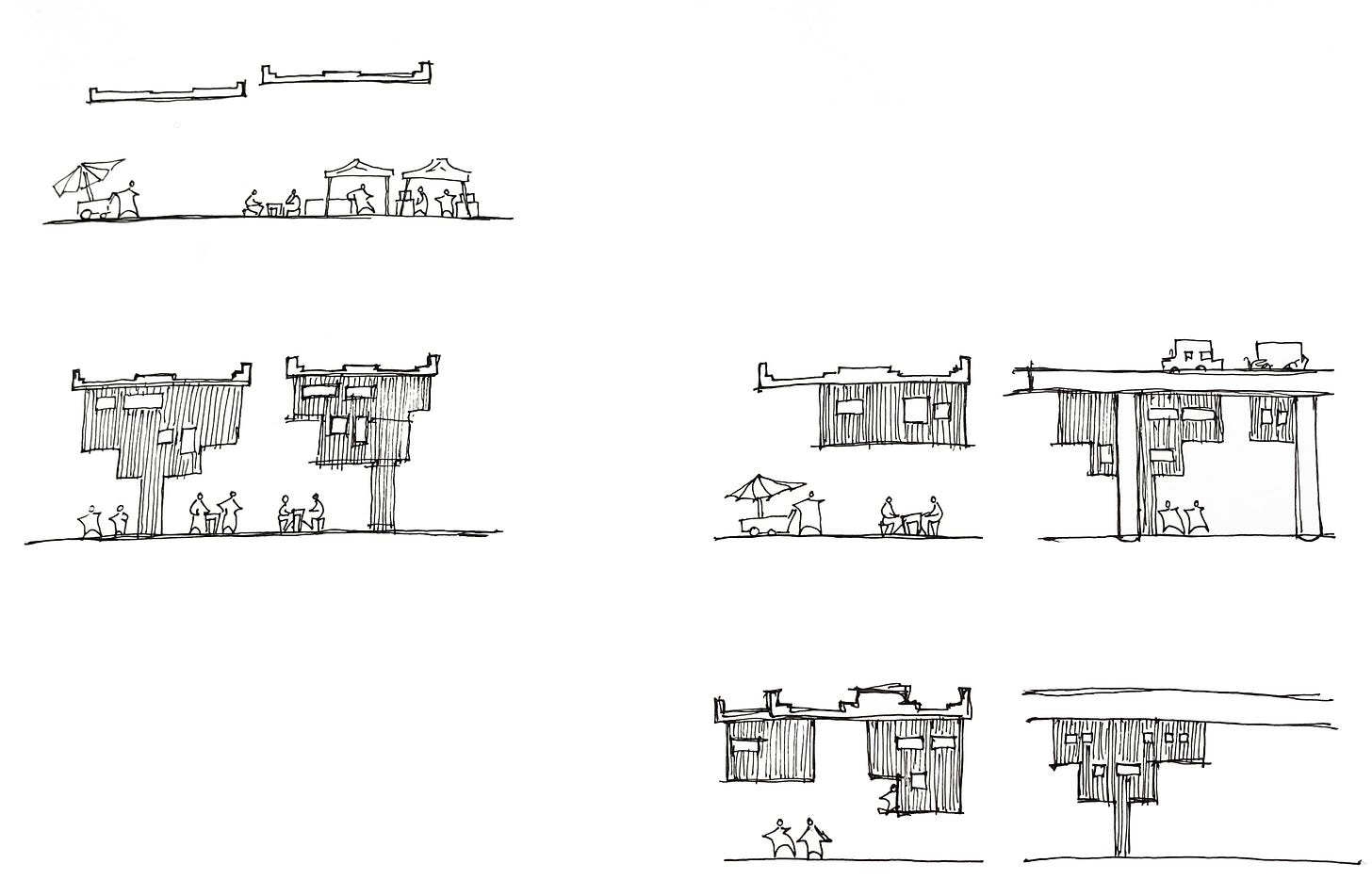

Partly inspired by the absurdity of mechanized parking lifts that I see while biking around New York, cars stacked in vertical storage in a city where it is almost always more expedient to bike, walk, or take the metro, I design a structure with half-size lifts for food carts and stalls. The lifts would provide affordable overnight parking for vendors and connection between the ground outside and public-access community kitchens with industrial cooking equipment. These structures are part of a city-wide initiative to build communal kitchens, hydroponic farms, and storage space directly accessible from metro stations, convenient for vendors who commute from or sell at dispersed locations all over the city. Access is premised on a sweat-equity model, where anyone can book time in the shared kitchens and pay it forward with cleaning tasks, contributing to the maintenance and upkeep of the space. Because these structures occupy marginal space, underutilized or overlooked vacant lots under elevated metro lines and train tracks, I call it the interstitial kitchen.

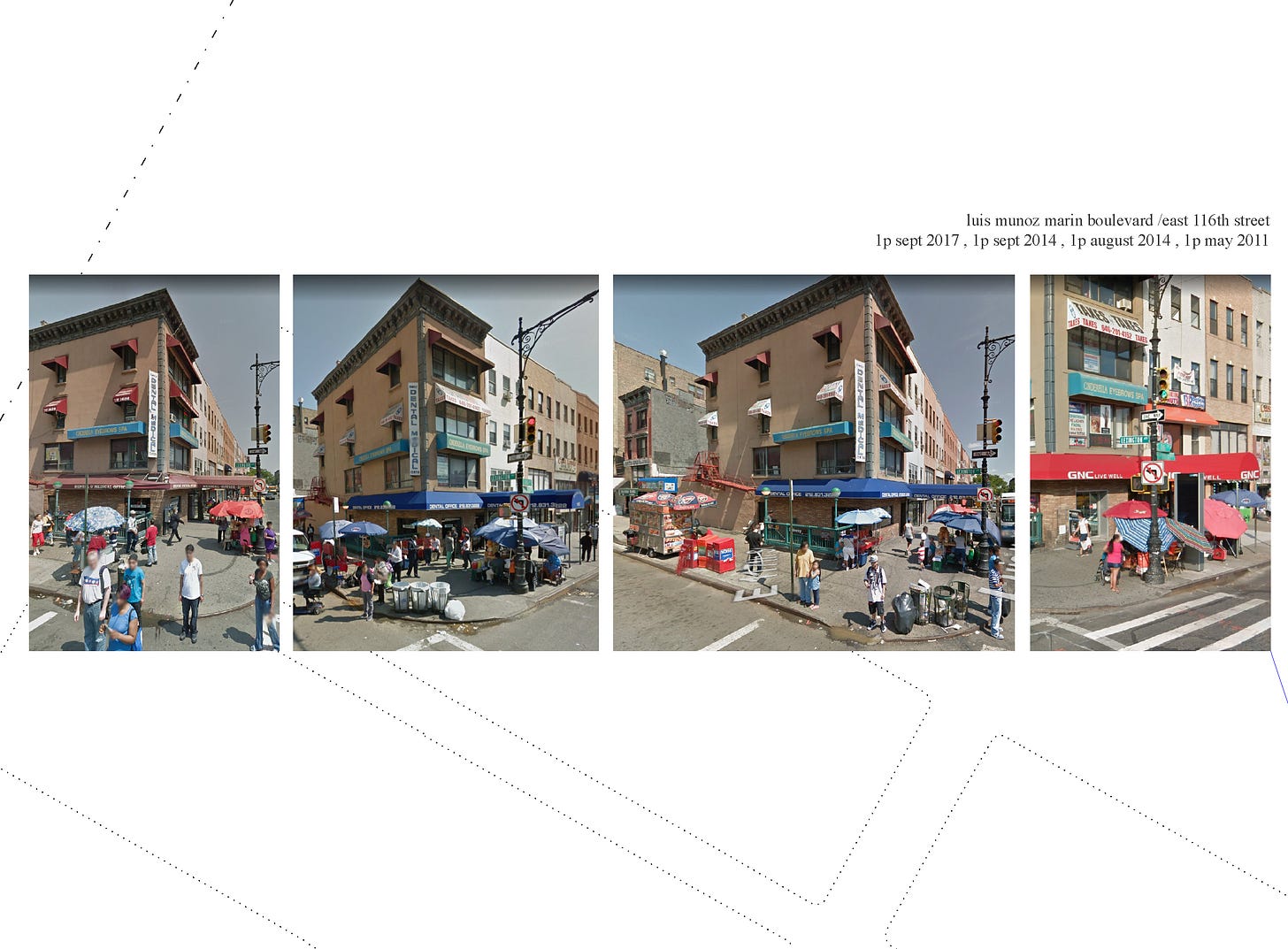

In New York, I map community gardens, public parks, multi-family housing, and metro stations relative to where street vendors regularly congregate, locating sites where an interstitial kitchen could provide for a preexisting need. These past four years since moving back to LA, I draw out maps from the bike lane, tracing possible sites while I’m out running errands, biking to the laundromat, biking the river, biking home from the grocery store or corner market. Last night meeting with our local of the Tenants Union, we recognize thirty days of organized patrols out of centros at Cypress Park, Macarthur Park, East Hollywood, built out quickly through preexisting networks of tenant organizers coordinating with local worker centers. These past thirty days, especially, I think about the risks and dangers of mapping, how legibility is weaponized by institutions and governments, the threat of state surveillance; what are our best practices for using maps to shape our work while keeping each other safe?

Like the Bronx site, I locate a site in LA close to the river—a parking lot under a tangle of freeways that I bike every day. A church often meets in the lot sunday mornings, a sea of white plastic folding chairs and an enormous pair of speakers that I can hear praising Dios in a booming voice clear across the train tracks, over the river, from the highway. We hold asambleas and organizing meetings there, too, recalling how crucial the encampments were as a physical place for us to gather, strategize, share resources and provide political education. These residual spaces under freeways are evidence of the historic redlining and ongoing displacement that breaks up our neighborhoods and cuts through the existing urban fabric. Like our centros and community patrols, like the student encampments and people in the streets fighting for a free Palestine, we occupy these marginal or overlooked spaces to stitch across these broken places and forge old and new connections.

In house meetings, over dinners of vegetarian curries and enormous flatbreads the size of our torsos shared communally, out at local restaurants with a shared plate of pan dulce between us, or at a vigil in the neighborhood with the brown paper box of pan dulce passed between us, in the community garden, biking the streets, sitting on the river down close to the water, we speculate about what comes next. How do the centros become something sustainable, how do we develop these patrols into regular habits and practices in the safekeeping of our neighbors, with less militaristic severity, but no less militant in our regard for one another? When we aren’t on the defensive, in a perpetual state of response and reaction, how do we keep this same momentum and scale up, building out relationships with our neighbors, constructing a bigger tent, organizing our priorities and demands, strategizing together and refining our tactics in support of the future we want for our city?

In a telling anecdote from one Home Depot parking lot near Alhambra weeks ago, self-proclaimed community defense volunteers had not spoken with the jornaleros, introduced themselves, or asked how they could help. Leaning on preexisting relationships, the jornaleros called in tenant organizers to check out the situation, who were these suspicious people hanging around with walkie talkies? When several locals of the Tenants Union convene under canopies with picnic blankets and pizza sunday afternoon, we are sign painting for upcoming court support dates, strategizing around the call for an eviction moratorium and general strike, and more immediately, around the end of the temporary restraining order this coming friday, what that might mean for our centros. We underscore the importance of relationships between community members, conversations between vendors, laborers, and neighbors that are continual—consistency, regularity, and repetition the key for building trust and durability.

The vendor buy-outs spring up from relationships between vendors and neighbors—Ktown for All and CCED lead efforts in Ktown and Chinatown; other local campaigns support vendors in Eagle Rock, Lincoln Heights, Echo Park; Pasadena for All, the AETNA Street Solidarity project, South Bay for All organize funds. Another campaign focuses on the lost wages of landscape construction and maintenance workers, another supports day laborers. Online, these relationships are often abstracted whereas in-person, they are materialized. In recent weeks, we begin planning a vendor buy-out and swap-meet in Cypress Park, offering our skills as artists and musicians, materials like food or fabric, clothing, medicine, and other supplies, relationships with vendors and unhoused community members, to contribute to this effort; please reach out to build with us.

Two days prior, the LA Tenants Union celebrates ten years of organizing across the city. Yesterday, AETNA Street Solidarity celebrates one year of really really free markets in Van Nuys. Learning from their example, the principles are simple.

FREE food, clothing, and more. Todo gratis.

Comida, ropa, y más. Come as you are.

Give what you can. Take what you need.

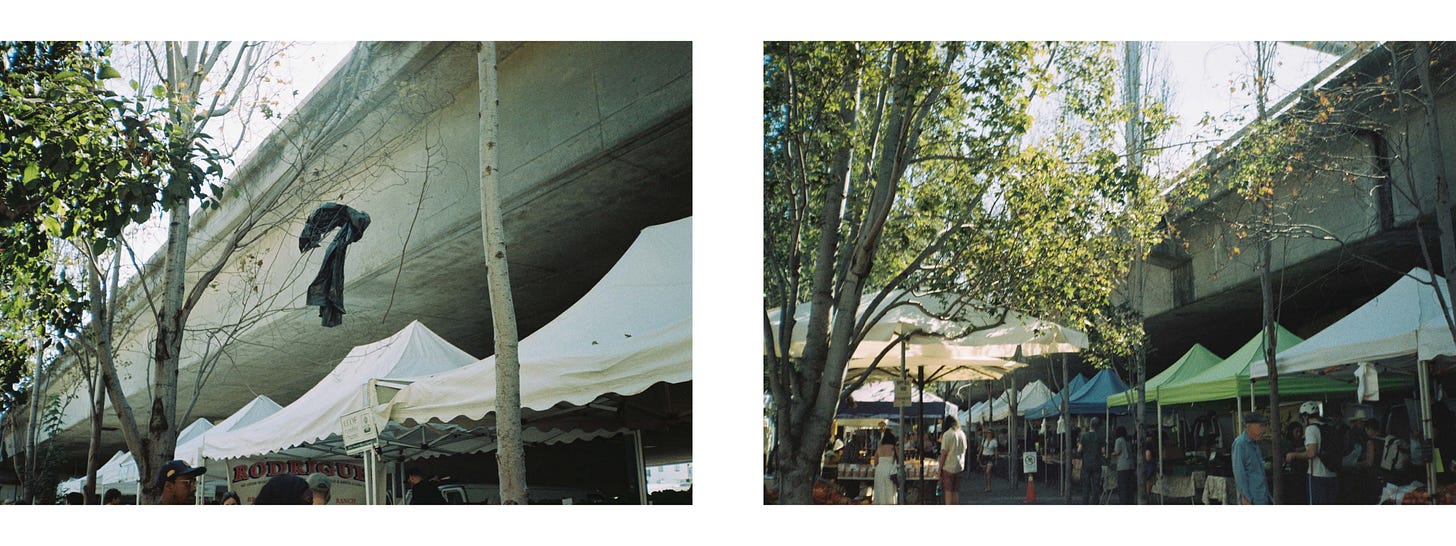

At a clothing swap we’ve regularly convened for four years now, first at the beach and a public park, then recurring always at the same spot down on the river, on the slab under the 2 freeway near Gilroy Street, we strive toward the public rather than the private, congregating not in homes or yards, but meeting each other instead in the accessible and residual open spaces of the city. Sometimes, there is an encampment built out under the freeway. We keep a respectful distance from people’s homes, or talk with the woman who has three chihuahuas that come running up to us. There’s a troublemaker who likes to lay out tacks, spike-up, to catch our bike tires as we ride along the river path. Cleverly-constructed wooden platforms sometimes extend from the metal railings, tents strung up that overlook the river.

Everyone contributing time and resources toward the really really free market in Van Nuys, the commitment to language justice in organizing spaces where Spanish- and English-speaking renters build solidarity every week, inspire me toward connection, forcefully remind me to make a better effort at communicating with the frutero down the street, who I bike past daily, and the pupuseria popping up under a tent at the corner market on my block. Regardless of language barriers, we need these relationships, to tie ourselves to each other during this crisis and before the next one. In one meeting last week, I stifle a laugh while marking down someone’s offhand comment, “it’ll always be a balance between a highly-vetted high-security chat that doesn’t do much, and a chat with lots of people in it that …does something.”

In church, there is a culture of meetings, a tradition of assembly around shared beliefs, convictions, and ideals. The encampments, beyond building barricades that advanced on learnings from occupy and other movements, provided spaciousness to gather, to process, to think together, to grieve, to strategize. I think about camping out in the forests, mountains, and desert, surrounded by enough space to make us feel small, interconnected and interdependent. The dissolution of contrived boundaries provides a fragmented roadmap for reciprocity, toward public domesticity, shared resources, property, and materials in the construction of a place between us. Camping out in the underutilized lots and marginal spaces of the city, as a form of protest, mirrors the strategies of our unhoused neighbors, who insist on “learning the skills that we need to make home ourselves.” As we materially insist on making our lives more permeable to one another, striving toward a practice of public domesticity, I envision and draw plans for physical structures and buildings that would do the same.

I love this. Visionary and grounded at the same time. In the community where I live (a medium sized city in south-western Ontario, Canada) we don't have street vendors at all. The regulations are so stringent that only food truck operators are allowed to sell food on the street. And aside from encampments of unhoused people - who are criminalized by a recent bylaw and constantly threatened with eviction - no one is occupying marginalized spaces because of the stringent regulations prohibiting "loitering." As a result, we are completely missing even the vision that another way is possible.