a version of this text was originally edited and published with pidgin press in spring 2020

A grassroots movement is quietly sweeping Japan. Children’s cafeterias offering free or low-priced meals, known as kodomo shokudō, are opening to alleviate childhood poverty and food insecurity at the scale of local communities. By April 2018 there were 2,286 kodomo shokudō operating nationally, up from 317 in May 2016.1

Aya Kimura, professor of women’s studies and author of Hidden Hunger: Gender and the Politics of Smarter Foods, describes kodomo shokudō as “different from food banks in that they serve cooked meals directly to individuals rather than providing foods to be used at home or in institutions.” Unlike soup kitchens, the shokudō do not have an exclusive focus on the poor but are open to anyone, charge a small fee (US $1-5), and are “focused more on creating a space (ibasho) for people with various challenges including but not limited to food insecurity.”2 Working against an isolating culture of overwork and stigmatization of poverty, the kodomo shokudō as ibasho provides an accessible third place between home and work, a safe space for children and their families. Men and women in Japan commonly work inordinately long workdays, and for some parents the shokudō operate as a childcare service in addition to cafeteria and community center.

Though a national phenomenon, individual kodomo shokudō operate independently, bound together by no more than a common ethos. Kimura cites the Japanese conception of mottainai, translated roughly to “not being wasteful,” as intrinsic to their project. In the kitchens, this broader moral outlook is channeled into daily practice, where bulk purchase and food production allows waste to be minimized and communal benefits to be maximized.

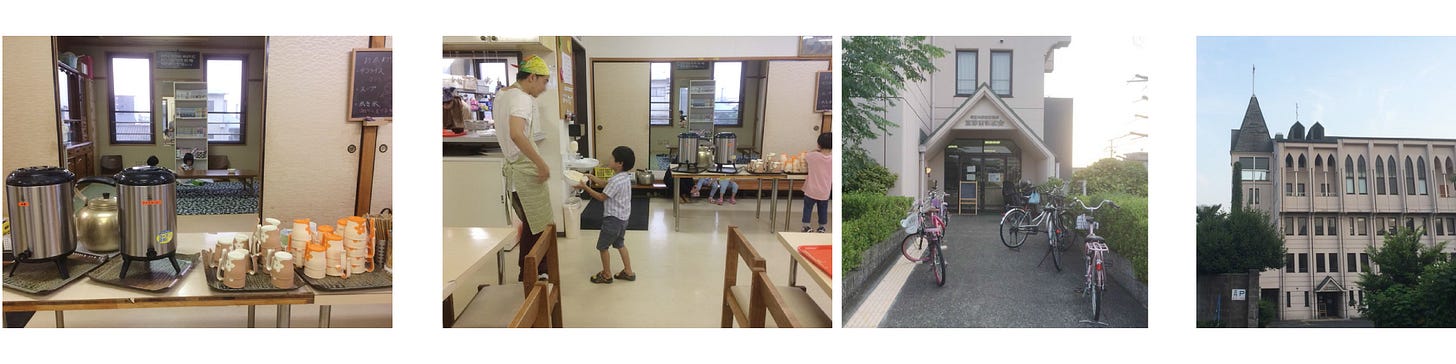

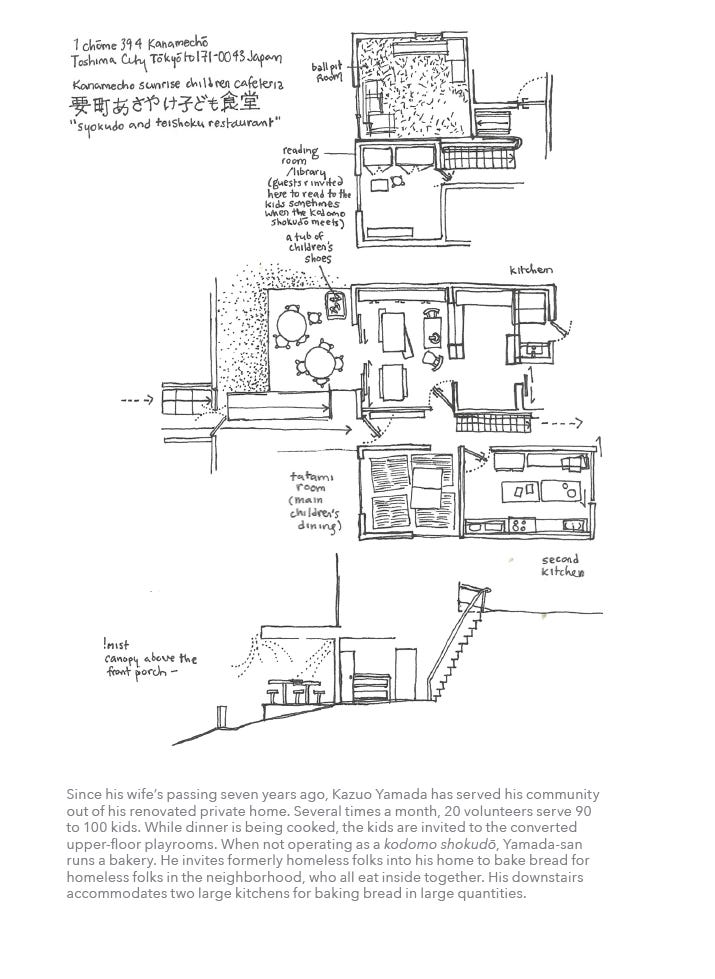

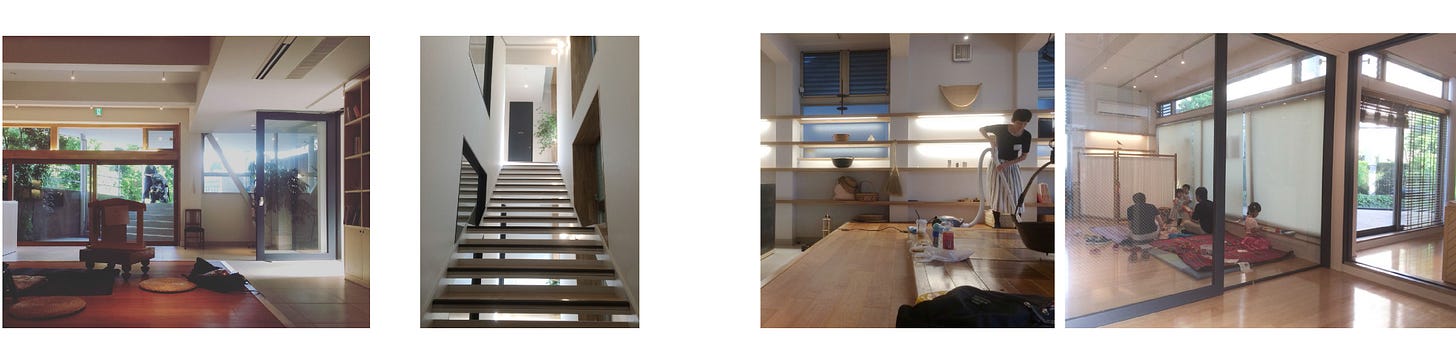

During the summer of 2019, I visited nine urban kodomo shokudō in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto. Their sites included a restaurant, a public school, a renovated house, a temple basement, a church, a nursing home, the small entry vestibule of a corporate office, and a private home. Coordinators of kodomo shokudō lack the means to construct new buildings and instead appropriate domestic interiors or temporarily occupy existing commercial sites. Their idiosyncratic use of space is prompted by the programmatic needs of participatory cooking and eating. These spatial strategies can inform the work of architectural designers seeking to better serve communities in need.

Visiting briefly, I couldn’t access the daily lived realities of the people I met. All I could access were the spaces they occupied and the food they shared with me. In many cases it was not appropriate to take photos, whereas making drawings was both a research tool and an invitation. Drawing became a catalyst for conversation and interaction, overcoming language barriers, giving time for people to share their stories, and sparking the interest of kids.

Daisuke Machida, Yuko Nagai, and Tohru Yoshida. “Factors Related to ‘Activity Independence’ of Staff of Kodomo Shokudō Eateries: A Cross-sectional study Focusing on ‘Activity Satisfaction’ and ‘Activity Burden’” (February 2019).

Aya Hirata Kimura. “Hungry in Japan: Food Insecurity and Ethical Citizenship,” The Journal of Asian Studies 77, no. 2 (May 16, 2008).

whoaaa so interesting to get a glimpse into these things via floor plan & their stories