Psychogeographic Belvedere

Humidity-Directed Drift

We’ve already passed the season. It’s right around the time the mustard has started to die out on the hillsides, staining them brown, tawny, and ochre, months since they’d been dotted with pink plastic flags for future plantings and spotted with the silhouettes of ravens. It’s just before the jacarandas bloom on either side of south broadway, framing out the underside of the 10 freeway facing north in lilac, periwinkle, and indigo, contrasting sharply with the vivid orange of a city bus. It’s when the color of the loquats has veered sharply towards red, past the softly yellowed hue of a tart fruit and deepening into a thickly sweet, vermilion mass.

The lonely ice cream is a late May phenomenon. It doesn’t happen every year, and it can only happen one time per year. It should be slightly muggy, the first night where dusk is accompanied by a blithe lack of concern for potential cold. You didn’t drive for it—you walked, or you biked. The introspective quiet of ambient city streets and strangers, the anonymity of proximity without interaction, is a big part of it. You cannot plan for it, it happens on a whim, it exactly hits a craving, it’s vaguely sad, and important that it be solitudinous–you’re on your way back from somewhere, alone, or you’ve made this into a paltry excuse for an errand as a reason to leave the house. It’s just a jaunt for a jawn.

I had one this year. I missed it last year. The year prior, on the first warm night with air swelled up like a pillow, I left my one-room apartment in West Philly. A crescent moon was hanging low, framed in cobalt skies sitting heavy on top of aegean grey-blue clouds lining the horizon, lit from below by the red and yellow signage for ‘Chris’s Pizza’ next to the vacant lot. I waited on a soft serve swirl handed across a countertop open to the street, by pierced teens with hair dyed various neon shades, and took the long way home.

In his 1928 work One-Way Street, Walter Benjamin marks a difference between the act of walking and vehicular modes of travel by drawing out a double analogy between walking and the “Chinese practice of copying books,” where the act of transcription “commands the soul of him who is occupied with it.”1 The passenger in an airplane —or reader— is more passively engaged, while the walker —or writer— “submits to command” that which they observe:

“Only he who walks the road on foot learns of the power it commands, and of how, from the very scenery that for the flier is only the unfurled plain, it calls forth distances, belvederes, clearings, prospects, at each of its turns”2

The cadence of walking reveals aspects of place that are otherwise indiscernible. The word belvedere, at its root Italian for “beautiful view,” by architectural definition refers to an elevated structure that provides lighting and ventilation to “command a fine view.”3 Described as “roofed but open on one or more sides, a belvedere may be located in the upper part of a building or may stand as a separate structure. It often assumes the form of a loggia, or open gallery.” Directing the gaze of an inhabitant, a belvedere is a framing device, a structural component that designates a way of looking.

Sometimes I experience a street corner that is, plausibly, a different street corner. This differs slightly from « déjà vu » —literally, “already seen”— the unsettling strangeness produced by “the illusion of remembering scenes and events when experienced for the first time.”4 « Déjà vu » often involves elements I can’t articulate, or place in a logical timeframe or physical context, whereas my ghosts of the urban environment retain visual indicators and physical cues that I can pinpoint with more exacting detail.

In a recent memory, I retain the sensation of being in a mid-size car, pulling up to a slightly rounded and slightly raised four-way intersection. We were driving from the north, facing south. The sun in the rearview mirror doesn’t give me a hint if it was a subtle morning or a muted afternoon, but based on the slight warmth on the right side of my face from the passenger seat side, that would make it a falling sun, the latter half of the day, when this situation evokes the ghost of the earlier memory.

In the misplaced memory, the overlapping memory, the prior, earlier memory, I’d just stopped in at an REI bikeshop basement for tubes or possibly tires—Armadillo or similar, for longevity against glass-shard-scattered streets. I’m coming from the south and headed north, slightly uphill. Though the physical details ease my articulation of sameness and difference, it isn’t really that the structural form or literal attributes of the two street corners remind me of each other. The experience of the second is jarring because the misplaced memory that I’d overlaid on top of it, in real time, situated me.

The mental gymnastics of superimposing a prior situation on top of a current one is partly the product of a homogenizing, globalizing world, continually paved over with pervasive sameness. The flattening quality of observing that something ‘looks familiar’ isn’t what’s compelling to me here, though. That the details of this urban structure, the particular slope of this hill, the arc of this clearing in the forest, the sweep of this part of the river, evokes a visceral familiarity and provides me with a sense of place, belies a different type of encounter between the two situations. The double memories operate as twin apertures, as framing devices for each other.

The eve of the summer solstice, a month after my seasonal ice cream melancholy, I bike the concrete channel of the LA river, bright with birdsong, the shallow water catching a new angle on the sun, throwing shimmering golden refraction up onto every surface. The air is weighty and wet, camping out in my nasal cavity, in the precise balance of my eardrums, in the way my breath catches, pillowy, in my throat. The crepuscular hour in LA isn’t threatening rain, but the heavy air still leaves me deeply saturated in a ghostly sense of place heightened by humidity.

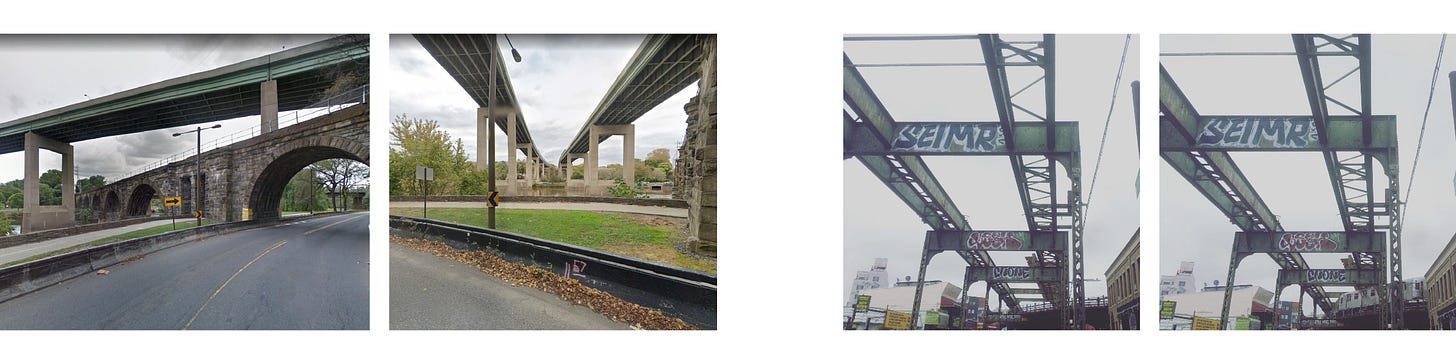

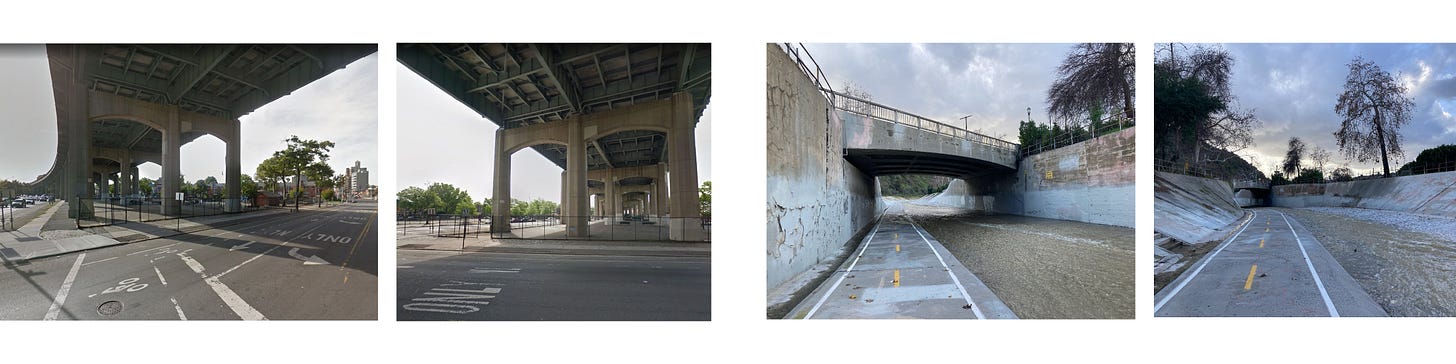

Summer nights and early mornings, I’d bike to the Dirtbaby Farm plots in Roxborough and back downhill to the eastern bank of the Schuylkill; tracing through the immense greenery to the railroad tracks at Shawmont station; across the creek bridge at the base of Wissahickon; uphill along Kelly Drive, parallel concrete pillars holding up the seafoam green underside of City Ave, framing out green leaves, a freeway overpass portrait of river, forest, and the various paraphernalia of human settlement and industry; across the bridge at Strawberry Mansion, or, if I haven’t yet passed the bridge, the pleasingly trapezoidal building at the southernmost end of the Rowing Finish Line Grandstand. The throughline, that hot heavy air in LA, generates now “a tangible reliving,” the “rebirth of a sensation…still intact.”5

“Is there anything more vertiginous than gustative reminiscence? For it upends completely the conventional workings of memory … something appears without being summoned, something that does not serve as a witness to anything, that does not help me to follow the thread of my memory.”6

Like the Proustian unconscious memory stirred by a madeleine dipped in tea, the nameless narrator of Garréta’s 1986 novel Sphinx is profoundly disoriented by a memory of taste.7 The effusive and flowery quality of Ramadan’s English translation here captures something of the insurgent, corporeal quality of memory. If the summer season is an apt time for the evocation of various nostalgias, and if gustatory [adj. relating to or associated with eating or sense of taste]8 and aromatic [adj. of, relating to, or having a distinctive, pervasive, and usually pleasant or savory smell]9 constitute especially effective conveyances of memory, I’d argue that the level of moisture in the air similarly evokes the “intense, fugitive form” the “carnal presence” of memory.10

The smell of heat on the air is the connective tissue of weather experiences. For me, it’s years of watching summer storms split the sky in violently violet-white cracks of lightning from New York rooftops, or getting caught in a rainstorm walking in the New Jersey woods, then watching the rain slide sideways across the yard from the back porch, still damp. On the east river with MH, I mention how T, A, and I used to go walking down on the river in New Jersey throughout high pandemic lockdown, exclaiming blissfully, “it smells like Japan!” “Oh, for me, it’s Chile–that hot pavement smell,” MH says, hot air sitting heavy in our noses on the Brooklyn waterfront, the rose-colored tint of places we’ve visited but not lived predictably framed at the center of our humidity-infused imaginations.

Several weeks ago, a friend mentions the term psychogeography to me when I describe my ghosts of the urban environment. At first I’m certain it was E, on one of our rambling four-hour phonecalls, subsequently, that it must’ve been SZ or JH. When it isn’t, I suspect ES, though it’s unlikely since I’d discussed the term with BX on our flight out, prior to meeting ES at the divey Irish lesbian bar by the park. It’s possible that it had been JD the week before. When I mention the term to MH, she agrees that the definition seems intuitive. Mental maps, D and R say later, from their lower-level brownstone apartment, sheltering from a downpour when a thunderstorm rolls over Brooklyn.

I imagine that psychogeography, unlike aspirationally ‘objective’ mapmaking focused on concretized structures and literal landforms, is more openly premised on subjectivity. I envision a looser mapping that includes seemingly random landmarks, marking various detritus that is of particular note only to a specific viewer, notations that stand out not so much as destinations, per se, but as bits and bobs along the way. Picturing these disparate nodes, I see them linked by psychological bridges, the spans between my doubled memories. The ghosts, the twin apertures, collapse time and space into a single Frankensteined memory.

Back on the subway after the storm has let up, I’m thinking about the long-anticipated regional connector back in Los Angeles. Those of us who regularly take the blue line through Compton and South LA know the recognizable odor of the metro cars, with their unwashed hard plastic seats and run-down interiors, frequented by unhoused neighbors without another place to seek shelter. This contrasts sharply with the newly-upholstered seats of the cleaned-up cars on the Pasadena end of the gold line, frequented by tech workers wearing their usual unsettling combination of banal middle-aged-office-worker cosplay coupled with the backpacks and motorized scooters that belie their callow, grade-school naiveté. Now, the two occupy a single line.

The collapsed space between historically redlined and under-resourced neighborhoods, oftentimes sites of pollution where the worst of the county’s housing and mental health crisis has been permitted to proliferate, abated mostly by the care of local residents and neighborhood groups in the absence of city funding, and the affluent, suburbanized areas where civic dollars have been hoarded to construct exclusionary public space in whiter, wealthier neighborhoods, proposes two things at once. Access to public transit disrupts existing neighborhoods, spurring gentrification, and can provide a democratic flattening, a shared place where different walks of life commingle.

By Marxist theorist Guy Debord’s 1955 definition, psychogeography, the intersection of psychology and geography, describes the effects of the urban environment, “consciously organized or not,” on the emotions and behaviors of individuals.11 Per Debord, there is a “pleasing vagueness” to this definition, which regards playful and inventive wandering in the urban environment as a means of reclamation, where encounters are not predetermined or fixed, and have no clear or singular objective. To regard our surroundings in this way, as individual nodes within a vast network of possible connected dots and constellations, leaves space for the known and familiar to be made new. It’s simply a matter of attention.12

“Certain forms of [attention] are contagious. When you spend enough time with someone who pays close attention to something (if you were hanging out with me, it would be birds), you inevitably start to pay attention to some of the same things… Patterns of attention–what we choose to notice and what we do not–are how we render reality to ourselves, and thus have a direct bearing on what we feel is possible at any given time”13

(If you were hanging out with me, it would be the undersides of highways, bridges, elevated rail lines, and freeway overpasses.) Biking underneath the elevated rail in the Bronx or tracing it East out towards Flushing, walking under freeway overpasses in West Oakland and Temescal, downtown towards the lake or north towards Berkeley along Telegraph, under the highways that pass over the concrete channel of the LA river in Frogtown or parallel to the 5 crawling north, New Jersey turnpikes that I crossed weekly by bike for the nearest grocery store, the protected bike lane in the dark tunnel under the Vine Expressway to Fishtown from South Philly, these belvederes are linchpins in my psychogeographic mapping, apertures back to myself.

While I’m fraying the loose ends on this newsletter, I’m on the Kern River, camp cup of Folgers in one hand, hot, black, and bitter, cross-legged on a rock and typing with my thumbs. It’s overflowed its banks this year, submerging half the campsite. The sound of rushing water rages against the sides of our tents, a glorious and triumphant white noise that soars above the rustling of trees and clambering of a beaver who’s made a home in the fallen tree partway into the river, building out a dam that’s formed a protected pool where we swim and lounge all day. ‘We owe her our life!’ jokes S, partly serious, our bodies submerged in the glacial melt to escape over one hundred degree heat. Dunking my entire body under, I think of Marie Howe’s November 1983 “What Belongs to Us,”

“Not the memorized phone numbers. / The carefully rehearsed shortcuts home. / Not the summer shimmering like pavement … / Not even the way we said things, leaning against the kitchen counter … / Not even the blisters. Look.”14

Around the fire later, S and O come back into camp to surprise CH and I, candles lit in deference to the planetary bodies that are in motion around our bodies. It’s a chiffon cake S has picked up near the coast, neon green, yellow, and pink stripes of lime, passionfruit, and guava, frosted fruity slices that we eat with our hands, from the Hawaiian bakery nearer to my hometown than to my east LA apartment. The gel-icing put me back, all eight of us cousins still small, smoothing the frosting off with our fingers and licking them clean. I haven’t eaten this cake since I was nine or ten. The sponge slice, gripped in my campsite-encrusted fingernails, puts me back to the patio of AM’s place in Philly, eating hefty slices of cake with our hands for EV’s birthday, the pieces thickly satisfying in our palms. The tastes and tactility open twinning apertures, mirrors between multiple selves, spanning years, neither belonging to me, both belonging only to each other.

Benjamin, Walter, and Edmund Jephcott. One-Way Street. Edited by Michael W. Jennings. Harvard University Press, 2016. 1928. Print.

Benjamin, 1928.

Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/belvedere

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/déjà vu

Garréta, Anne. Sphinx. Translated by Emma Ramadan. Dallas, Texas: Deep Vellum Publishing, 2015. 19 February 1986. Print.

Garréta, 1986.

Proust, Marcel and John Sturrock. À la recherche du temps perdu. Swann’s Way Vol 1. New York: Modern Library, 2003. 14 November 1913. Print.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gustatory

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aroma

Garréta, 1986.

Debord, Guy. “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography.” 1955.

Ridgway, Maisie. “An Introduction to Psychogeography.” The Double Negative, 12 October 2014. http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/2014/12/an-introduction-to-psychogeography/

Odell, Jenny. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Melville House Publishing, 2019. Print.

Howe, Marie. “What Belongs to Us.” November 1983. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?contentId=35642

I enjoyed this lyrical and wandering ramble thru the underpasses of your mind.