Calibrated Imprecision

Sketches of Unfixed Form

For two full days after experiencing Julius Eastman’s work performed live, juxtaposed with a series of Arthur Russell arrangements, I remain in a daze. At one point, off the cuff, I try to describe what I’ve heard. I call it either “insistent urgency” or “unrelenting insurgency.” I’ve been trying to recall the exact phrase I’d used for a week now but can’t pinpoint it. In a way, the former misremembered phrase describes my visceral experience of the first Eastman piece Evil N— while the latter describes the impact of the second Gay Guerrilla.

Imprecise recollection aside, the textural quality of either phrase points toward what I’d been trying to describe in both Eastman scores: that the repetitive motif, with its rhythmic circularity, evokes the banality of living, in turns yearning, striving, and rageful. Performed live, the largely-improvised scores illustrate plainly that every seeming-repetition is, in fact, idiosyncratic and unique. In this way, the work feels somehow like a disavowal of linear time and a depiction of it. The relentless repetition and circularity is assembled from a series of superficially redundant phrases, destined or doomed to never quite repeat themselves, eternally new.

The forward movement of these Eastman phrases does remind me of the only other Russell piece I’ve seen performed live, 24→24 music by Russell’s disco project Dinosaur L, for which Eastman played keys. That same pulsating quality is only one aspect that stands out to me from the arrangements, whose haunting melodies performed by an assortment of soloists each stand alone stridently, solitudinous, and knit easily back into the fabric of the collective, folded almost seamlessly into a single expression. The Russell melodies reach fingers back into my memory—existing, imagined, fragmented, collective—striking a nostalgic chord, or fabricating one, using a wide range of sounds: discordant and weighty, sweetly melodic with folksy familiarity, heartbreakingly plaintive in seesawing harmonics.

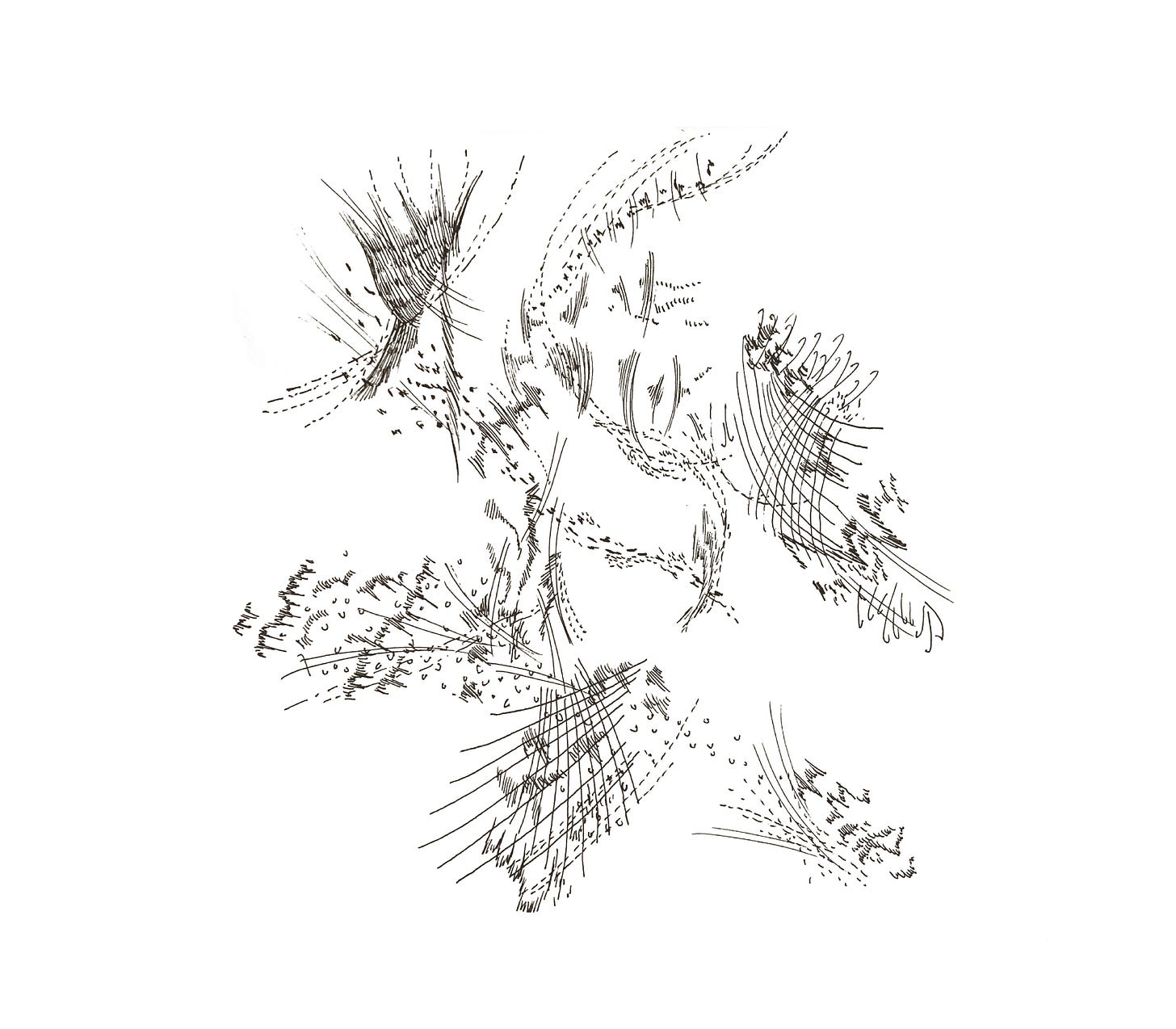

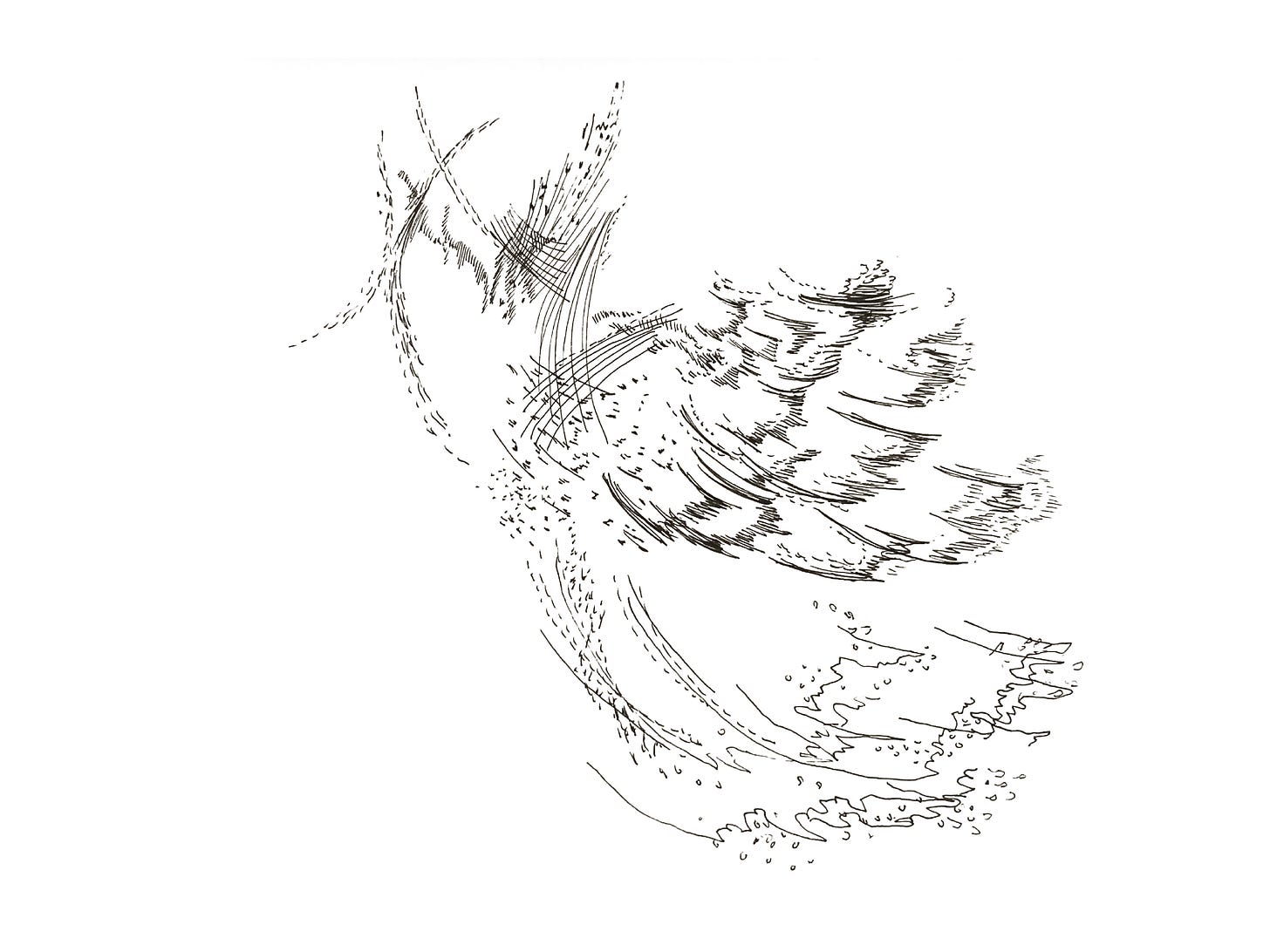

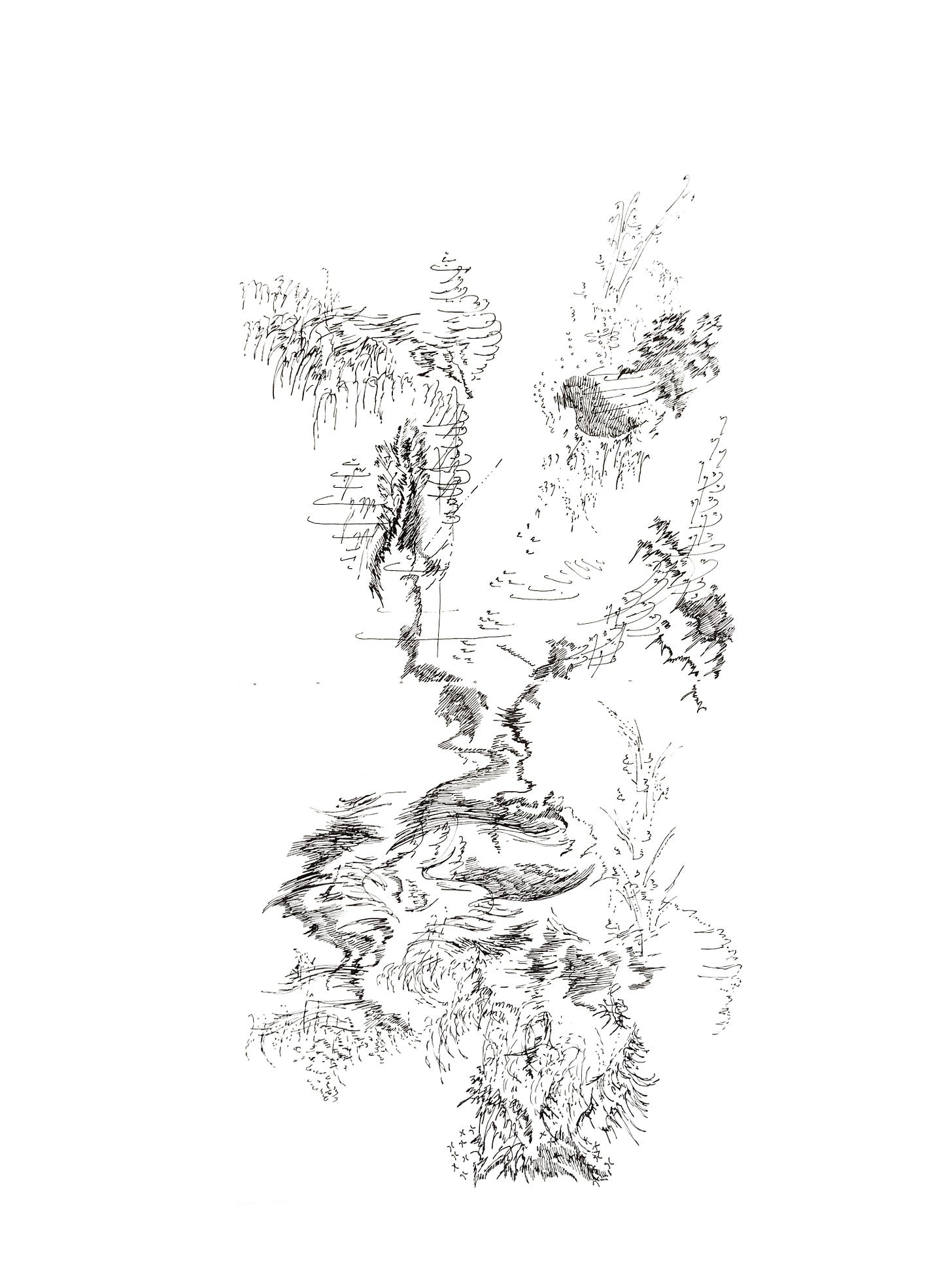

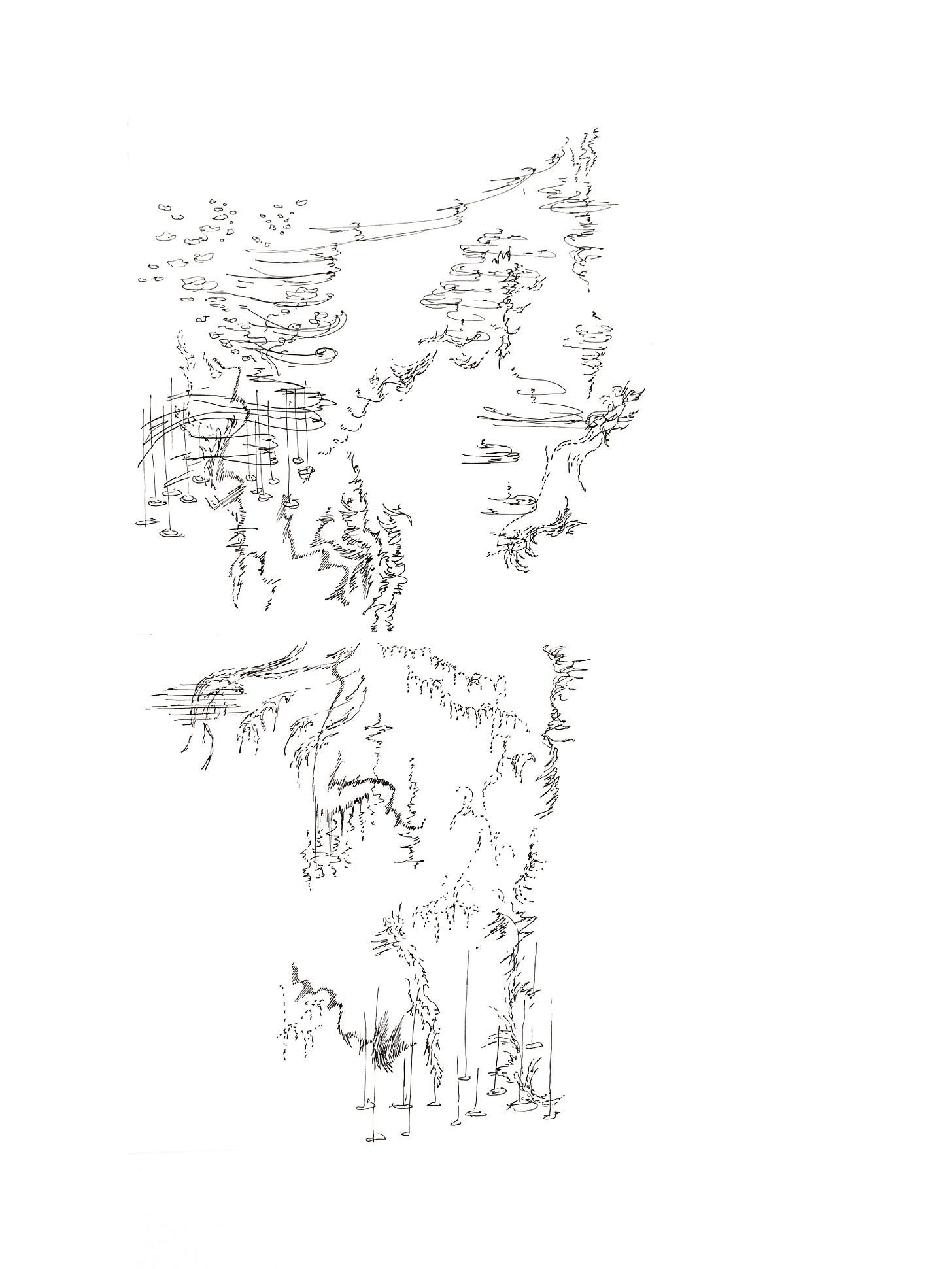

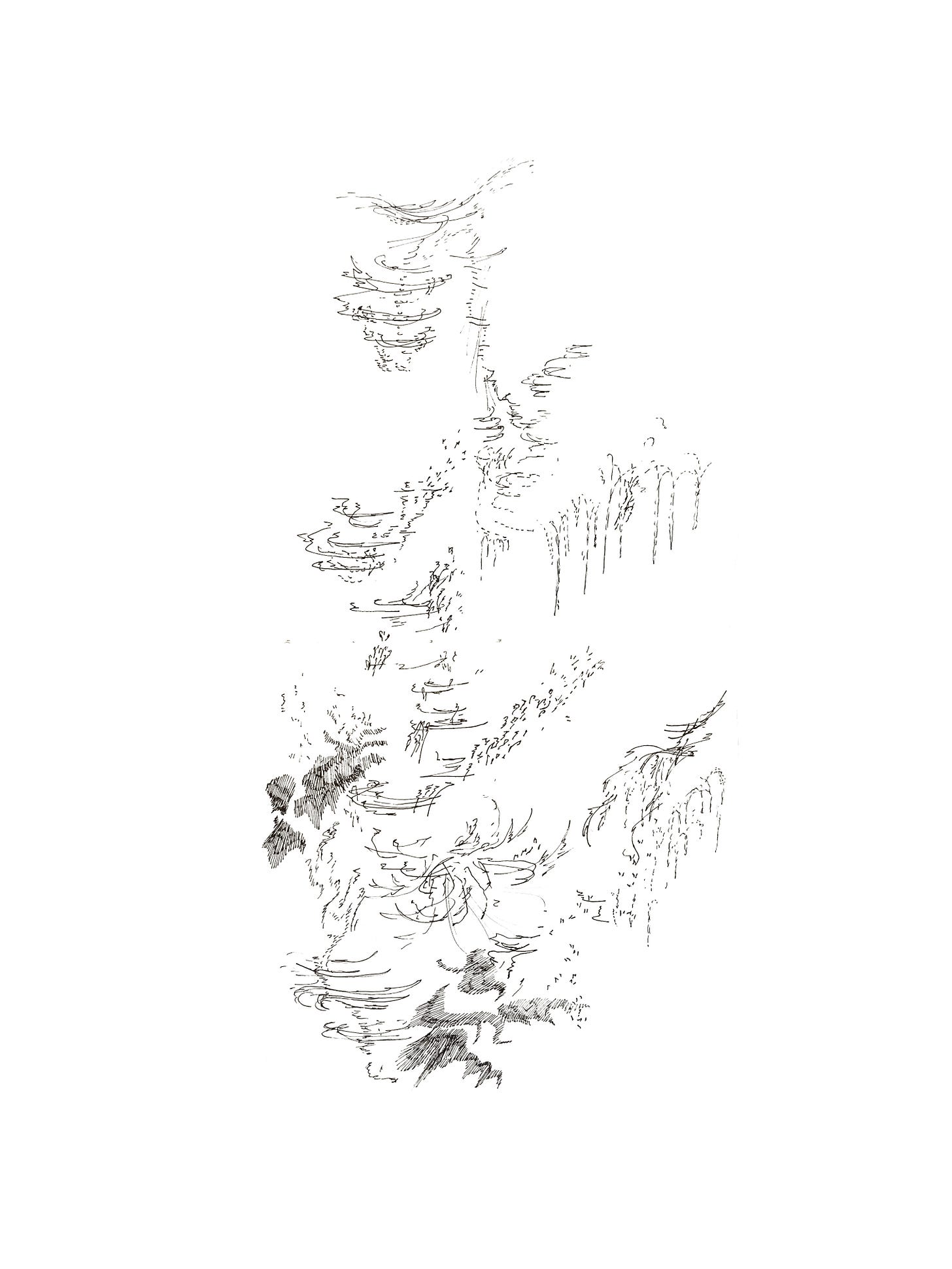

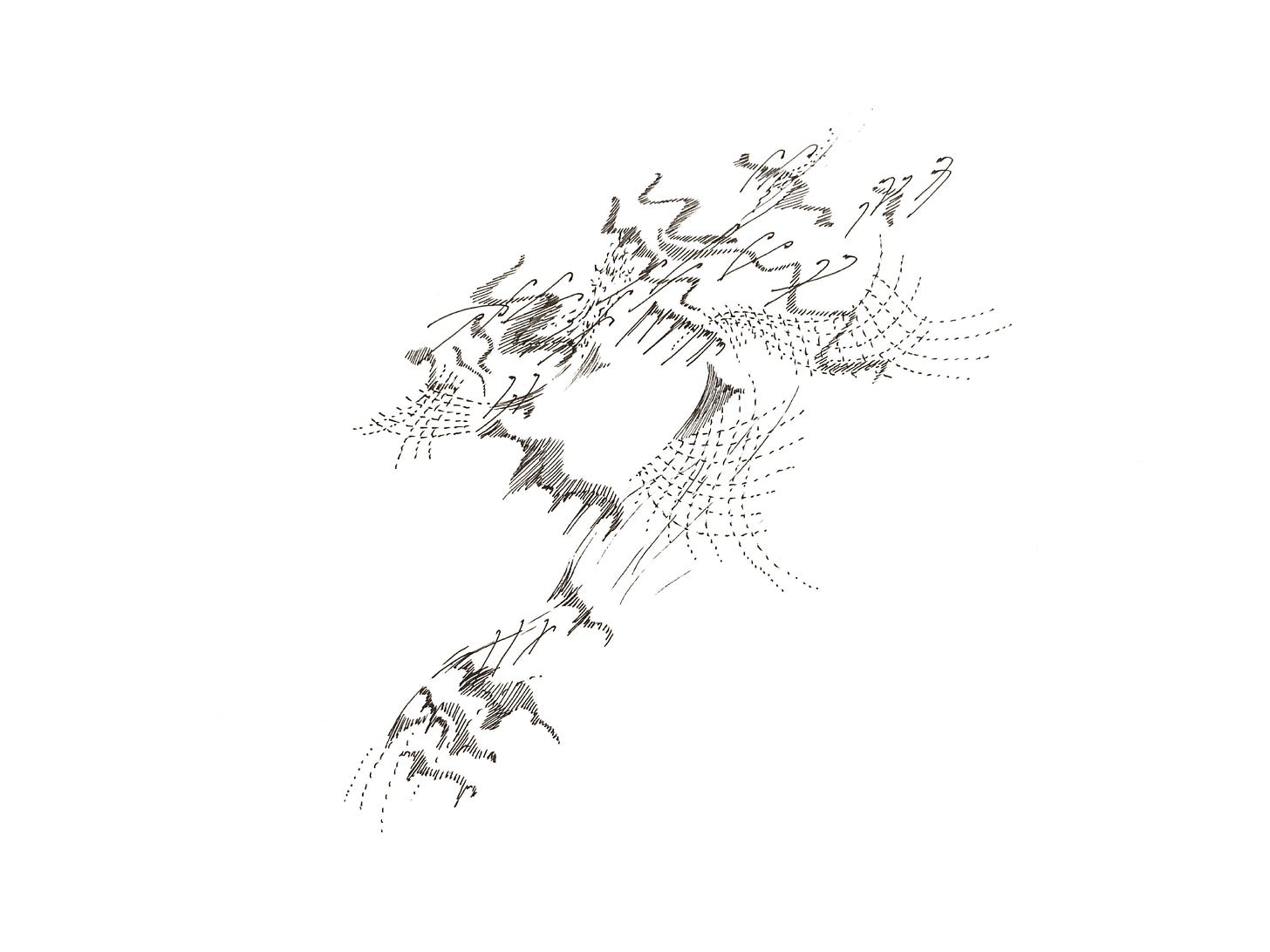

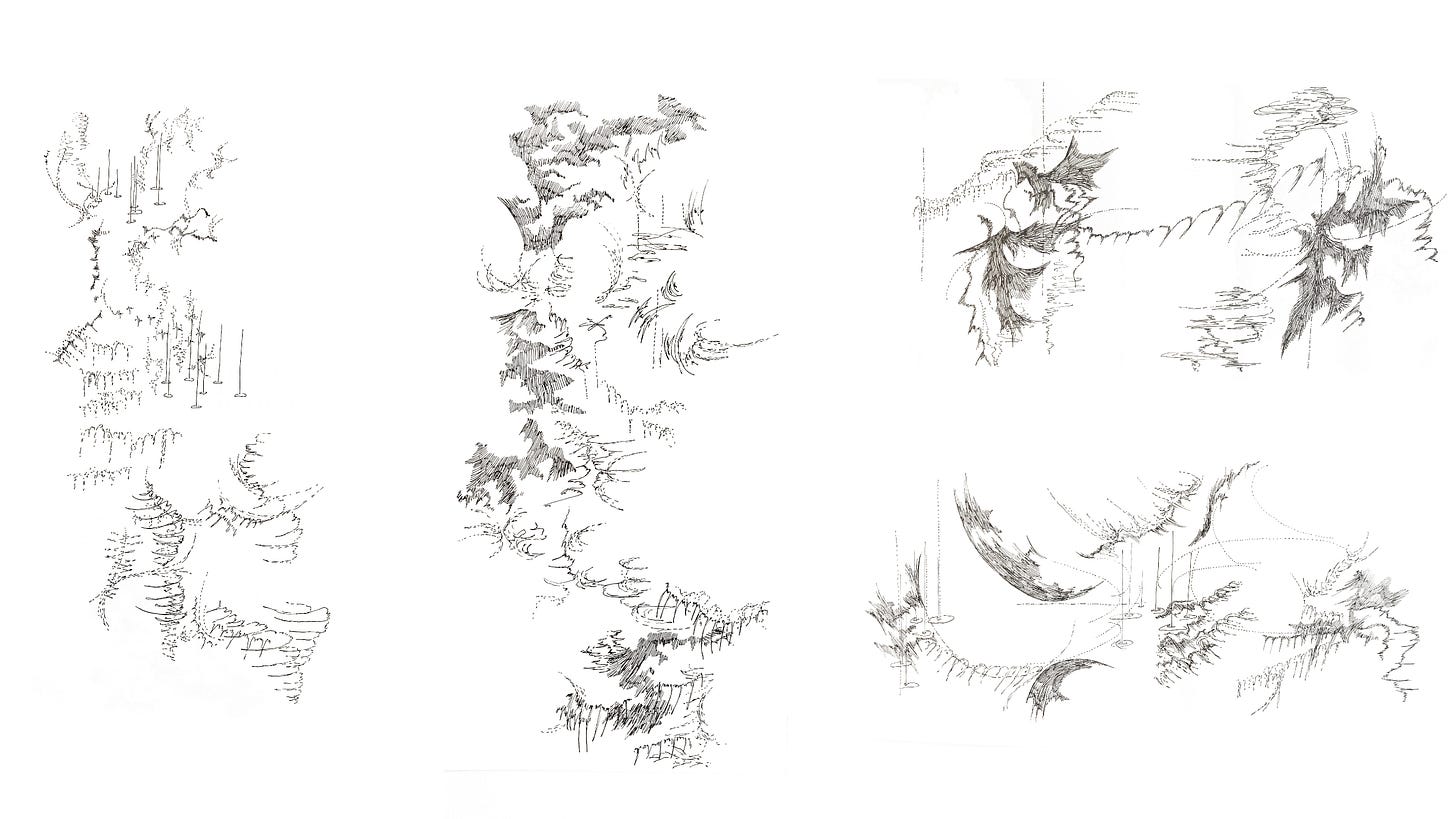

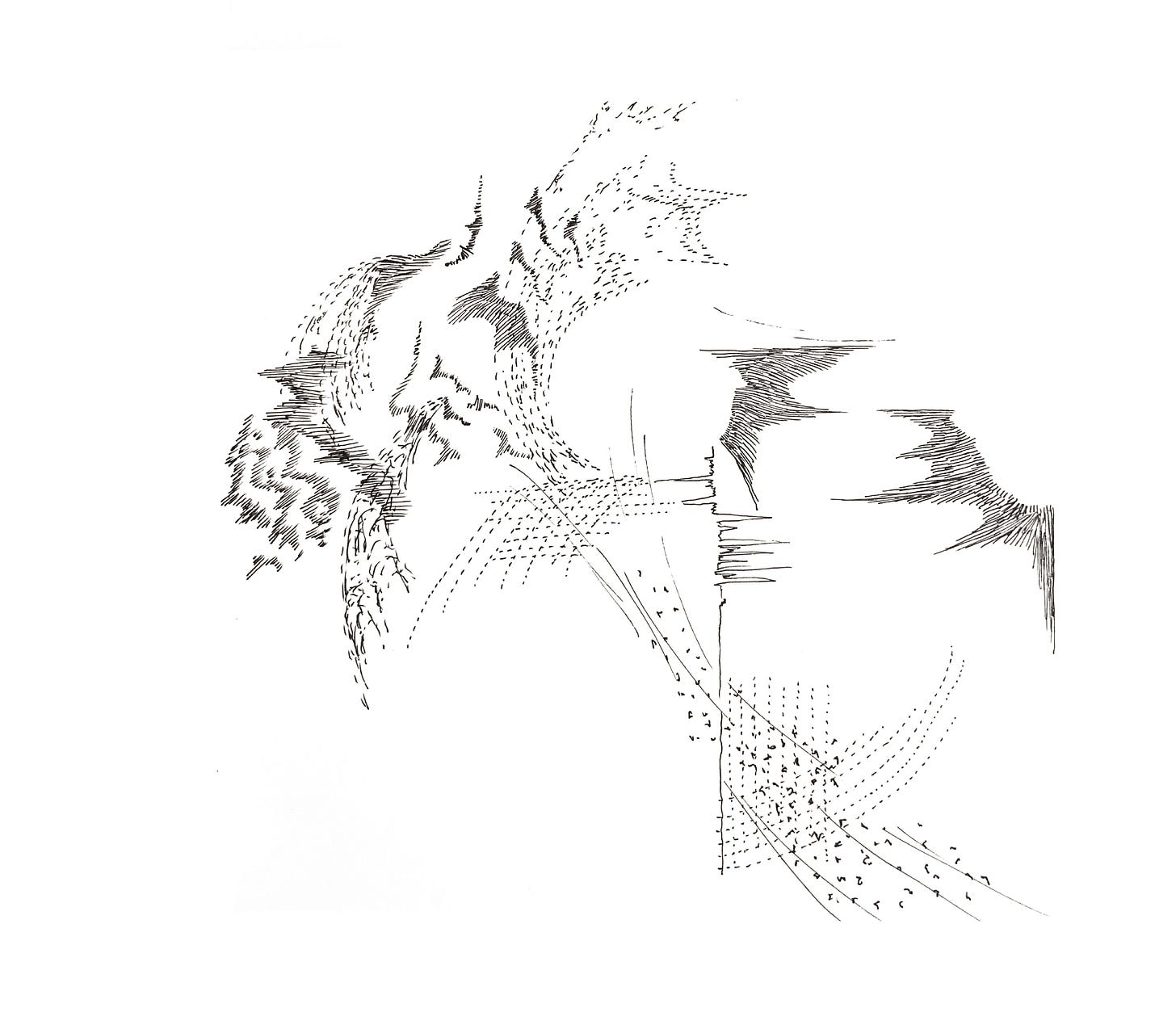

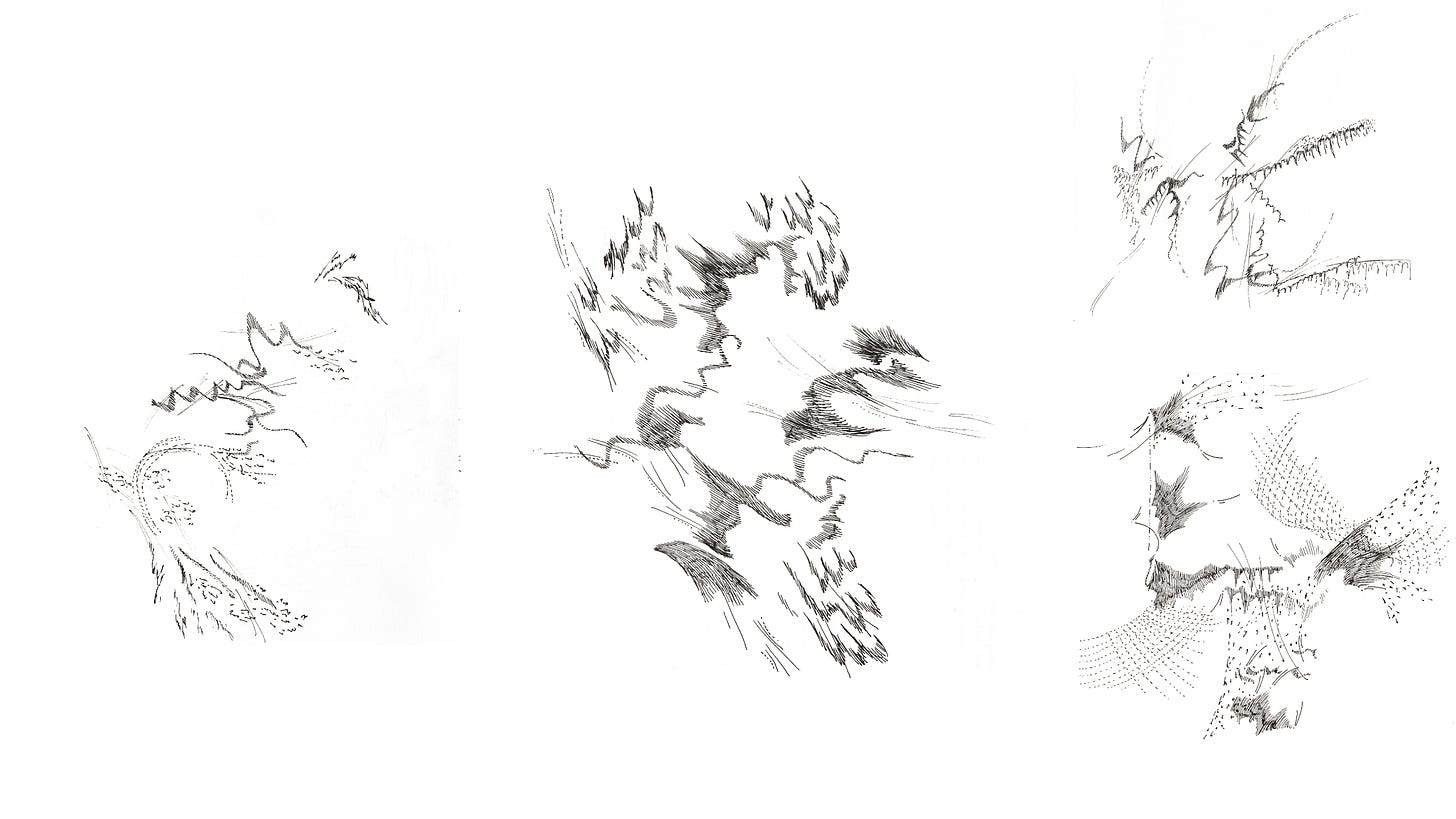

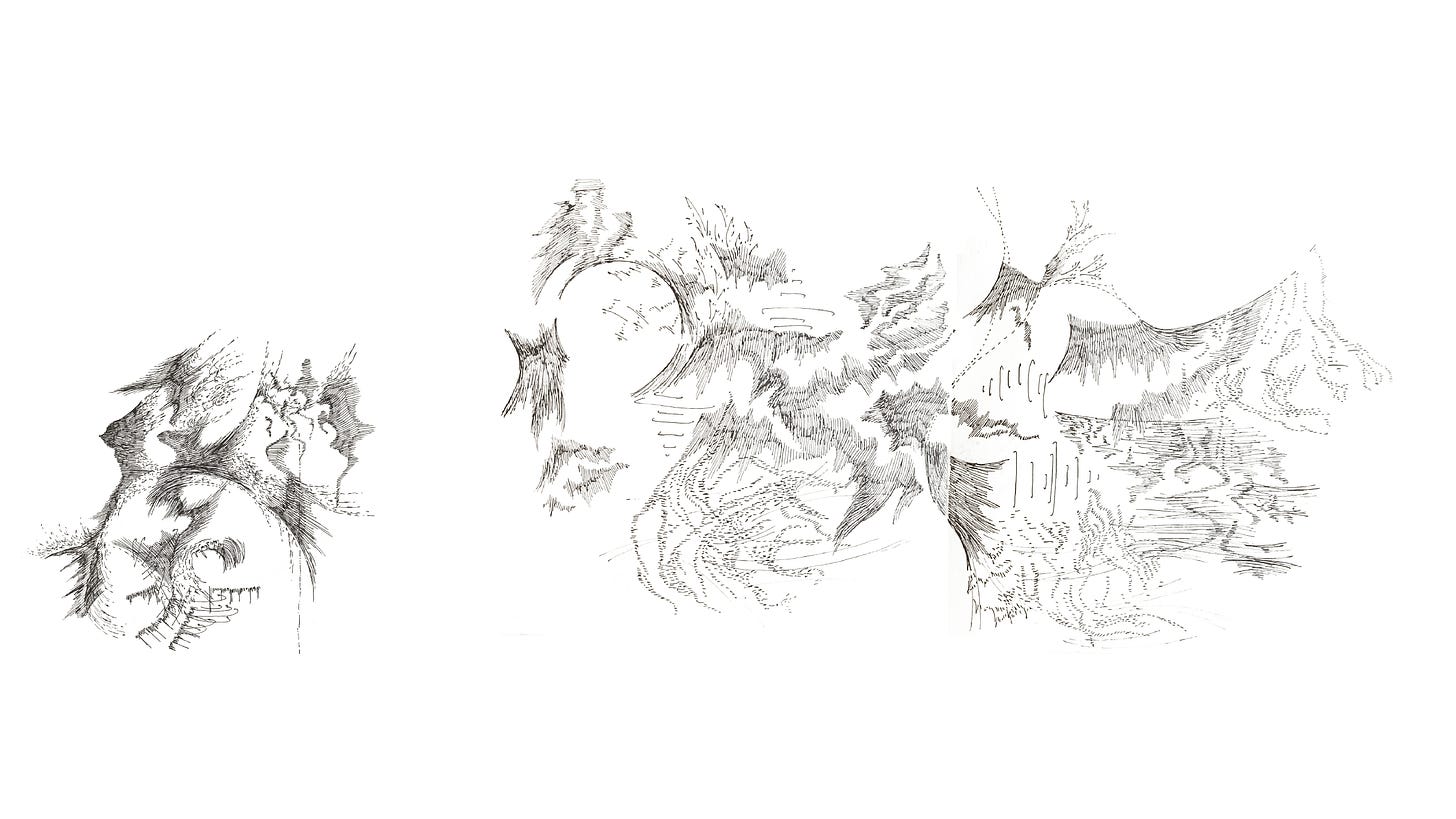

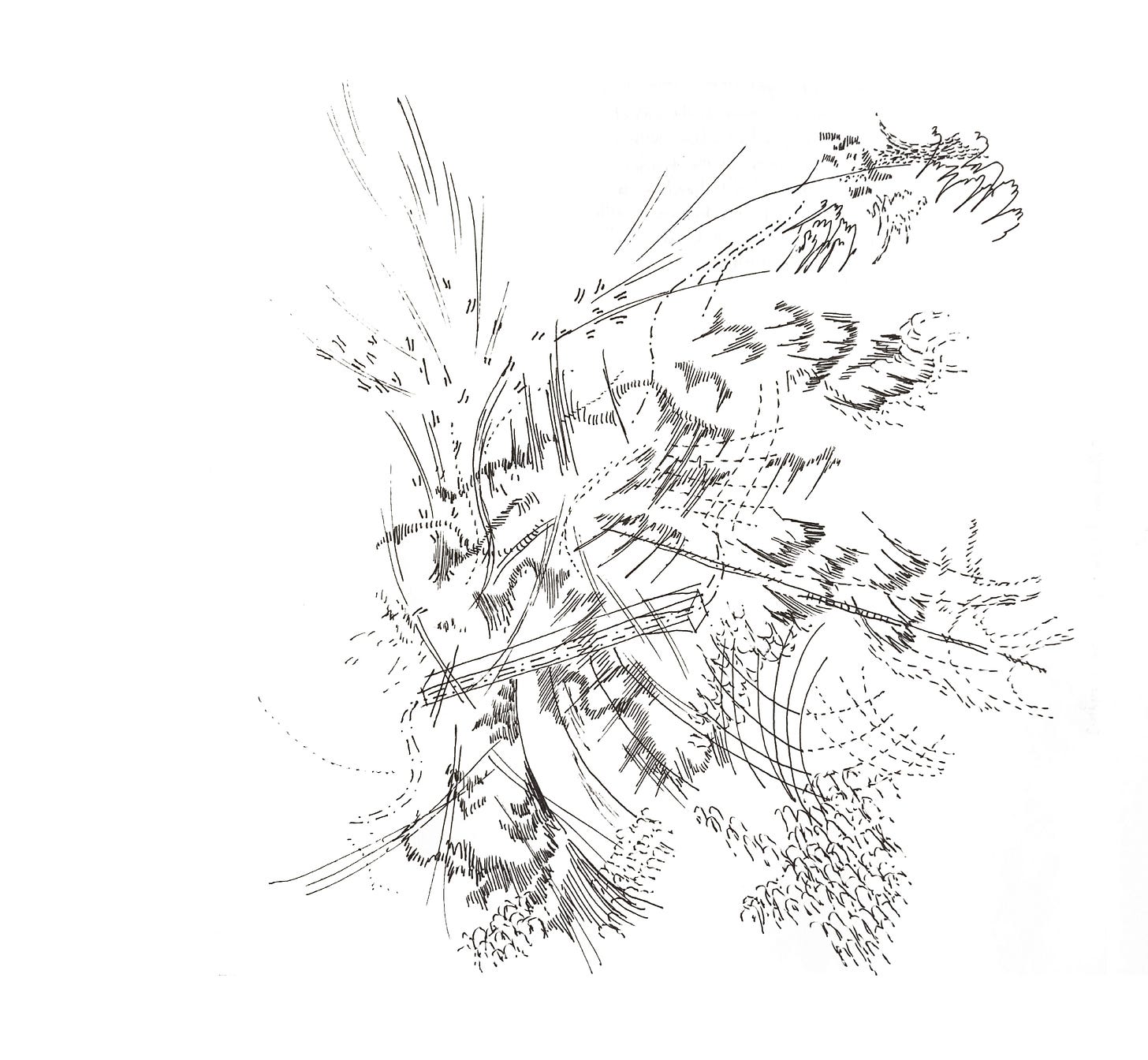

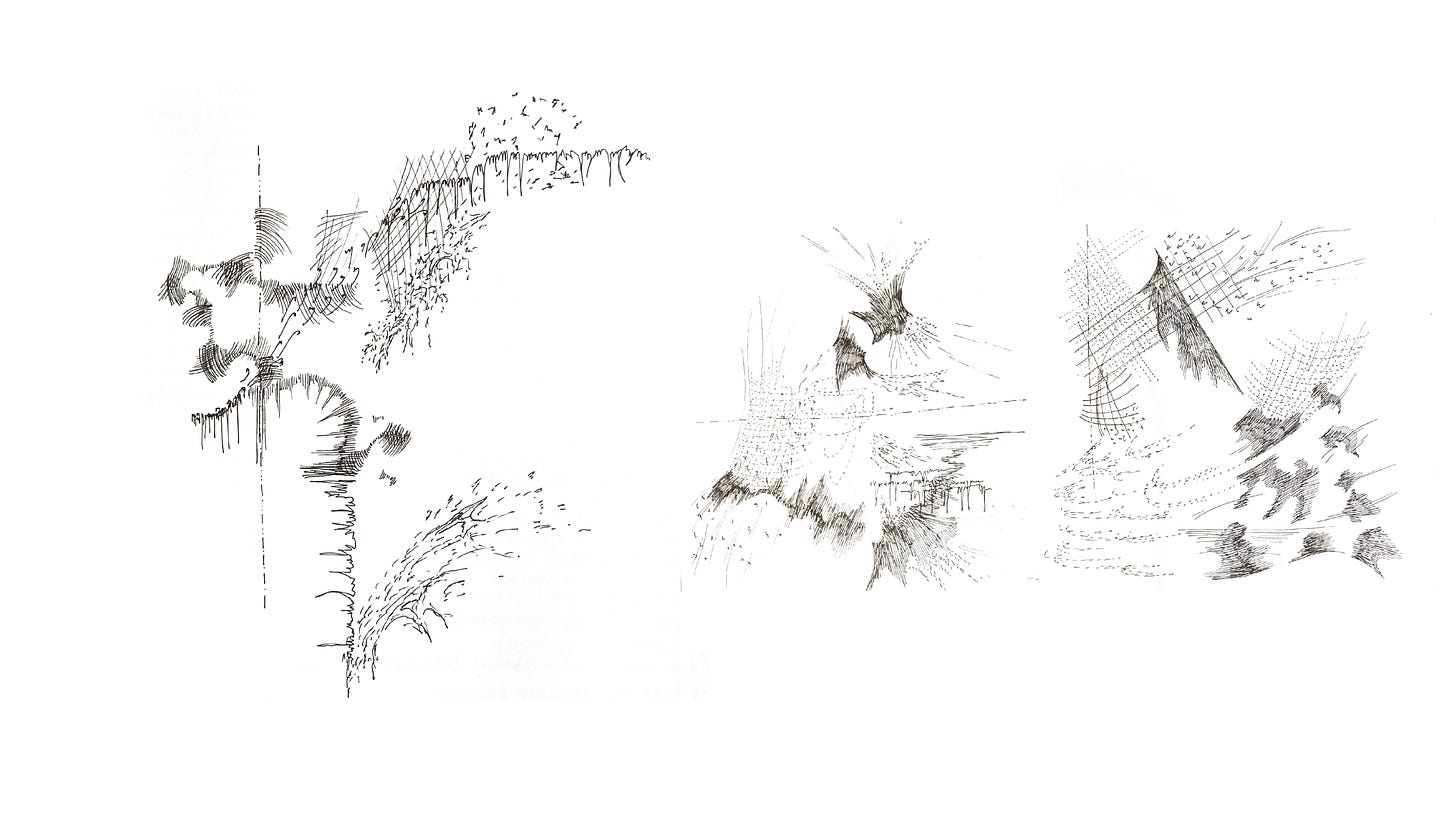

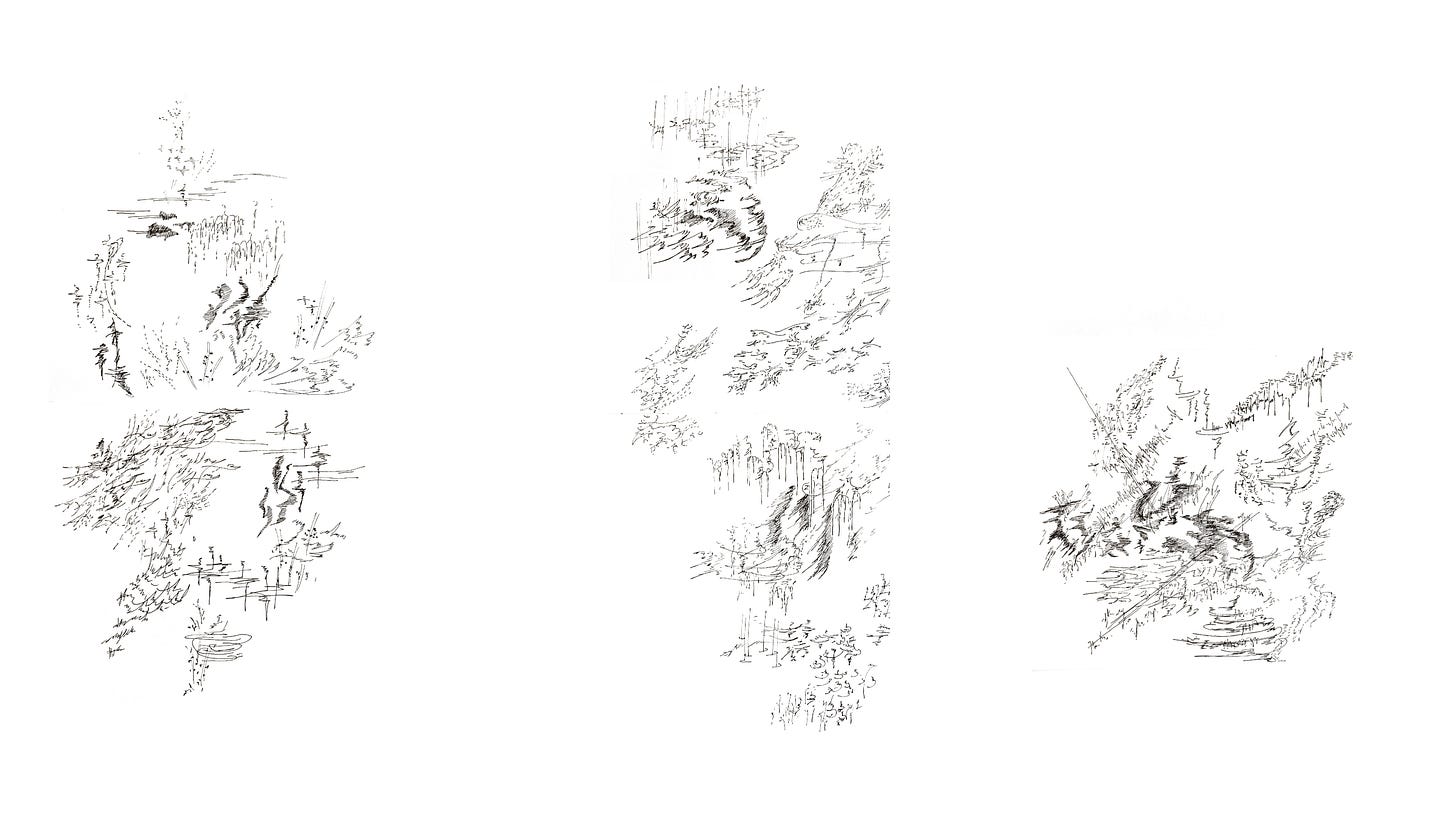

Sitting behind the stage, I draw sonic sketches for the duration of the performance, depicting each Eastman score and every Russell arrangement. Recently, I’ve been drawing sound and dance choreographies, recalling a teenage fixation with synesthesia wherein I’d wonder abstractly if I could train crossed wires in my own perception: see sound, hear color, taste words. Drawing at the show, at the dance performance, during the conversation, at the party, keeps my attention trained on whatever it is I’m trying to represent or document. This past month, I draw several improvised sets performed by friends, including a rendition of Pauline Oliveros’s 1979 El Relicario De Los Animales staged within walking distance from where I live.

The first performance that night, too, is ambulatory: Oliveros’s 1986 Thirteen Changes. Listeners occupy the in-between, the interstice, the margins, moving between groupings of performers staged across the grounds. The expressions of each sometimes interact, intentionally or incidentally, contingent on proximity and timing. Over the course of her life and work, Oliveros developed a practice that she called deep listening, initially named somewhat jokingly after a recording she made in a cistern 4.3 meters underground,1 and defined as “honing attention, and empowering people to use the attention to grow, and to explore and learn with sound,”2 articulating a distinction between involuntary hearing and listening as active participation.3 Her open-ended and largely-improvised scores provoke a practiced interdependence between performers, who are rooted in various contextual contingencies, directed by this choreography for spontaneous movement.

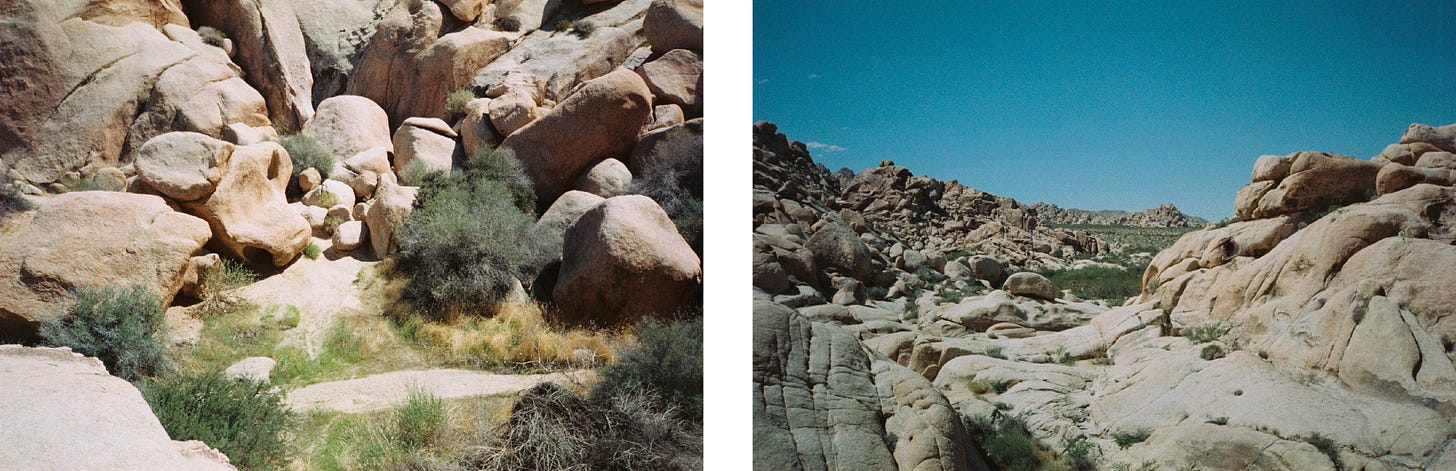

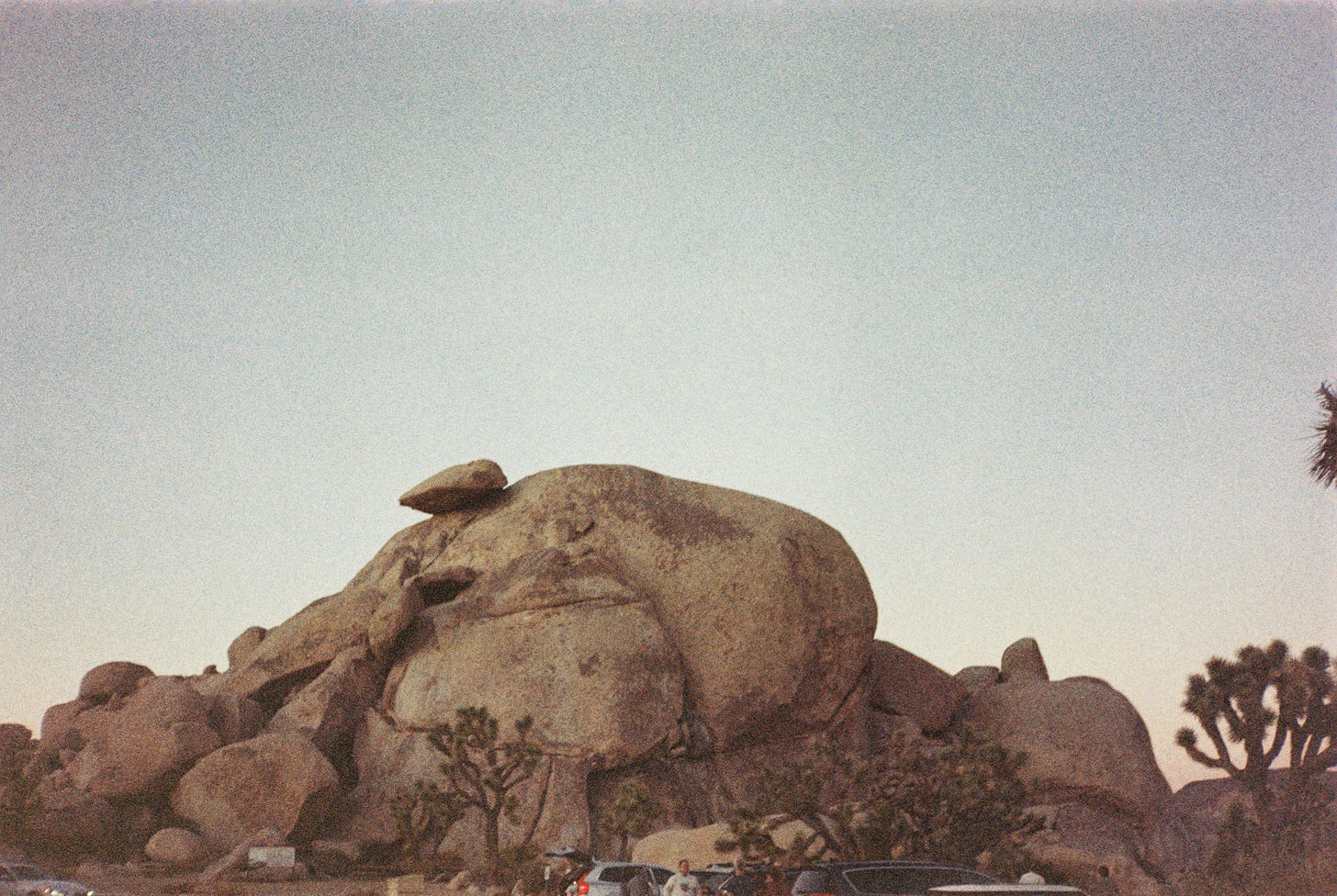

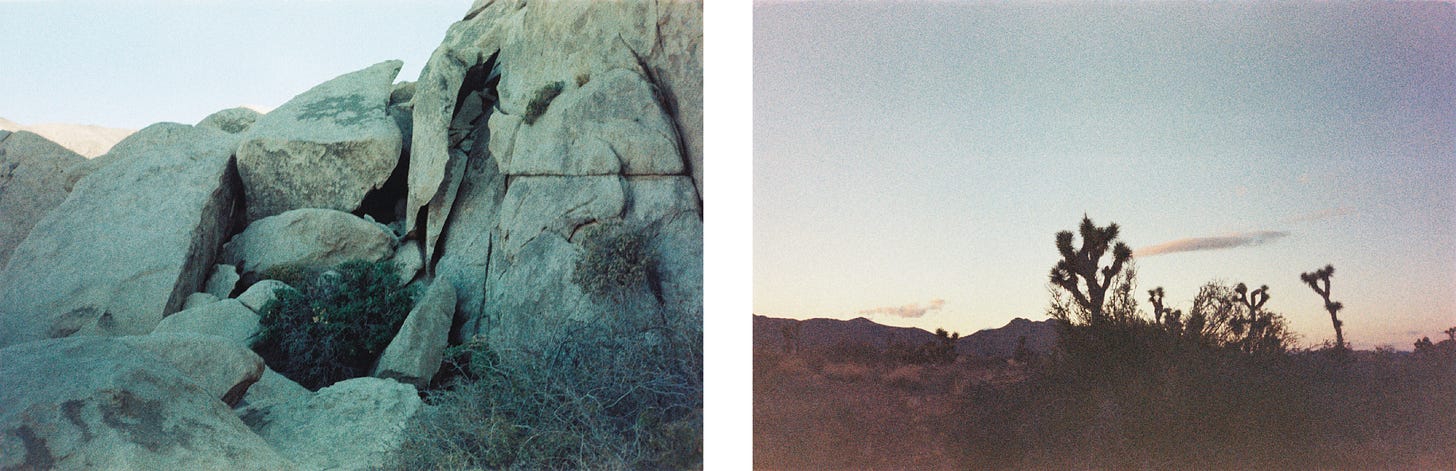

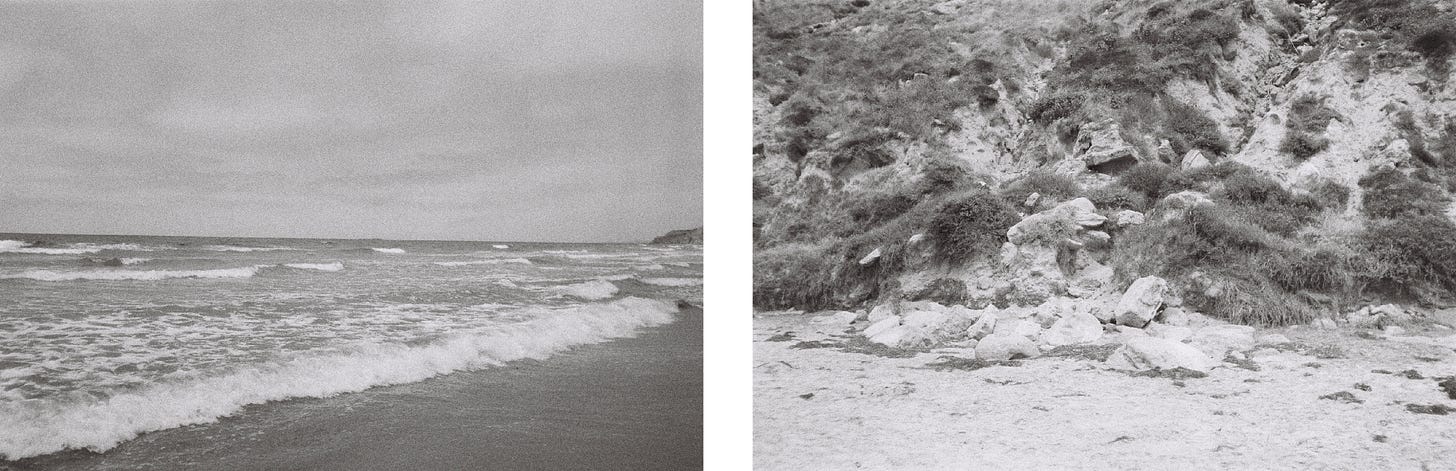

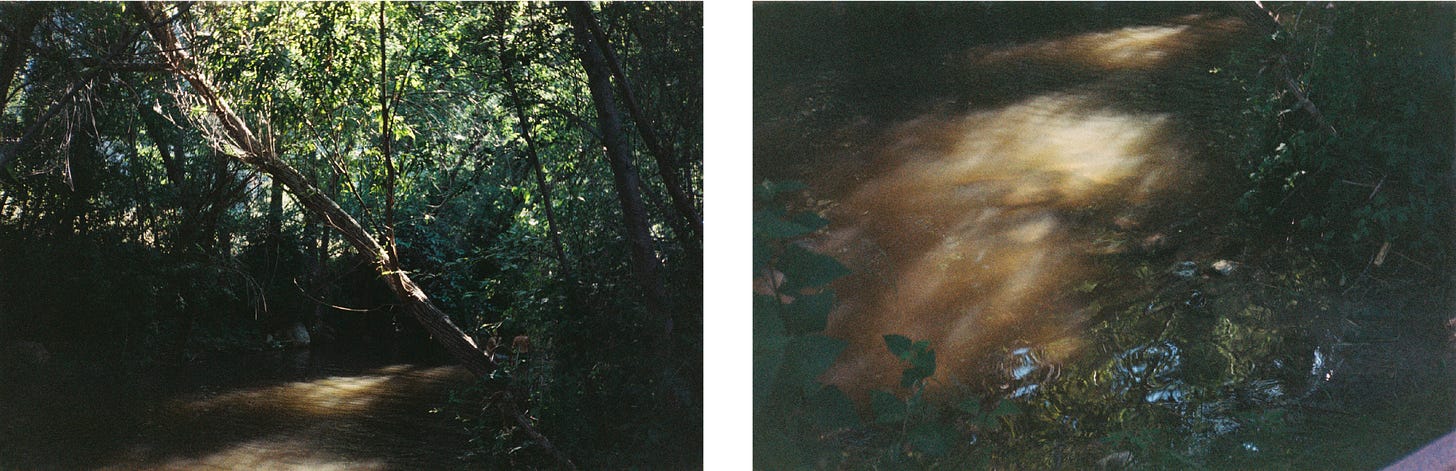

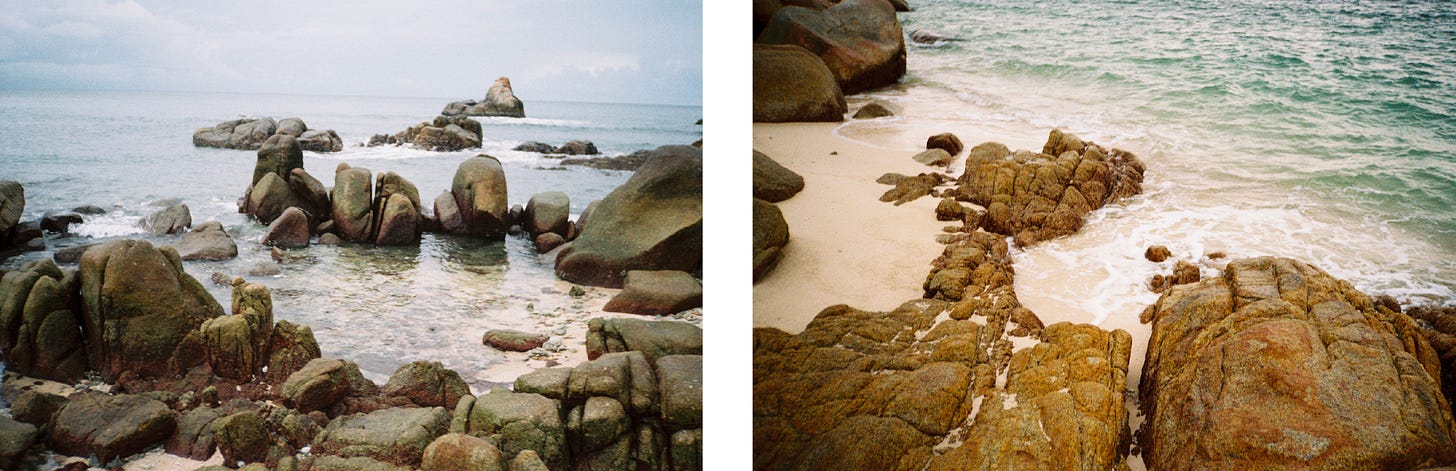

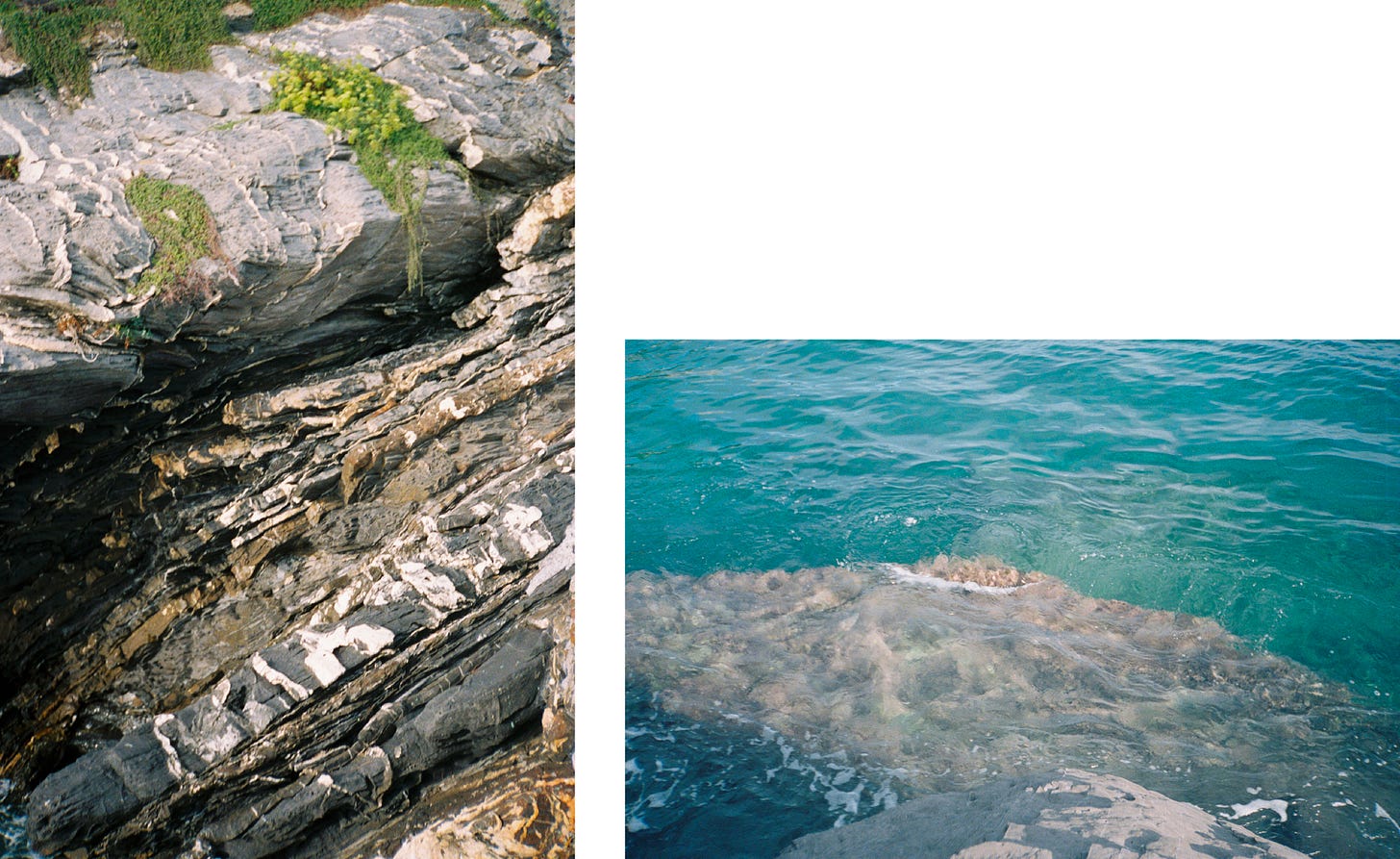

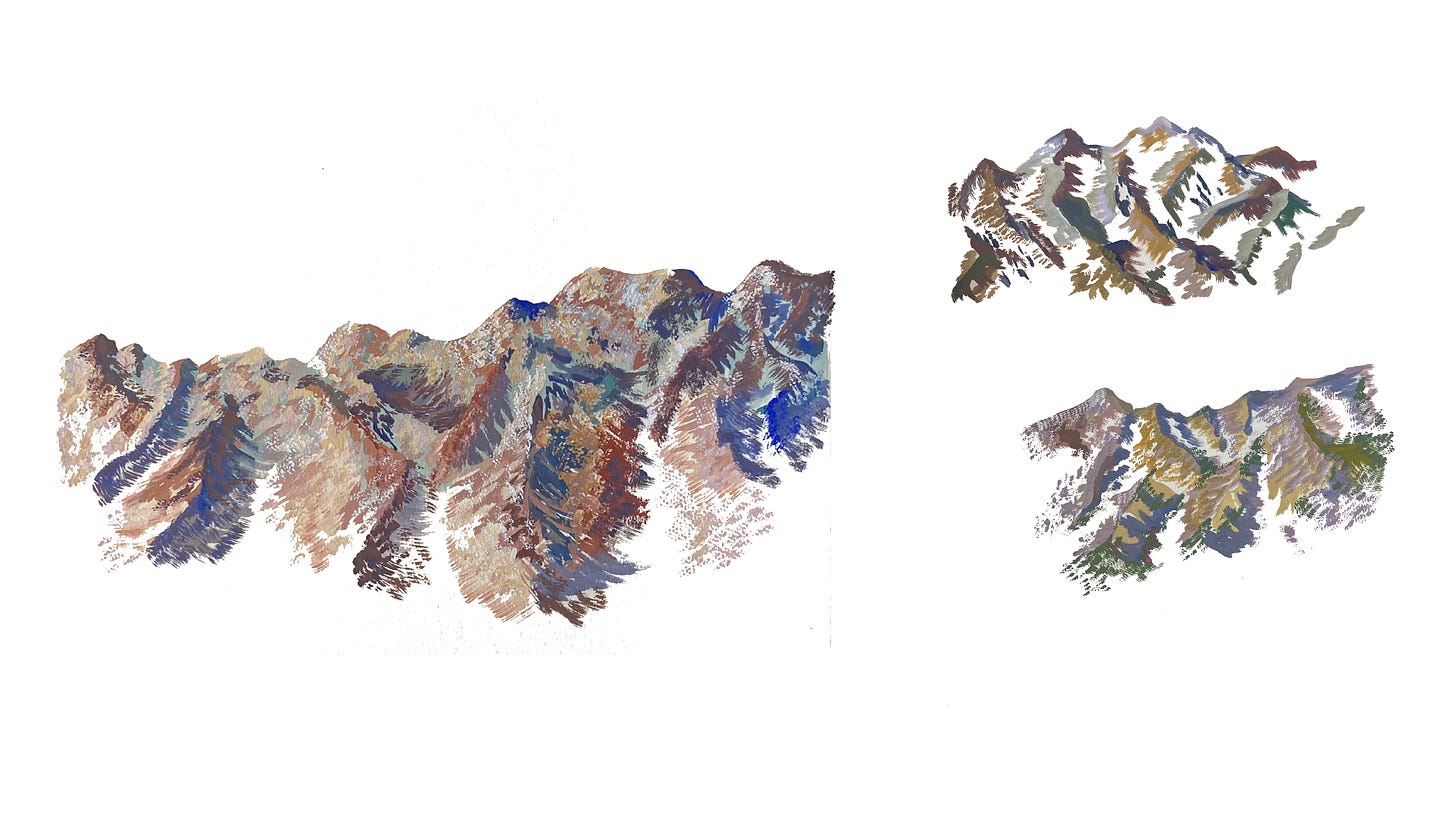

In drawing Oliveros and Eastman’s work, it is this improvisatory quality, the live dialogue and decision-making between performers, that is so compelling to try to depict. To the listener, the relative freedom appears rooted in a more solid structure, a shared roadmap for choreographed spontaneity. In the wake of these performances, I’m culling film photos from an archive built up over four years, thinking about fixity and fluidity, form and formlessness, perceived solidity and mutability, while absent-mindedly collecting photos of water and rocks. Last weekend, EL, NM, MT, BN, J, AX, and I have just returned from Anza Borrego. We hike by moonlight through the canyon until we encounter a cholla, our headlamps insufficient to guard against running into barbs in the dark. The next afternoon at the same place, we encounter a class of enthusiastic young geologists and their instructor, who explain the patterning of the canyon’s rock face towering above us, describe the carving and erosion, how this expanse of desert was all once underwater.

The bodies of water, rocks, their place names, their temporal context; the enormous walls of the canyon and the desert wind blowing between our bodies and up the rock faces; these give me the small-feeling, make me think of an accompanying lyric to an Arthur Russell melody that is often stuck in my head: “a pebble in a pool.” The small-feeling comes to me less frequently in the city. In the mountains and deserts and by the ocean and even on flat expanses of paved road, I find it’s more possible to seek out and sink into. By design, it’s difficult to feel connected in cities built on alienation, settler colonial displacement and erasure, the destruction of native plant life and the life forms supported by them when not crushed by asphalt and concrete.

“The first time I performed Eastman, I remember feeling like my brain was melting into everyone else’s brains,” my girlfriend tells me, who plays the show, and gets T and I into those seats behind the stage. MT’s depiction reminds me of Dustin Hoffman’s blanket scene from early aughts classic I Heart Huckabees, where existential detectives conduct an investigation on behalf of an indignant twenty-something environmental activist:4 “Oh, everything is the same even if it’s different.” “Exactly.” “I never feel more connected to the people—to the audience, to the other musicians—than when I’m performing Eastman,” MT tells me.

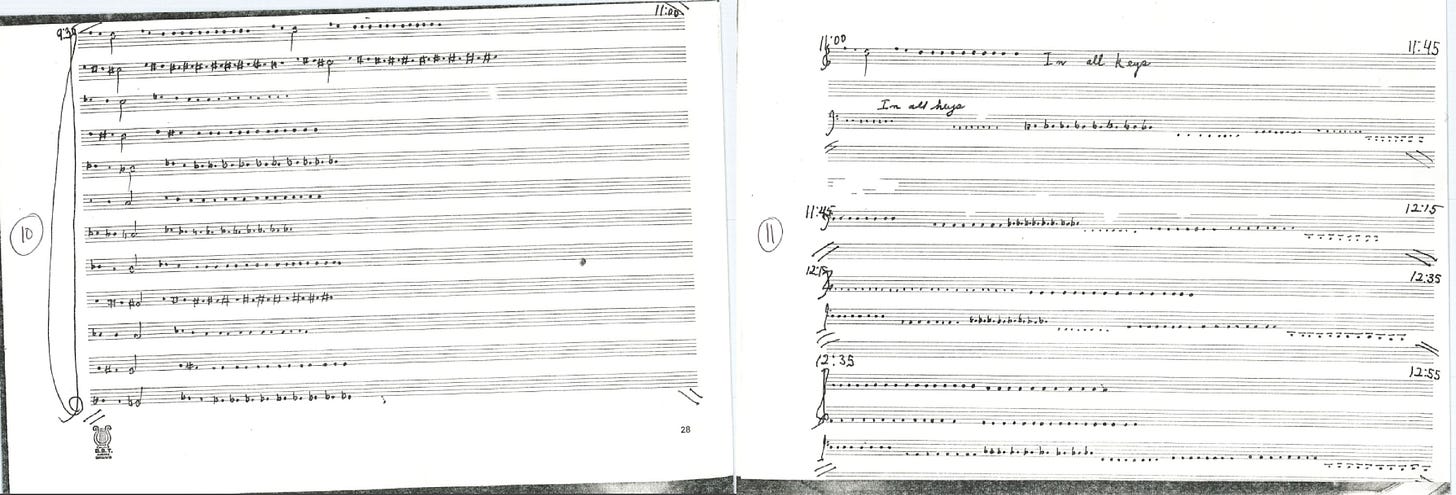

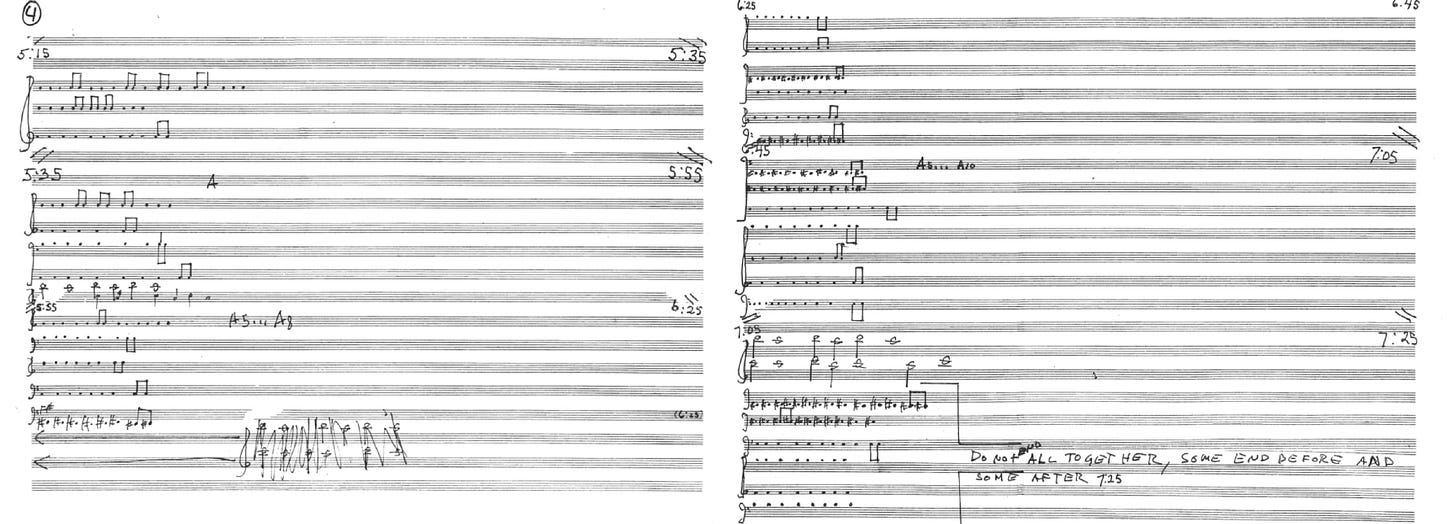

Over the course of his life and work, Eastman developed a compositional technique that he called organic music, a cumulative approach where the whole is developed through accumulation and disintegration:5 “They're not exactly perfect, but there is an attempt to make every section contain all of the information of the previous sections, or else taking out information at a gradual and logical rate.”6 MT pages through the scores7 to show us their characteristic sparse notation.8 That the work weaves improvisational interdependence, facilitated by cooperation, inventiveness, and flexibility on the part of individual musicians, strikes me as a kind of “calibrated imprecision.” In response to this characterization, MT underlines “the embrace of chaos, mess, and grit” inherent to this approach.

“He gives performers time codes where you know you’re doing one gesture, and it’s turning into another. But because he’s giving you this long period, maybe a minute to go from one gesture to another gesture, and then everybody is doing that at their own rate, what you get is something that feels like birds murmuring or like a school of fish…I think that’s why the pieces are so striking; they have this unique quality based on this one compositional idea.”9

I read that Eastman “conceived nearly all of his works for people he knew personally, his close friends and colleagues,” communicating instruction verbally and implementing “indeterminacy and improvisation as critical components [of performance].”10 For someone so committed to the ephemeral, to the performance as an exacting and irreplicable event, in his absence, there is arguably a great deal of room for misinterpretation in posthumous renditions of his work.

When he died in May 1990 at age 49, almost no one was informed of Eastman’s death. The Village Voice ran an obituary eight months later, which was the first that many friends and colleagues heard of his passing. Eastman had been unhoused for a decade, rumored to have briefly lived at Tompkins Square park after losing most of his possessions when he was evicted from his East Village apartment, including many of his scores.11 Mary Jane Leach, who set out to collect Eastman’s work in the late ’90s, describes meeting Julius in 1981: “while externally outrageous and almost forbidding, [Julius] was genuinely generous and warm, and not unkind. He was brutally honest…what it boiled down to was integrity. He had a radar that could detect bullshit (and there was a lot of that going around, a lot of posing.)”12 Poet R. Nemo Hill, a writer and an early lover of Eastman’s, describes that

“[Julius’s] categorical refusal to play by any rules he suspected of even the slightest infraction of his core principles, his refusal to obey any authority other than that which he had identified in his own conscience as the Law—this program was carried out with all the solemnity of a full-blown heresy against prevailing doctrine.”13

This commitment to the integrity and truth of his own subjectivity and perspective, to uncompromising self-expression, is legible in his compositional work, which demands the presence and perspective of the performers themselves. That Eastman’s work is generative and provocative, “minimal in form but maximal in effect,”14 is attributed partly to his wide-ranging influences as a composer and musician “working between Uptown and Downtown” New York in the ’70s,15 performing with the Brooklyn Philharmonic and experimenting with the underground scene.16 In a 1976 interview, Eastman stated “What I am trying to achieve is to be what I am to the fullest. Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, a homosexual to the fullest.”17

The stark bravado of Eastman’s uncompromising vision is evident in his notorious 1975 performance of John Cage’s Song Books. Eastman, who had performed the piece on Cage’s invitation before without incident, gave a provocative and explicitly sexual lecture, a campy critique spanning race, colonialism, and sexuality, inviting a man “Mr. Charles” and a woman “Miss Suzyanna” onstage. According to one review, “By the time Eastman’s little performance was finished, Mr. Charles was completely undressed, and Eastman’s leering, libidinous, lecture-performance had everyone convulsed with the burlesque broadness of his homoerotic satire.”18 Cage was enraged, uncharacteristically unrestrained in his denouncement of the performance, furiously accusing Eastman of being obsessed with his own sexuality.

I read a compelling argument by Toni Lester that takes the incident as a case study, opening from the perspective of intellectual property law and pivoting to consider what collaboration might have been possible “if the dynamic shifted from the adversarial to the relational” using “theories of trust and communication from the fields of feminist relational psychology, philosophy, and law.”19 Lester is forthright at the outset with her general sense that no, a trust-based dialogue would not have been possible between Cage and Eastman, both of whom “had fairly fixed views about the trajectory their art should take.” Lester nonetheless makes the case that greater attention be paid to “the role that power, privilege, racism, homophobia, and sexism play [between composer-authors and performers] otherwise, each side will continue to walk away feeling betrayed and devalued, respectively.”20

John Cage’s approach to his sexual orientation in his artistic persona differed distinctly from Eastman’s: “silence was a strategic aesthetic historically appropriate for Cold War America.”21 In his own words, Cage was a composer who wanted his art “to diminish…the ego and…increase the activity that accepts the rest of creation.”22

“For [Cage], the rest of creation was a nonpolitical space where the experiences of African Americans, gays, women, and other marginalized groups should not be highlighted. By taking this stance, however, he risked the all too frequent practice of people in majority cultures equating their concept of reality with actual reality.”23

Eastman, at this time, was developing a body of work that sought to “raise questions about racism, homophobia, and the power of words,” with titles that necessitated a language warning: Crazy N–, Dirty N–, Evil N–, N– Faggot, Gay Guerrilla.24 According to musical historian George Lewis, “the effects of Eastman’s confrontation with Cage proved to be a generational changing of the guard: His performance that day may have constituted an intersectional testing of the limits of his membership–or, in American racial parlance, his ‘place’–in the experimental scene.”25 In January 1980 during his composer residency at Northwestern University, Eastman introduced one piece by describing its title in detail:

“Now the reason I use Gay Guerrilla—G U E R R I L L A, that one—is because these names—let me put a little subsystem here—these names: either I glorify them or they glorify me. And in the case of guerrilla: that glorifies gay—that is to say, there aren’t many gay guerrillas. I don’t feel that ‘gaydom’ has—does have—that strength, so therefore, I use that word in the hopes that they will. You see, I feel that—at this point, I don’t feel that gay guerrillas can really match with ‘Afghani’ guerrillas or ‘PLO’ guerrillas, but let us hope in the future that they might, you see. That’s why I use that word guerrilla: it means a guerrilla is someone who is, in any case, sacrificing his life for a point of view. And, you know, if there is a cause—and if it is a great cause—those who belong to that cause will sacrifice their blood, because, without blood, there is no cause. So, therefore, that is the reason that I use gay guerrilla, in hopes that I might be one, if called upon to be one.”26

Eastman emphasizes the instructive role of individuated identity across his work, which takes seriously his own subjectivity, and here also strives toward group formation and building solidarity. Connectivity is predicated on situating oneself in context, rather than on a contrived, new age, fictional universalism. For the purpose of her argument, Lester refuses to examine Cage’s right to his work “as if it were a piece of property,” speculating instead “what current and future collaborations between artists might look like if [trust-based dialogue] were adopted now.” Her focus on the relational rather than the proprietary reminds me of philosopher Simone Weil’s emphasis on “human obligations” rather than “human rights.”27 Weil insists on obligation, on commitment to fulfilling the base spiritual and moral needs of our neighbors, which should hold more weight than rights, which are merely codified by law: “Paying attention is one of our most fundamental obligations.”28

At a friend’s picnic birthday last week at the park, we all read a set of instructions printed on half sheets of paper and lie down in the grass, a circle in the gathering dusk, our heads pointed inward toward each other, faces to the sky, hands on the abdomens of the two people next to us. The instructions are simple and the outcomes unpredictable, we synchronize our breathing and harmonize tones, bridging different points on the circle at different times, each action a little bit purposeful and a little bit up to chance, until it feels done and we stop—I notice there is now a mosquito trapped between my face and eyeglasses.

As someone who doesn’t perform or practice music, it’s my first time playing an Oliveros score. Scholars of her work have noted that “intuition” is coded by the dominant patriarchal culture as “feminine” in opposition to the “conventional [norms] of contemporary music such as an overriding concern for form, size, unity, and complexity.”29 I think of Eastman’s 1974 work Femenine, an “immersive, jazz-inflected chamber piece which slowly builds into a textured soundscape,” which he would perform wearing a dress.30 In one rendition of Femenine in Albany, Eastman wore an apron over his dress and served a soup he had cooked to the audience for the duration of the performance.31

In their very construction, Oliveros and Eastman’s scores encourage contextual understanding of both their personhood and larger body of work. At MN’s for hotpot sometime after the Eastman Russell performance, we speculate about how the historically marginalized work of artists gains traction after their deaths. The posthumous renditions provoke questions about authorship and integrity, implicating performers and directors, cash flows and accolades. When I consider that creative expression necessitates citation and reference, connection and bridging, between different forms across spatially- and temporally- diverse contexts, I invariably think also of the historic and ongoing violence of extraction.

In drawing up roadmaps for choreographed spontaneity, what facilitates connection is grappling with the real limitations of perspective. Improvisational interdependence requires a collaborative trust built up over time. Most conversations I’ve had in recent months–in the wake of the fires, in the wake of the presidential inauguration–in some way strategize around the need for progressive or leftist groups to bridge and connect. Oscillating between the seemingly-solid structure or safety of various identity groups and a broader collective loosens diaphanous borders into an unfixed form.

“We open in order to listen to the world as a field of possibilities and we listen with narrowed attention for specific things of vital interest to us in the world. Through accessing many forms of listening we grow and change whether we listen to the sounds of our daily lives, the environment, or music. Deep listening takes us below the surface of our consciousness and helps to change or dissolve limiting boundaries.”32

Alan Baker. “An Interview with Pauline Oliveros.” January 2003. American Mavericks. American Public Media.

Pauline Oliveros and Fred Maus. “A Conversation about Feminism and Music.” Perspectives of New Music 32, no. 2 (1994): 174-93. https://doi.org/10.2307/833606.

Sarah Totty. “About Pauline Oliveros.” Long Beach Opera program notes, 2024-2025 season All Oliveros.

I Heart Huckabees. 2004. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSdrwqLUpD0

LA Phil. March 2025. Walt Disney Concert Hall 2024 /25 Season.

Tom Huizenga. “Julius Eastman, A Misunderstood Composer, Returns To The Light.” NPR All Things Considered. 21 June 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/deceptivecadence/2021/06/21/1007150496/julius-eastman-a-misunderstood-composer-returns-to-the-light

Evil N– Julius Eastman 1979. Wise Music Classical. https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/57876/Evil-Nigger--Julius-Eastman/

Gay Guerrilla Julius Eastman 1979. Wise Music Classical. https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/57877/Gay-Guerrilla--Julius-Eastman/

New Amsterdam Records. “Let’s talk about Wild Up and Julius Eastman: “What I am trying to achieve is to be what I am to the fullest. Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, a homosexual to the fullest. - Julius Eastman”” 5 July 2024. https://newamrecords.substack.com/p/lets-talk-about-wild-up-and-julius

Femenine Julius Eastman 1974. Wise Music Classical. https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/57875/Femenine--Julius-Eastman/

Jeanne Claire van Ryzin. “Julius Eastman to The Fullest: For its annual Pride Concert, Austin Chambers Music Festival presents “Femenine,” a masterpiece of the late queer, Black composer who was once all but forgotten.” Sight Lines: Arts, Culture, News, & Ideas. 5 July 2018. https://sightlinesmag.org/julius-eastman-to-the-fullest

Mary Jane Leach. “Continued from Projects page.” 2019. https://www.mjleach.com/eastman.htm

R. Nemo Hill, The Julius Eastman Parables, in GAY GUERRILLA: JULIUS EASTMAN AND HIS MUSIC 83, 89 (Packer & Leach eds., 2015).

Leach. “Continued from Projects page.”

Andrew Male, Julius Eastman: The Groundbreaking Composer America Almost Forgot, THE GUARDIAN (Sept. 14, 2016), https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/sep/14/julius-eastman-american-composer-pianist-femenine [https://perma.cc/NJX8-62WJ].

Ryan Dohoney, John Cage, Julius Eastman, and the Homosexual Ego, in TOMORROW IS THE QUESTION: NEW DIRECTIONS IN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC STUDIES 39, 43 (Piekut ed., 2014).

Renate Strauss. “Julius Eastman: Will the Real One Stand Up?” Special to Buffalo Evening News. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/536c0186e4b0f62696d3c528/t/561194d1e4b0b3f00aaad7d0/1443992785379/Julius+Eastman_will+the+real+one+stand+up.pdf

Marke B. “The Song Books Showdown of Julius Eastman and John Cage: Remembering an incendiary performance by the radical composer that shook up the avant-garde.” 12 July 2018. RedBull Music Academy. https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2018/07/julius-eastman-john-cage-songbooks

Dr. Toni Lester. “Questions of Trust, Betrayal, and Authorial Control in the Avant-Garde: The Case of Julius Eastman and John Cage.” Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2019. 11 March 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3547227

Lester. “Questions of Trust, Betrayal, and Authorial Control in the Avant-Garde: The Case of Julius Eastman and John Cage.”

Dohoney. John Cage, Julius Eastman, and the Homosexual Ego.

Marc Thorman, John Cage’s “Letters to Erik Satie,” 24 AMERICAN MUSIC 100 (2006).

Lester. “Questions of Trust, Betrayal, and Authorial Control in the Avant-Garde: The Case of Julius Eastman and John Cage.”

Huizenga. “Julius Eastman, A Misunderstood Composer, Returns To The Light.”

Erik Morse. “The Radical Queerness of Julius Eastman.” Vogue. 24 June 2021. https://www.vogue.com/article/julius-eastman-wild-up-femenine

Gay Guerrilla Julius Eastman 1979.

Simone Weil. L'Enracinement, prélude à une déclaration des devoirs envers l'être humain. Gallimard: Collection Espoir. 1949.

Robert Zaretsky. “What We Owe to Others: Simone Weil’s Radical Reminder.” The New York Times. 20 February 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/20/opinion/simone-weil-human-rights-obligations.html

Timothy D. Taylor. “The Gendered Construction of the Musical Self: The Music of Pauline Oliveros.” The Musical Quarterly. Vol. 77, No. 3 (Autumn 1993) pp385-396. Oxford University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/742386

Huizenga. “Julius Eastman, A Misunderstood Composer, Returns To The Light.”

Morse. “The Radical Queerness of Julius Eastman.”

Pauline Oliveros. The Center for Deep Listening. https://www.deeplistening.rpi.edu/deep-listening/