If I were to trace for you my longtime preoccupation with monks and nuns, it would go something like this: images of Salzburg landscapes and Julie Andrews’ voice on VHS tape; Winona Ryder as a convent-obsessed petulant preteen playing across Cher and Christina Ricci in 1990 film Mermaids; the illuminated manuscripts on view at the Getty when I was nine years old, which SC specifically took me to see less for the content but moreso to match the obsessive precision she saw in the detailed drawings and tiny writing of my compulsively-kept childhood notebooks; the lyrics to 1982 Sisters of Mercy track Adrenochrome; Pedro Almodóvar’s Dark Habits; a beer made at a trappist monastery; the bikeride from Brooklyn across Manhattan, through Central Park and out to the westside, tracing up the Hudson in heavy summertime humidity to the sprawling green lawns of the Met Cloisters.

What I romanticized about a monastery was the idea of a communal life committed entirely to artistic work, research and mapping, writing and drawing: total devotion to process, not preoccupation with end product. I didn’t factor in faith or fully register that religion was implicated. From a young age, I had compartmentalized all manner of organized religion as insidious and deceitful: it enables people to follow doctrine without critical thought, eliminating dissent and productive friction; colonizes and enacts genocide on indigenous populations through proselytizing missionaries and land theft on behalf of empire; foments fundamentalist ideology and harassment, threat, and harm to gay, trans, gendered, and racialized bodies globally; gives individuals permission to divest from the material and interpersonal obligations of shared life on this one earth through apocalyptic fantasies and fixation on an imagined afterlife. I had very little tolerance for shared belief systems.

In the interstitial time between the fires and the militarization of police-aided and abetted immigration and customs enforcement raids across the 88 cities of LA county, I’ve been thinking about the difference between organized religion and amorphous spirituality, the purpose of shared belief in motivating coordinated action, the use of narrative in service of collective movements, how storytelling can provide a shared framework for a diverse group. In working class black and brown immigrant communities across LA, I see substantive solidarity at work within congregations, and between people of differing faith traditions. The small-scale organizing and bridging between historically siloed belief systems makes me speculate about the possibility of storytelling and shared ritual for an increasingly expansive ideology—for land back, indigenous sovereignty, shared stewardship of this one earth, liberation for all beings.

I first encounter geographer Linda Quiquivix’s work in meatspace—in physical space, in person—at “autonomous, local, community space inspired by the Zapatista movement” Eastside Cafe in El Sereno two years ago in october.1 Quiquivix reminds us that to secularize something that isn’t secular is dangerous. “If we don’t talk about spirituality, ‘ideology,’ ‘religion,’ ‘philosophy,’ or whatever you want to call it, whatever guides your life ethos, if we don’t understand our ethics, how we understand time and space, how everything dies,” if we don’t talk about that dimension, Quiquivix reminds us that the secular embrace of capitalism in “the west,” or any other dominant system, will do it for us. A stubborn refusal to acknowledge religion throughout my twenties did nothing to undo or mitigate historic and ongoing harms, and still I am constantly identifying dominant systems that have filled gaps in my own ethic.

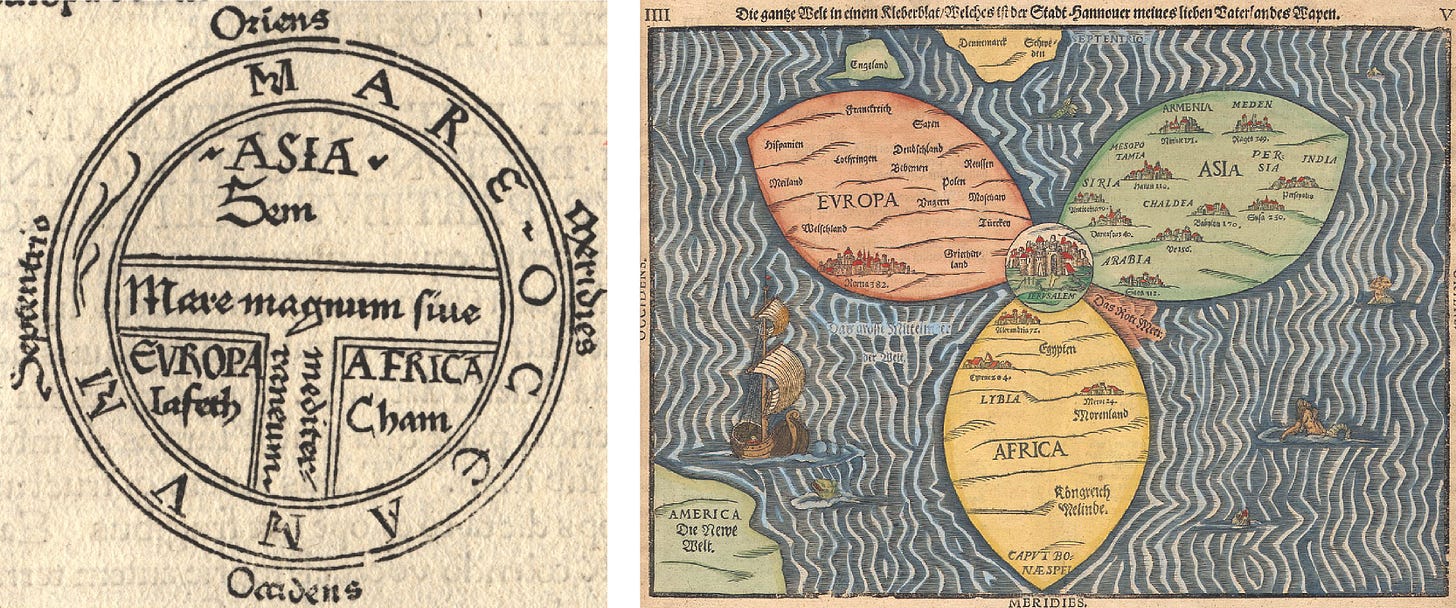

Quiquivix analyzes maps to illustrate that biblical storytelling has been embedded in european cartography. The “very anti-Black narrative” of Cham as the “cursed” son of the biblical Noah, tasked with populating the african continent after the flood, was later inscribed onto a medieval map because of 19th century race science coming out of europe. “Semite” refers to the sons of Sem, a word still used to designate that people of the asian continent do not belong on the european continent—though we know there are not two distinct continents, there is one continent: eurasia. On another map almost one thousand years later, Quiquivix notes that europe is still colloquially referred to as “the west” because it is drawn “west of jerusalem,” located at the global center. Physical realities are subverted by religious ideology.

These days, we’ve all got a little map in our pocket, on our phones. So much of the knowledge that we hold in common relies on place names and spatial delineations drawn by colonial conquest, and changing at the whim of corporations: it’s the gulf of mexico today, tomorrow the gulf of america. Borders have never made a people or a place safe, Quiquivix reminds us. “Borders are agreements between the invaders, so that they don’t fight; between the plantation overseers, so that they don’t interfere with each other.”2 Property does not concern itself with the well-being of anyone or anything within that drawn line. In her book spanning “narratives of childhood in the Caribbean, journeys across the Canadian landscape, African ancestry, histories, politics, philosophies, and literature,” Dionne Brand writes

Too much has been made of origins. All origins are arbitrary. This is not to say that they are not also nurturing, but they are essentially coercive and indifferent. Country, nation, these concepts are of course deeply indebted to origins, family, tradition, home. Nation-states are configurations of origins as exclusionary power structures which have legitimacy based solely on conquest and acquisition.3

Quiquivix reminds us that in “the west,” where capitalism is one dominant ideology, a common narrative tells of Columbus colonizing the americas for riches. This motivation was secondary; his colonial conquests were fueled primarily by extremist religious convictions, detailed in his 1502 manuscript Libro de la Profecías.4

Christopher Columbus was a very devout Catholic from above, with an apocalyptic vision, and a specific interpretation of a prophecy of the end of the world, that it would take place in Jerusalem…This might seem familiar if you know Christian zionism? Yeah? Still today. Columbus had this same worldview.5

To a room of housing justice workers and tenant rights organizers in early may, journalist Naomi Klein articulates an ideology shared between Christian zionists and tech billionaires today, in 2025, as “earth abandonment.” In a recent piece co-written with Astra Taylor, Klein describes this ideology as “end times fascism,” where the right has provided a narrative “that gives people permission not to care” about our shared home, this one earth. The seemingly inexplicable coalition between housing-insecure, financially-burdened workers and the super wealthy that elected Trump parallels a throughline between Christian zionist and tech billionaire storytelling.

Christian ideology commonly indoctrinates young people into preoccupation with an imagined afterlife, encouraging destruction through the narrative of the biblical rapture, or dissociation to survive in a world where racial capitalism mass produces instability and insecurity. This same disinvestment from the earth and detachment from this one life is reflected in tech billionaire investment in AI technology—which seeks “to sacrifice this animate world to build an artificial world,” and space exploration—which diverts attention and resources from the urgent need to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and stop global warming.

Interestingly, at a time when previously secular Silicon Valley elites are suddenly finding Jesus, it is noteworthy that both of these visions—the priority-pass corporate state and the mass-market bunker nation—share a great deal in common with the Christian fundamentalist interpretation of the biblical Rapture, when the faithful will supposedly be lifted up to a golden city in heaven, while the damned are left to endure an apocalyptic final battle down here on earth.6

Of the apocalyptic storytelling told by “end times fascism,” Klein says “it’s not that different from the celebrities who hired private firefighters to protect their private property—that’s the rapture here on earth.”7 Klein traces the destruction, mutual aid relief efforts, and subsequent police crackdown and encampment sweeps that followed in the wake of the Paradise fire near Chico in 2018 to chart a course for policy change and protections here in Altadena. When Klein calls for a narrative “in defense of deep beauty,” describing the “spiritual calling of what it means to commit to this place, not some afterlife but this one earth,” I think of Quiquivix’s charcoal drawings and maps of Aida camp in occupied Palestine, and global maps that draw out a connection to Zapatista organizing in Chiapas, connecting struggles for indigenous sovereignty to chart a way forward.8

Quiquivix orients her book around a compass, the Maya cross. “When we do ceremony,” she describes, “this is an altar, we have it on the floor, we place our offerings. We begin with the east, which is red, then we go west, which is black, south, yellow, north, white, and each has significance–” The physical to the east, spiritual to the west, emotional to the south, mental to the north. “There are seven cardinal directions in Maya geography: east, west, north, south, sky, earth, and at the center there is you, me, us, we’re in it.” The cross serves as a guide, as a “critique of colonial geography that places the viewer above the land as if they’re not part of the land, and then cuts it up into property, without realizing that is hurting even oneself.”9 Quiquivix notes that many first peoples orient an internal compass and sacred geography first to the east, toward dawn, a new day.

Reading a book structured around this interconnection between a place, people, and nonhuman inhabitants reminds me of a qigong exercise taught last month by a friend KY, whose butoh teacher had taught it to them, partly adapted from a Cherokee movement worker who had shared it with her. Barefoot on a blanket with J and DY, we physically direct our energy first to the east, to new possibilities, dawn, and a new day, then gesture west toward memory and history, wisdom and experience. The relationship between opposing directions is co-constitutive; one does not exist without the other. There is a push pull between youth and innocence to the south, and elders and ancestors to the north, reciprocity and duality to teaching and learning. Humor and levity, too, “we acknowledge the challenges our ancestors endured so that we could complain about microaggressions todayy—!”

The following week, KY and I go to tai chi at the temple in little tokyo. One of the aunties directs me to a sign-in sheet, offers us a bowl of freshly-washed grapes, unhesitatingly warm and welcoming, direct and no-nonsense. She reminds me so much of my auntie P, of my extended chosen family at the temple in Berkeley and the annual camping trip that tethers me to spiritually-centered interdependence, the deep beauty of this one earth, ritual practice and communal construction of meaning without fixed form or exclusionary boundaries.10 The towering sugar pines and four bodies of water that we visit every year—the lake, the caves, the creek, the river—tether me back to myself, to my physical body, and to the communal, to what we regard as sacred in this place and in each other.

At the height of pandemic lockdown, I haven’t been on the family camping trip in years and am living alone in Philly. I get laid off from a job at an architecture firm days after challenging my employers and coworkers on their strident defense of private property. I explain that the graffiti and barricades built up in the streets function in defense of life, in defiance of the police state, in protest against the murder of Walter Wallace. Yes, real people bear the real cost of these damages, but acts of property destruction must be understood as fundamentally nonviolent, as a desperate and direct defense of people and place. The concept of property positions itself against people and place spiritually, materially, physically, philosophically.

During the winter, I work on projects, live off food stamps, volunteer with west philly food not bombs, eat crates of chard foraged from the produce market parking lot. During the spring, I make drawings, weed, water, and dig in the dirt as an artist in residence at a farm in Roxborough, a bikeride north along the Schuylkill from my west philly apartment, run by friends who are dancers and doulas, committed to providing for postpartum mothers.11 AM and EV teach me to help with a planting of the three sisters for the first time: corn, squash, and beans growing together. I remember AM, at the end of that summer, conducting an audio project by asking friends what it might look like to “become indigenous.” I was put off by the phrasing, which centers identity rather than knowledge, semantically suggesting a disavowal of history and family lineage. The provocation still haunts me whenever I think about disentangling fixed identity from historic injustice, staying centered on experience and impacted people in our knowledge-sharing practices and forward-facing imagination.

Resistance to the ongoing raids in Los Angeles has been mobilizing for a week in earnest. Coordinating around a chaotic schedule of performance, rehearsal, meetings, direct actions, protests, prayer vigils to the federal building, and marches organized downtown, on sunday morning, early, I take MT to the mountains. For two days, we seek out bodies of water. We sleep under the redwoods and I concern myself only with what I can hear, perceive: the sound of a mother bird’s wings regularly entering and exiting the hollow of a redwood tree four feet from where we’re sleeping, the sound of the creek tracing a path down the slope over the rocks. After we’ve spent the day on mossy rocks at the base of the falls, I draw a prayer occasioned by the water, MT napping in the tent next to me, the golden hour falling on us through the redwoods. We resource ourselves by staying close to the trees.

Back in the city, I bike the LA river Paayame Paxaayt in the early mornings, at dusk, at the golden hour, tracing along the channelized concrete banks, plant life and moss growing up through cracks in the paved surface littered with debris. The soft bottom of the river has been breaking up the concrete here, reminding us that it’s possible to liberate our waterways, ourselves. I think of a Toni Morrison excerpt from her essay The Site of Memory,

You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. “Floods” is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.12

On a full moon bike ride two years ago with Coyotl Macehualli, whose Takaape’ Waashut festivals and bike rides13 are organized to protect California’s endangered native black walnut trees,14 culture bearer of Gabrielino Tongva, Chumash, Yoeme, and Chicana descent Tina Calderon joins up with us to orchestrate a group conversation at the park. Everybody shares a little about how they are situated in this place.15 Calderon, whose work includes preservation of ancestral Tongva and Chumash language through song, reminds us Paar'e 'eyooxaarin xaa, “water is life: it’s time we respect water as the living relative and powerful spirit that it is.”16

The call to “be water” has stayed front-of-mind for me lately, from Hong Kong protestors in 2019, popularized by Bruce Lee, derived from Laozi’s Tao Te Ching dated at roughly 400 BC, which in romanized translation is often referenced both as philosophy and as religious practice. In one interview, protestors describe

We wanted a decentralized political movement. The Umbrella movement in 2014 was centralized, with leaders who were targeted by the regime. There were arguments and disagreements. It wasn’t effective, it led to a dead end. In 2019, the idea “be water” became the movement’s philosophy. During protests, strategies and decisions evolved organically, there was collective decision making. People protesting in one area would suddenly move to another location. It was so fluid the police couldn’t catch them.17

We grew up with a wing chun dummy on the back patio of my childhood home, its stubby wooden arms reaching out when I’d walk past or pretend to fight it as a kid. CC studied for many years under Guru Dan at the Inosanto Academy in the art and philosophy of 截拳道, jeet kune do, which roughly translates to “stop fist way” or “way of the intercepting fist,” Bruce Lee’s school of martial arts.18 In the 60s it was ahead of its time, but now, this is standard for mixed martial arts, CC patiently reminds me, having explained this many times to me over decades. The practice of jeet kune do draws from a multitude of different art forms—wing chun, tai chi, muay thai, jiu-jitsu, savat—you pick what’s best for your physiology and natural attributes. “Take what’s useful and leave what’s not,” SC summarizes.

The incorporation of many different art forms into one mutable, unfixed form for fighting and self defense is material and literal, not metaphoric, but as a broader philosophy, as a religious principle, as an organizing ethic; we shouldn’t lose our individuated shape in order to fight side by side, we should be able to coordinate and move fluidly with all our differences contained. In my experience, primarily within self-described “leftist” spaces at the heart of US empire, this is more challenging in practice. The philosophy and practice of jeet kune do reminds me of a January 2013 Zapatista communique:

Our analysis of the functioning, strengths, and weaknesses of the dominant system has led us to believe and to emphasize that unified action is possible if we respect what we call the “modos” [manner, way of doing things] of each of us.

And these things we call “modos” are nothing but the knowledges that each of us, individual and collective, have of our own geography and calendar. That is, of our pains and our struggles. We are convinced that any attempt at homogeneity is no more than a fascist effort at domination, regardless of whether it is hidden in revolutionary, esoteric, religious, or any other language.

When one speaks of “unity” they elide the fact that such “unity” occurs under the leadership of someone or something, be it individual or collective.

On the false alter of “unity,” not only are differences sacrificed, but the survival of all of the small worlds under tyranny and injustice they suffer is obscured.

In our history, this lesson is repeated time and again. And every time the world turns, our place is always that of the oppressed, the disdained, the exploited, the dispossessed.

What we call the “four wheels of capitalism”: exploitation, displacement, repression, and disdain, have been repeated throughout our history, with different names up above, but we are always the same ones below.

But the current system has gotten to a state of extreme madness. Its predatory ambition, its absolute disrespect for life, its delight in death and destruction, and its effort to impose apartheid on all of those who are different, that is, all of those below, is taking humanity to the point of disappearance as a form of life on the planet.19

Origins. A city is not a place of origins. It is a place of transmigrations and transmogrifications. Cities collect people, stray and lost and deliberate arrivants. Origins are rehabilitated and rebuilt here.20

If the city trades connection with the land for a diversity of people in close proximity, this is a grace of migration and freedom of movement. Dionne Brand’s writing explores the search for place and belonging, and identifies the specific dispossession and displacement of the Black body within global histories of enslavement and the erasure of lineage and history. Her poetic and narrative work expands to criticize broadly any tightly-defended fixed identity or singular definition of culture.

Too much has been made of origins. And so if I reject this notion of origins I have also to reject its mirror, which is the sense of origins used by the powerless to contest power in a society. The overstrong arguments about “culture,” which are made both by defenders of what is “Canadian” as well as defenders of what is labelled “immigrant.” These are mirror/image-image/mirror of each other and are invariably conservative. Because they must draw very definite borders both to contain their constituencies as well as, in the case of the powerful, to aggressively exclude the other and, in the case of the powerless, to weakly do the same while waving a white flag to the powerful for inclusion.21

This description “mirror/image-image/mirror” recalls Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World, which lays out the consequences of commodifying our identities online.22 The book describes how sourcing our news in algorithmic echo chambers has increasingly siloed not only the “left” and “right,” but countless subsets of both into such calcified antagonistic positions that everyone is left increasingly alienated and disempowered. Ryan Coogler’s Sinners offers a different provocation around duality as antagonistic or oppositional, rather than co-constitutive and interconnected. Coogler employs light and dark, heaven and hell, saved and sinned, building and unbuilding, connection and alienation, black and white, the dead and the undead, to explore the vampire as an allegory for assimilation and appropriation, goaded on by organized religion, colonization, and spiritual bypassing.

I read journalist Erin Aubry Kaplan on the first american pope’s afro creole ancestry and finish reading Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s Elite Capture the same day that I see Sinners in theaters. Kaplan specifies that this new pope “personally knows all about the hypocrisies, lies, and fear that built america’s racial hysteria,”23 and describes two realities existing side by side: “an ancient, all-powerful church that was part of the racial elite that made life in the American South so suffocating for people of color. Yet in their insulated neighborhoods Creoles made the Catholic Church into a community institution that was as culturally Creole as red beans, jambalaya, and Mardi Gras.” In my work the past three years designing affordable housing on congregation-owned land across LA county with a multiracial, multifaith community organizer,24 I am constantly surprised to encounter a church “from below” rather than “from above,”25 learning all the time what forms of work are possible from this place.

I write this now as a reminder to myself and maybe to you: mirroring and defining oneself in contradistinction to the other is easy. The reciprocity of teaching and learning, listening, discerning where difference is generative rather than extractive or destructive, parsing whether there is or isn’t generative possibility, is harder to practice. Barely half a year since the fires hit LA, we organize a march in Altadena and North Pasadena, rallying for a just recovery centering the needs of Black longtime residents. I read my coworkers a June Jordan poem, “a short note to my very critical and well-beloved friends and comrades,” to foreground the effort of bridging across our different approaches, priorities, inclinations, commitments.

First they said I was too light

Then they said I was too dark

Then they said I was too different

Then they said I was too much the same

Then they said I was too young

Then they said I was too old

Then they said I was too interracial

Then they said I was too much a nationalist

Then they said I was too silly

Then they said I was too angry

Then they said I was too idealistic

Then they said I was too confusing altogether:

Make up your mind! They said. Are you militant

or sweet? Vegetarian or meat? Are you straight

or are you gay?And I said, Hey! It’s not about my mind26

June Jordan, whose work stayed spiritually grounded in justice, famously called on us to remember that the fight for Palestinian liberation is a litmus test for morality of our time.27 We’ve got to get grounded in our commonalities wherever possible, in the materiality of our relationships, rather than reducing each other to metaphor or symbol, defining and representing ourselves in opposition.

Fired up about something the other morning, I share with KY that I tend to have a litigating attitude. We’re discussing the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh and deer park monastery, and I note that monks do not have a litigating attitude. I would like to be like a monk, I would like not to have a litigating attitude. Cornel West reminds us to root everything we do in love. Simone Weil emphasizes human obligations rather than human rights. Care should be our spiritual center, lawfulness or unlawfulness is completely beside the point. I repeat the aphorism to myself—monks do not have a litigating attitude—anytime I pinpoint frustration or impatience toward someone who I know is on my team, in this fight alongside me, side by side and to the left.

In the first week of april, my mom’s highschool boyfriend’s sister MY remembers about my rogue interest in the life and work of sister Corita Kent. After the breakup, SC had remained part of the highschool boyfriend’s family. His sisters CL, MY, and the youngest, EI, who is also a writer and artist, have always been aunties to me, their kids an additional set of cousins, the corners of their mom DR’s house as familiar to me as my own grandmother’s house. In the apartment complex where my parents lived until I was a toddler, EI once held a gallery show in the room downstairs entitled “Disasters,” featuring mummies and fires in the city of Los Angeles. SC, MY, and DR have an extra ticket to the Corita art center today, will I come meet them downtown?

Only MY notices that EI is calling DR, so she picks up the call. The Chicago Federation of Labor, Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, and others have organized a protest today against cuts to government jobs, shuttering of federal agencies, deportation of immigrants, and imposed tariffs.28 EI shows us her sign,

TO DO:

PROTEST

DO LAUNDRY

CALL MOM

BE BRAVE

MY describes how, growing up, DR would “papier-mâché all the kitchen cabinets, and some of the furniture.” “I took them to Watts Towers all the time as kids,” DR tells us matter-of-factly, “that’s where I got all my ideas!” Found objects, collaboration with the intuitive creativity of neighborhood kids, collected refuse and detritus from the interstitial recesses of the city, these were instilled as family values. DR studied history as a young mom in her twenties at Immaculate Heart College, where Corita taught art. Going through the archives at the art center, DR tries to identify artists and students in the photographs, blurry faces wearing habits, and raises an eyebrow to us, “some of us in the history department had the idea that they could be a little more precise about putting down everybody’s names!”

DR describes that Corita taught students how to look, how to see for themselves, that she encouraged them to adopt a critical lens.29 What I find compelling in Corita’s work is her adoption of the pop art aesthetic of Warhol and his contemporaries with none of the ironic detachment.30 Corita’s work employed “the same repetition and visual potency of everyday consumerism,” but was sincere in its assertion of civil rights and protest of social injustice. Corita became increasingly critical of institutions, her artwork openly condemning racial injustice and police brutality in the US, opposing the war in Vietnam, and supporting farm workers movements, and she left the Catholic church in 1968. She befriended Harvey Cox, whose book The Secular City promoted “turning [one’s] attention from worlds beyond and toward this world and this time.” Cox argued for a Christianity focused on this life, on this earth.

Encountering stories of Corita’s work as a teacher through DR, also a teacher, with my mother SC, also a teacher, underlines the importance of young people having their creative worlds supported and bolstered. It’s reminding me, too, of how materially supported we were at the encampments last year, with space to learn together, share resources, alongside students, teachers, community members, other housing justice organizers. The importance of assembly and house meetings, planning for the slower, intentional, imaginative, creative, proactive work of birthing a new world has been weighing heavy in several conversational spaces and affinity groups the past two weeks, many of us mobilizing repeatedly but struggling to carve out the time to strategize. In her recent book Wave of Blood, Ariana Reines reminds us

The heart must open. And practice with this has to be undertaken by artists.

The works of art that we see nowadays, that are pervaded by a consciousness that is not incoherent or reactive are relatively few.

We make a mistake I think when we focus our energy on denouncing and pulling down, and a libidinal investment in heaping our disgust on everything that is so wrong, and I am not denying the wrongness.

The way the future has always come is people start building it before the bad stuff is over. One has to divest from dystopia, one has to divest from the libidinal surge of righteous superiority.

We all feel it and we all experience the need to separate ourselves somehow (even if only internally) from the kind of moral destitution, the vicious mindlessness soullessness we see everywhere–but it has to be done without ourselves turning into the very thing we hate.

Negation is spiritual death, a coworker reminds us. We have to be disciplined about putting our energy toward the construction and creation of this new world, frame out in the positive what we want to see, and put our physical bodies where they need to be to enact it. “Don’t try to create and analyse at the same time. They’re different processes,” Corita’s art department rules remind us [me, writing this, to you]. What keeps me spiritually centered is the new world we are building together: AD’s “Beauty is Emergent” to accompany HN’s “Migration is Sacred” artwork in support of a fund to support landscape construction and maintenance worker’s lost wages, Ktown for All’s vendor buy-out efforts that have inspired the same in Chinatown, Altadena and Pasadena, and across the South Bay, everyone buying groceries for their at-risk neighbors and patrolling their local neighborhoods from the home depot parking lot.

Two weeks ago saturday, a broad contingent of corporate partners—some of them openly zionist, all of them assuredly fueling climate change and exacerbating environmental racism—sponsor a nation-wide “protest” against the current US administration. The “protest” likens the administration to a monarchy, focusing disdain on a single individual, which obscures the more complex reality and refuses to name or condemn the many factors that have led to the bipartisan concentration of power and wealth destroying our shared home, this one earth. These “protestors” are encouraged to “sign up,” creating a codified list of names in a time of heightened digital surveillance and documented abduction of our neighbors. 11 million people show out, verging on the 3.5% of a national population that, under a range of different circumstances, has historically ensured success for nonviolent civil resistance movements between 1900 and 2006 fighting for regime change.31

I spend the day instead in Ktown with tenant organizers patrolling the home depot parking lot32 and in Chinatown with community organizers,33 tapping in with folks who speak the languages and hold the relationships, to connect directly with day laborers and small businesses in the surrounding areas, to offer resources and support, to learn where I can be useful and how. In the evening, I watch thorough and honest reporting from journalists and friends downtown, and bike to a favorite local taco stand where I never have to specify “vegetariano, con queso” because the taquero and his son already know what I like to eat, always joking around with me the second I bike up “haven’t see you in awhile!”

Chinga la migra. ICE out of LA. What gives me hope, personally, collectively, spiritually, is rooting in the materiality of physical place, on the LA river, in the streets, on our bikes, curbside with our taqueros and fruteros and street vendors, with the people who actually keep our streets safe. In the immediate wake of the fires, when all of us were still reading Mike Davis and speculating about LA’s predicted apocalyptic forms, I would read this poem out loud in the interstitial gaps between organizing.

I think I’ll stay on this

earthquake fault near this

still-active volcano in this

armed fortress facing a

dying ocean &

covered w/dirt

while the

streets burn up & the

rocks fly & pepper gas

lays us out

cause

that’s where my friends are,

you bastards, not that

you know what that means.34

Appropriately titled “Los Angeles, or the End of Assimilation,” a june 14th article traces the first week of june in los angeles to describe why the current movement to defend community members and neighbors from the raids takes its shape from the George Floyd Uprisings and Black Lives Matter movement rather than modeling itself after “earlier political movement towards assimilation and legalization that emerged during the pre-Global Financial Crisis.”

The bases are obvious: they are wherever immigrant workers congregate in the open, prey at any moment to DHS sweeps. The immediate task is to build zones of real sanctuary across the sprawling metropolis, to go to the workers and clearly present the burgeoning construction of a real peace, to fraternize and begin to dissolve the sociological differences that would compose this struggle as made up of allies on one side and the at-risk on the other.

Marking the spatial specificity of this movement, the first 72 hours in Los Angeles identify that:

These confrontations mark the reemergence of the conflictual spatial dynamic of the most interesting moments of the George Floyd Uprising (and the earlier Ferguson rebellion). Instead of the mostly empty downtown cores and its symbols of local political power, the raids opened a zone of conflict in the peripheral industrial and logistical archipelago that makes up the actual material reality of Los Angeles.35

Eastside Cafe. https://www.eastsidecafela.com/

Linda Quiquivix. “Palestine 1492: A Report Back.” Harvard Divinity School: Mar 14, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h1feUJu6P8A

Dionne Brand. A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging. Toronto: Vintage Canada. 2001.

V.I.J. Flint, "Christopher Columbus," Encyclopædia Britannica online, 5 September 2010. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Christopher-Columbus

Linda Quiquivix. 2025.

Naomi Klein, Astra Taylor. “The rise of end times fascism: The governing ideology of the far right has become a monstrous, supremacist survivalism. Our task is to build a movement strong enough to stop them.” The Guardian. 13 April 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2025/apr/13/end-times-fascism-far-right-trump-musk

Naomi Klein. “Fascism or Eco-Populism–Our Stark Choice.” UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy. 07 May 2025. https://challengeinequality.luskin.ucla.edu/naomi-klein/

Linda Quiquivix. Palestine 1492: A Report Back. Occupied Chumash Land: Wild Ox Books. 03 September 2024.

Linda Quiquivix. 2024.

Drafting Curbside. “Temporary Commitments: More Notes on Camp.” 29 August 2024. https://draftingcurbside.substack.com/p/temporary-commitments

Dirtbaby Farm. https://www.dirtbabyfarm.com/

Toni Morrison. “The Site of Memory.” 1987. https://bpb-us-e2.wpmucdn.com/websites.umass.edu/dist/f/16818/files/2013/03/Morrison_Site-of-Memory.pdf

https://www.instagram.com/p/CwieAaDP17t/

Zoie Matthew. “Northeast LA residents fight for their future.” KCRW. 14 September 2023. https://www.kcrw.com/news/shows/greater-la/surfing-northeast-la/black-walnut-trees

Drafting Curbside. “Infrastructural Improvisation: Choreographies for Spontaneous Movement.” 28 November 2024. https://draftingcurbside.substack.com/p/infrastructural-improvisation

https://www.tinaordunocalderon.com/my-passion.html

Julia Kloiber, Eric Siu, Joel Kwong. “Be Water - Insights into the Hong Kong Citizen Protest Movement.” About the Future in Times of Crisis, Zeitgeister: The Cultural Magazine of the Goethe-Institut. December 2020. https://www.goethe.de/prj/zei/en/art/22072105.html

https://inosanto.com/academy-info/curriculum/

EZLN. Them and Us, Part V. – The Sixth. January 2013. https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/01/27/them-and-us-v-the-sixth/

Dionne Brand. 2001. 62

Dionne Brand. 2001. 64

Naomi Klein. Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. 12 September 2023.

Erin Aubry Kaplan. “Why the Black Pope Matters–from New Orleans’ 7th Ward to South Los Angeles and Beyond: Reports that the new leader of the Catholic Church has mixed African ancestry offer a fascinating antidote to President Trump’s attacks on diversity in America.” Capital & Main. 21 May 2025. https://capitalandmain.com/why-the-black-pope-matters-from-new-orleans-7th-ward-to-south-los-angeles-and-beyond

All opinions are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my employer. LA Voice. https://www.lavoice.org/who-we-are/

EZLN. 2013.

June Jordan. “A short note to my very critical and well-beloved friends and comrades.” https://getlitanthology.org/poemdetail/62/

June Jordan. A Place of Rage. 1991.

Noel Brennan, Marissa Sulek, Sara Tenenbaum. “Thousands pack downtown Chicago for “Hands Off” protest against Trump administration in Daley Plaza.” CBS News Chicago. 5 April 2025. https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/hands-off-2025-april-5-protests-chicago-suburbs/

Huw Lemmey. “The Political Pop Art of Sister Corita Kent: In 1960s Los Angeles, a radical nun created artwork that turned the imagery of American capitalism on its head.” Tribune Mag. 13 August 2019. https://tribunemag.co.uk/2019/08/the-political-pop-art-of-sister-corita-kent

Gracie Hadland. “The bold spirit of Sister Corita Kent: Known as the ‘Rebel Nun’ in the 1960s, she produced colorful serigraphs that blended Pop art, spirituality, and activism. Decades later, her work continues to resonate.” 26 November 2024: Art Basel. https://www.artbasel.com/stories/sister-corita-kent-pop-artist-1960s-usa-college-bernardins-paris-2024?lang=en

Erica Chenoweth. Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press, 2021. 114-119

Amanda Del Cid Lugo. “Federal agents raided this Westlake Home Depot. Now it’s a place of resistance: Day laborers who fled in terror during federal raids now find solidarity at a grassroots support station outside the same Home Depot where their coworkers got detained.” Los Angeles Public Press. 17 June 2025. https://lapublicpress.org/2025/06/trump-raids-home-depot-immigration-defense/

Chinatown Community for Equitable Development. https://www.ccedla.org/

Diane Di Prima. “Revolutionary Letter #53: San Francisco Note.”

Victor Artola. “Los Angeles, or the End of Assimilation.” Ill Will. 14 June 2025. https://illwill.com/los-angeles

❤️🔥❤️🔥❤️🔥

sending this one to my blood family as part of an effort to explain to them wtf is going on in LA; love love love the Ariana Reines quote; God bless Paayme Paxaayt

I love so much of this. Saving it to read again and savour and remember. To me it speaks of hope and tenacity and those are much needed.